[contextly_auto_sidebar id=”VwvlTpDOy3SsWouxN3cvJka5SISHA7pJ”]

ONE of the many ironies of our age is that as creative folk find it harder and harder to keep afloat, a whole world of books, workshops, and other sorts of guides to creativity continue to spring up. A sub-genre is the book which tells you about an artist’s or writer’s daily routine: How eccentric waking hours or diets or various kinds of outlandish behavior allow a certain genius to do what he or she does. The implication is that you too can take the royal road to creativity.

A new essay in Pacific Standard gently mocks the whole thing, pointing out that none of these geniuses’ daily habits has any resemblance to any others, and that they have virtually nothing to do with the brilliant output we know these figures for. Casey Cep writes:

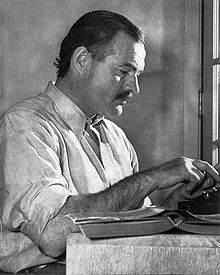

By which I mean Ernest Hemingway would still have written some of America’s greatest novels if he sat at his desk instead of standing and if he had worked while barefoot instead of while wearing oversized loafers. And if Don DeLillo wrote in the evening on an electric typewriter instead of in the morning on a manual typewriter, he would still be one of our great novelists. Just as Maya Angelou would still be one of our great poets if she showered in the morning instead of midday.

I got to see this myself not long ago when teaching a literary journalism seminar. Robert Boynton’s The New New Journalism features interviews with a wonderful array of scribes — Susan Orlean,  Michael Lewis, Gay Talese — most of whom have very distinctive-verging-on-neurotic working methods. But besides obsessiveness, there’s very little overlap. Over two decades interviewing poets, filmmakers, jazz musicians, and so on, that seems to be the rule: Creative artists find a routine that works for them, but it has to grow out of their needs and personality in a real way.

Michael Lewis, Gay Talese — most of whom have very distinctive-verging-on-neurotic working methods. But besides obsessiveness, there’s very little overlap. Over two decades interviewing poets, filmmakers, jazz musicians, and so on, that seems to be the rule: Creative artists find a routine that works for them, but it has to grow out of their needs and personality in a real way.

The shallow thinking around creativity explains some of the success of Jonah Lehrer, who made up some of his book on the subject.

ALSO: Social critic Thomas Frank is doing great work every Sunday in Salon. His latest is long and sweeping, and uses the McMansion, which first began its march across our suburbs in the ’80s, as a metaphor for how American life has changed since then. Here he is:

Today we call those changes “inequality,” and inequality is, obviously, the point of the McMansion. The suburban ideal of the 1950s, according to “The Organization Man,” was supposed to be “classlessness,” but the opposite ideal is the brick-to-the-head message of the dominant suburban form of today. The McMansion exists to separate and then celebrate the people who are wealthier than everybody else; this is the transcendent theme on which its crazy, discordant architectural features come harmonically together. This form of development wants nothing to do with the superficial community-mindedness of the postwar suburb, and the reason the giant house looks the way it does is to inform you of this. Have the security guard slam the gates, please, and the rest of the world be damned.

These changes have all kinds of effects on the lives of artists and other members of the creative class.

Also on Salon, the always-perceptive Laura Miller has a new piece, “Is reading antisocial,” on whether apps, sites and other digital innovations that “connect” readers make any sense. Isn’t reading by its nature solitary?

FINALLY: I like the idea of public art, especially in Los Angeles, a city that has devoted itself to the private over the public sphere for most of its history. But the way the 1% for the Arts program has worked out doesn’t inspire confidence. “A recent audit by City Controller Ron Galperin found that $7.5 million was languishing in the portion of the fund that is bankrolled by developers and earmarked for public art projects, cultural events and performances,” an LA Times editorial explains. “The money, accumulated over the last seven years, is just sitting there — ‘depriving the city of essential cultural enrichment,’ as the audit put it — waiting for the city’s Department of Cultural Affairs to commission art that it can be spent on.”

UPDATE: News just broke of Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s death at 87. One Hundred Years of Solitude may be my single favorite novel. Here’s an appreciation by the formidable Hector Tobar.

Evelyn Waugh’s “Scoop” got in early on this topic – mocking the kid reporter’s obsession with durable exercise-books and quill pens :))