[contextly_auto_sidebar id=”38DeNwZGJisbGbTELS20TK8CUWph1kUR”]

CULTURE and economics are connected, of course, in all kinds of ways, some simple, some complex. I often muse on the question of how rising income inequality relates to the arts, specifically the art market. A new story gets at some of it, using Capital in the Twenty-First Century, French economist Thomas Piketty’s bestseller, as its lens.

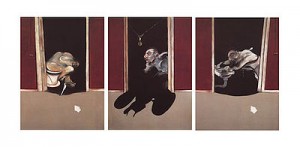

Piketty’s key insight is that things become extreme when returns on capital outstrip economic growth: Rich folks can simply invest their money and watch it surge, while those who work for their income fall behind. What does this have to do with the visual arts? A lot, says Scott Reyburn in the New York Times, who’s thinking in part of the high prices paid at auction for Freud, Bacon, Warhol and others.

Courtesy of the above-growth returns identified by Mr. Piketty, the rich are further increasing their wealth by buying art. Many millions have been made by a new breed of investor-collectors who buy Bacons, Warhols and Richters high, and sell even higher. Art by desirable investment-grade names makes the rich richer. And more and more wealthy individuals are now prepared to make bids of more than $100 million at auctions, while outside, beyond the shiny bubble of the art world, living standards in the rest of society stagnate or decline.

The story is historically informed, looking as far back as the Belle Epoque, and concludes that we’re returning to an era in which art is a plaything of the very rich. That leads to a winner-take-all market in which most (artists and collectors alike) are left out.

There are many more dimensions to this. Cornell economist Robert H. Frank has written how increased earnings at the top of the scale exert an impact on those in the middle, and art critic Jed Perl has writte n on the tragedy art becoming pure commodity. Others have written about what newly minted fortunes do to the cost of rent and real estate, especially in some of the cities associated with the creative class. Reyburn’s story takes a specific tack, and pursues it with clarity and intelligence.

n on the tragedy art becoming pure commodity. Others have written about what newly minted fortunes do to the cost of rent and real estate, especially in some of the cities associated with the creative class. Reyburn’s story takes a specific tack, and pursues it with clarity and intelligence.

ALSO: Think it’s just as bad everywhere? Well, income inequality is a problem in the entire post-industrial world, but it’s hit the U.S. especially harshly. New numbers from the Luxembourg Institute Study Database shows our middle class losing ground to Canada and much of Europe. The surveys show “that most American families are paying a steep price for high and rising income inequality” a story says. And here’s the lead: “The American middle class, long the most affluent in the world, has lost that distinction.” Not a surprise to many of us.

The New York Times also has a Salman Rushdie appreciation of Garcia Marquez, here.

FINALLY: One of my very favorite novelist is the Englishman David Mitchell, best known for his novel Cloud Atlas. I was lucky enough to speak to him for a piece when his last novel came out, and to meet him at a reading at Skylight Books. His next novel, The Bone Clocks, is due in September from Random House. EW has an image of the cover and a description of the plot. It begins:

Following a scalding row with her mother, fifteen-year-old Holly Sykes slams the door on her old life. But Holly is no typical teenage runaway: a sensitive child once contacted by voices she knew only as “the radio people,” Holly is a lightning rod for psychic phenomena. Now, as she wanders deeper into the English countryside, visions and coincidences reorder her reality until they assume the au

ra of a nightmare brought to life.

I’ve got a feeling I’m not the only reader eager to see this one. Mitchell, by the way, writes beautifully about adolescence.