[contextly_auto_sidebar id=”gUbWKQMto2pd9SNDW9DKGH0zVVcyuOMo”]

WHAT happened to political art? Has it seen a revival during a period in which inequality and related subjects are flaring? Does tackling a topical theme doom a work of art to becoming ephemeral? Will activist art ever again be as visible as it was during height of the AIDS crisis in the ’80s? We probably can’t answer all of that today, but a new project in Los Angeles, and a new appointment in New York, have me thinking about some of it.

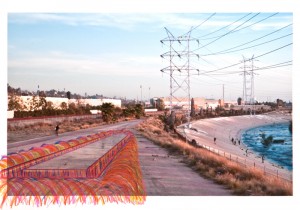

Over the last few weeks, along the banks of the Los Angeles River, artist Michael Parker has carved a full-scape replica of a 137-foot Egyptian obelisk; they’re calling it “The Unfinished.” One of the goals of the piece is to draw attention to the oft-neglected river and its relationship to the city. As Lewis MacAdams of Friends of the LA River put it:

This is the first artwork to really match the scale of the river. Most pieces have been swallowed up by

the river but “The Unfinished” matches the power of the river… This piece points the way between the artist and the remediation of the land. Parker is taking a piece of unused post-industrial land and using art to begin the process of remediation and healing.

One of the movers behind this — and I suspect, other intriguing projects in the near future — is Julia Meltzer, an artist and filmmaker who runs Clockshop, a group dedicated to political and public art. (Here is her piece on the obelisk.) The politics of this piece are more oblique than much of what the group does, though the fate of the river (and of public art, part of me wants to say) is political by definition. Meltzer herself is simply grateful the whole thing has gone so smoothly: “What is great is that it was made with the support from California State Parks and it was not costly, nor a bureaucratic headache,” she told me. “It was surprisingly smooth, easy and cheap. All of these qualities never seem to go hand in hand with public art.”

I first spoke to Meltzer years ago for a story about artists working to put art on billboards. (That idea has lately taken on a new wrinkle, thanks to a five-museum collaboration.) This was especially important, she argued, because fewer galleries and museums were making room for art with some kind of political edge. Has anything changed since then?

ALSO: One of the other sources for that billboards story was Tom Finkelpearl of the Queens Museum, who discussed the importance of public art. He’s now been appointed, by New York Mayor Bill de Blasio to head the city’s cultural affairs commission, which has a $156 million budget. According to the New York Times: “In his meetings with the mayor, Mr. Finkelpearl said, the two have mainly discussed shared principles, like making art available to every child citywide and improving arts education in public schools.

When we spoke back then, Finkelpearl told me:

The most successful pieces of public art have the ability to communicate across class lines. The words ‘public’ and ‘art’ have different class connotations.” The phrases “public restrooms, public transportation, public school” suggest working-class or lower-middle-class settings, he said. “And every survey about who consumes art shows that it’s a very upper-middle-class pursuit.

FINALLY: Hirschhorn curator Kerry Brougher will head back to LA this summer to head Academy Museum dedicated to movies and their history.

Alas, he will likely arrive too late to take in the Los Angeles Philharmonic’s Minimalist Jukebox Festival. I wish I could make it tonight to see wild Up’s performance.