[contextly_auto_sidebar id=”6RDST6owlrC0x8P60LIwnB5J7Z8Ftt9Q”]

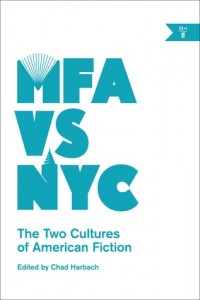

HOW does an aspiring novelist, poet, or essayist break into the business? What kind of ecosystem does he or she inhabit after getting established? Does grad school help? Among the best answers to those questions came from novelist Chad Harbach in his essay “MFA vs NYC,” and he’s expanded it into a provocative anthology that approaches the subject from a variety of angles.

The book is impossible to sum up completely — the writers assembled don’t all agree — but it’s both loads of fun and, I expect, a useful guide to young scribes.

MFA vs NYC: The Two Cultures of American Fiction, grows out of Harbach’s n+1 essay, reprinted on Slate.

Everyone knows this. But what’s remarked rarely if at all is the way that this balance has created, in effect, two literary cultures (or, more precisely, two literary fiction cultures) in the United States: one condensed in New York, the other spread across the diffuse network of provincial college towns that spans from Irvine, Calif., to Austin, Texas, to Ann Arbor, Mich., to Tallahassee, Fla. (with a kind of wormhole at the center, in Iowa City, into which one can step and reappear at the New Yorker offices on 42nd Street). The superficial differences between these two cultures can be summed up charticle-style: short stories vs. novels; Amy Hempel vs. Jonathan Franzen; library copies vs. galley copies; Poets & Writers vs. the New York Observer; Wonder Boys vs. The Devil Wears Prada; the Association of Writers and Writing Programs conference vs. the Frankfurt Book Fair; departmental parties vs. publishing parties; literary readings vs. publishing parties; staying home vs. publishing parties. But the differences also run deep. Each culture has its own canonical works and heroic figures; each has its own logic of social and professional advancement. Each affords its members certain aesthetic and personal freedoms while restricting others; each exerts its own subtle but powerful pressures on the work being produced.

His book takes off from this premise, with some championing programs (George Saunders, whose latest book of short stories I am reading now, as it happens), assaulting them ( the late, great David Foster Wallace, who was by all reports a very dedicated teacher at Pomona), criticizing with nuance (Elif Batuman), describing what it is like to teach at one (L.A. novelist Diana Wagman), interrogating the “dirty little secret” of anti-intellectualism and class relations they find themselves caught in (Fredric Jameson), and so on.

Roughly as many writers chronicle their breaking into the New York literary life, including n+1 co-founder Keith Gessen and Riverhead publicist Jynne Martin, whose piece is sharp and often hilarious.

What’s the “takeaway,” as the kids say? The economy of literary/academic culture is too complex to allow one. But every essay in this books brought me a little closer to understanding the business of writing in the 21st century.

ALSO: It may seem far from the subject at hand, but the surging inequality in the U.S. and elsewhere over the last four decades has had a powerful effect on writers and other creative types trying to make a living. One of the best chroniclers of this and related topics is Eduardo Porter of the New York Times: His new column argues that we’re only getting started. “What if inequality were to continue growing years or decades into the future?” he asks. “Say the richest 1 percent of the population amassed a quarter of the nation’s income, up from about a fifth today. What about half?”

FINALLY: I wish I’d been able to attend a Zocalo Public Square event, moderated by my friend Joe Mathews, that considered the past and future of newspapers in Los Angeles. The panel included Orange County Register owner Aaron Kushner, who is expanding into LA. Kushner ha gone against the grain by dedicating himself to print in the age of the Internet. Kevin Roderick of LA Observed assesses the discussion here.