[contextly_auto_sidebar id=”fWCZOlqlcOkp84opgNwzY9TpfVFLSu9B”]

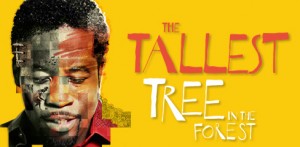

CAN an artist — in this case an actor and playwright — be a healer at the same time? Do the two roles reinforce each other, or do they pull in opposite directions? These were questions I got into in a new story on Daniel Beaty, a remarkable guy who is closing out the LA run of The Tallest Tree in the Forest, a play about the indescribable Paul Robeson.

While he’s been in Los Angeles, Beaty has also met with schoolkids to tell his story and show them the power of art to remake their lives. Here’s my opening:

On a recent sweltering day, the actor and writer Daniel Beaty spent six hours at a high school near Watts, showing the students how their pain could turn into poetry. A few hours later, and about 20 miles north, he walked onstage at the Mark Taper Forum to portray the singer Paul Robeson, Robeson’s wife, the Soviet filmmaker Sergei Eisenstein and 40 or so other characters in “The Tallest Tree in the Forest.” After his performance — Mr. Beaty has all the speaking roles in the show, which he also wrote — he met with a couple from Omaha to discuss bringing his youth workshops there. He finally finished his work around midnight.

I liked Daniel enormously, and mostly like his Robeson play. I have mixed/unresolved/complicated feelings about the issue of art’s role as therapy. Art can console; it can also (and must be able to) stir up and disturb as well. I’ll get into this over the months. I’ll point out that our culture — which includes both “art for art’s sake” and a centuries-old sense that the arts can be tools for healing — is every bit as confused as I am.

ALSO: It’s no secret that libraries, especially college and university libraries, are tossing out or storing their books — removing them, in a rush to digitalization, from spots where people might browse. A sharp story in Slate– pegged to events at Colby College in Maine — looks at this phenomenon much as I do.

The Bookies are quite right to want to save the stacks—but not just for the reasons they give, all of which could be dismissed as the sentimental drowning cries of Luddites. We must also save the stacks for another, more urgent reason altogether: Books, simply as props that happen also to be quite useful if you open them up, are the best—perhaps the only—bastions of contemplative intellectual space in the world.

The current cases for keeping the stacks—all of which I, as a raging bookish sentimentalist, happen to agree with—will, so long as digital technology advances accordingly, eventually no longer apply. Some studies show, for now, that online reading creates worse readers—that there is no replacement (yet) for the wonder of browsing.

Scribe Rebecc Schuman connects the issue to the larger transition of higher education to the corporate model; books, she says, are “the creators and the preservers of the contemplative space that every university needs if it’s not to turn fully into a strip mall with frats.”

Here’s the whole piece, “Save Our Stacks.”