[contextly_auto_sidebar id=”fCuLD2IqdN12lY1YuMoXVQLgOFYy7oc1″]

Since the exact date is ambiguous — he was born sometime in late March of 1685 — I’ve decided to declare today Bach’s birthday. That gives me great pleasure; Bach was the first composer to hit me hard, and is still my favorite. It also frightens me, because of the way Bach’s music is typically used in films to signify something frightening, decadent, hyper-rational, fascist, and so on.

That was the subject of a story I wrote a few years back, based on the work of musicologist Kristi Brown. I begin by talking about the was classical music typically represents civilization, “class,” and gentility when it plays in television or movies. But Bach often functions differently.

That was the subject of a story I wrote a few years back, based on the work of musicologist Kristi Brown. I begin by talking about the was classical music typically represents civilization, “class,” and gentility when it plays in television or movies. But Bach often functions differently.

“I became interested in the films that were violent and that had a certain kind of protagonist,” says Brown, 39, a daughter of the Central Valley who’s surely among the nation’s perkiest musicologists. These protagonists, she says, tend toward geniuses driven mad by technology and rationalism, or exemplars of a decadent European culture who’ve had the morality burned out of them — from Benson, the crazed computer scientist in “The Terminal Man” (1974), to the erudite and malevolent Hannibal Lecter of “The Silence of the Lambs” (1991) and “Hannibal” (2001). Both men gruesomely kill, she points out, while playing the same piece, the 25th of Bach’s “Goldberg Variations.”

Why does this happen? We bounce around some explanations in the piece.

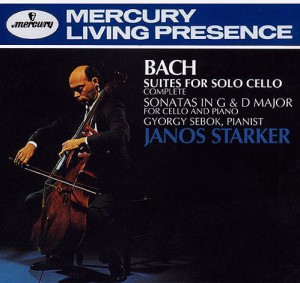

This all aside, I want to un-ironically praise Bach’s music for a moment. I was in my mid-20s, and a dedicated rock and jazz fan, when classical music really got through to me. The classical critic at the paper I had just joined, the New London (Conn.) Day, played me Gould’s Well-Tempered Clavier, and Janos Starker’s 1960s recordings of the Cello Suites. My ears have simply never been the same since. Milton Moore, my old friend, has a piece on Bach today I urge readers to check out here.

ALSO: The Japanese architect Shigeru Ban has just won the Pritzker Prize, architecture’s most important award. The fact that Japanese designers have won three of the last five Pritzker’s reinforces something the Paris-born, Los Angeles-based architect Olivier Touraine told me — that the lack of public investing in architecture in the US meant that foreign architects, especially Japanese, would gradually eclipse Americans when it came to important projects. (My book has a chapter on where architecture is headed; Touraine is an important source for that chapter.)

Here is a typically smart and wide-ranging essay on Ban’s award by my old LA Times colleague Christopher Hawthorne: “His belief in architecture as a political and humanitarian art as much as an aesthetic one separates his work from the sleek, precisely wrought high-tech buildings by last year’s Pritzker winner, Toyo Ito, and the white-on-white, nearly weightless minimalism of Kazuyo Sejima and Ryue Nishizawa, the 2010 honorees.”

FINALLY: Smart/ frightening David Carr piece in NYTimes about journalism’s drift toward click-bait and chasing traffic. This reinforces my sense that the erosion of the traditional “wall” separating the editorial/news-gathering side of a publication from its business operations and revenue generating will have baleful consequences.The demise of the subscription model is deadly, too: As with a theater company or record label or cable subscription, you need some way for the popular stuff to pay for the important stuff (sometimes, of course, those categories overlap) or the whole thing becomes a race to the bottom.

Bach is all things to all people, hence the Bach abuse on film scores. Someone smarter than I once wrote that when, say, Tchaikovsky is sad, his music tells you how sad he is. When Bach does sadness, the music itself stands apart from him. Well done, my friend! Here’s to Bach, branch whiskey and blogging!