[contextly_auto_sidebar id=”iZv7JeHqc41WMIllgv7eQnjxMkFtGil8″]

IF art and culture produce something besides money, what, exactly, is it? Who are the people who devote their lives to this stuff? And how have technological and economic shifts changed things over recent years? Those are questions I ponder often, and A.O. Scott addresses them in a perceptive and wide-ranging New York Times essay that avoids the temptation to come up with glib answers.

Artists, he writes, typically labor for their muse; they often talk about a higher calling.

Artists, he writes, typically labor for their muse; they often talk about a higher calling.

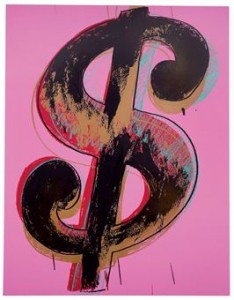

On the other hand, money is now an important measure — maybe the supreme measure — of artistic accomplishment. Box office grosses have long since become part of the everyday language of cinephilia, as moviegoers absorb the conventional wisdom, once confined mainly to accountants and trade papers, about which movies are breaking out, breaking even or falling short. Multimillion-dollar sales of paintings by hot new or revered old artists are front-page news. To be a mainstream rapper is to have sold a lot of recordings on which you boast about how much money you have made selling your recordings….

Everyone might be sure that sales are not the only criterion of success, but no one is quite certain what the others might be, or how, in our data-obsessed era, they might be measured.

Scott is right on here. Measures like box office yields used to be of interest only to people on the inside of the entertainment industry. But reporting on sales figures has increased along with the celebrity-industrial complex. In an age of Big Data, some journalists think they can explain or solve the problems of culture using numbers.

Scott’s other most important point is that most creative beings are neither the superstars we read about in magazines or the starving artists of 19th century myth. (Artists, let’s be clear, are having a harder time making a living, so starvation is not far for some, but the image has distorted things for more than a century now.)Most, instead, are in the middle. “The middle ranks — home to modestly selling writers, semi-popular bands, working actors, local museums and orchestras — are being squeezed out of existence.” I probably don’t have to point out to readers of ArtsJournal that “modestly selling” writers, musicians and the rest are often the most accomplished. (It was easier to see this in an age in which cultural criticism was stronger than bean-counting and horse-race coverage.)

The middle — that place where professionals do their work in conditions that are neither lavish nor improvised, for a reasonable living wage — is especially vulnerable to collapse because its existence has rarely been recognized in the first place. Nobody would argue against the idea that art has a social value, and yet almost nobody will assert that society therefore has an obligation to protect that value by acknowledging, and compensating, the labor of the people who produce it.

Scott concludes by arguing that the creative class and middle class can reconnect — an important point I explore in my book.

ALSO: When I write about subjects like the threat to reading, as I did recently, I typically hear from people berating me for being pessimistic: Reading is fine! Lighten up! Kids are reading YA books by the barrel-full, etc.

Here is a piece in the San Jose Mercury News that documents the decline. “Reading among children is on the decline,” the story begins, “with dramatically fewer teens and pre-adolescents reading even weekly, and many never picking up a book or magazine that’s not assigned, according to a report released Sunday.” As a teenager in the ’80s, I was hardly overwhelmed by fellow readers. But things have gotten worse since then. “In 1984, almost one-third of 17-year-olds read for fun almost every day; in 2012, the percentage had dropped to one-fifth. Those who never or hardly ever read for pleasure daily grew from about one-tenth to more than one-quarter.”

The biggest dilemma is for artists to find out what kind of artist they are striving to be. Some hard questions should be asked. Are you a Jazz musician that wants to be regarded in the same way Jay-Z is? Are you a painter that wants to be as famous as Kim Kardashian?

All too often, artists that follow a niche aesthetic live in cities that are lucrative markets for pop culture. Yes, some art exists within pop culture, but most art that has depth, longevity and resilience exists outside of mainstream pop culture.

So, with that in mind, one must quantify art that aims to be around for many years with a different set of principles. Is that artist trying to become a millionaire from playing art music? If so, good luck. Or, are you trying to change lives and minds through your art? If you choose the later, you can effect minds in important ways that might have an everlasting effect on young people. This is why it is important to teach younger people, in addition to performing. And, fusing the two can bring amazing results!

Are artist really starving, or is the idea of the starving artist a romanticized myth? Data from the Strategic National Arts Alumni Project challenges the myth, see here http://snaap.indiana.edu/pdf/SNAAP_2011_Report.pdf

I agree that as well as in the modern economy, the “middle” class artists built the foundation for the whole art scene. However, it is not a very inspiring image for the young artists that want to become something special, or the audiences that want to see something special. When it comes to art, it is always about something very special, or, better, exceptional. That is why the idea of “middle” class doesn’t work here.

Whether an artist wants to make millions through his art, or doesn’t care about money and wants to create a work of true depth, both reasons are good as the motivation to start creating. Artists do need the freedom of thought to start the process of creating and becoming.