[contextly_auto_sidebar id=”5JaPY4EuOTgKJQzRDmJq9iKTEWZtZtT7″]

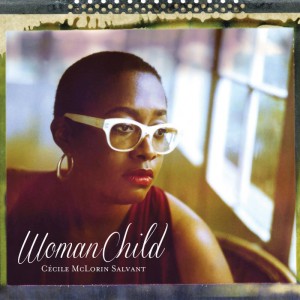

SHE’s not just my favorite new jazz singer in many moons, but someone who points the way forward for the music. That’s the sense I’ve gotten from the young, classically trained vocalist Cecile McLorin Salvant, who played the other night at Catalina’s and whose album, WomanChild, is a knockout.

Part of what I like about her is the way she takes jazz standards and makes them her own. Like Cassandra Wilson, she’s found a way to be contemporary and tap into jazz tradition at once. “One of the finest sleights of hand in music is to write a song that sounds like a long-lost standard,” Chris Barton wrote in his review of her show. “Equally impressive, however, is the rare ability to perform a classic song and make it sound utterly new.”

The issue of song selection — as central to a repertory-driven art like jazz in a way that it’s not for, say, rock ‘n’ roll, which, since the Beatles, has been about original songwriting — has been talked about for years now. But it all became more pressing lately, with the emergence of several high-profile artists who reject or ignore the tradition of Porter, the Gershwins and Jerome Kern — or even the related lineage of songs by jazz musicians, such as Duke Ellington and Billy Strayhorn’s “Lush Life” or Thelonious Monk’s “Round Midnight.”…

The issue has symbolic meaning, because with the dropping out of a shared body of songs, jazz has lost not only its common language – for decades, musicians getting together for the first time could count on each other knowing the changes to “I Got Rhythm” or hundreds of other songs. It’s also lost its emotional connection to its mid-century heyday, when high-quality, greater visibility and a solid canon reigned: Despite all of the warring schools, each of which had its pet repertoire, many of the musicians played the same songs, even if different teams rendered them differently.

My point was that standards need to be part of the mix, but they can’t be rendered in a static way. McLorin Salvant, who covers “I Didn’t Know What Time It Was,” “Jitterbug Waltz,” and “What A Little Moonlight Can Do” — and played more the other night — clearly knows this, and exemplifies it beautifully.

ALSO: A filmmaker in Pittsburgh has chronicled the struggles of local artists who’ve fallen ill without health insurance, and her documentary, Healthy Artists: The Movie has started to get attention. A New York Times story — which called Julie Sokolow “A Crusader on What Ails Artists” — describes it this way:

There was Eanna Holton, who makes horror masks and props and recalled spending the last five years paying off a $10,000 surgery bill for her toddler. China Horrell, her co-worker, had a pulmonary embolism that cost more than $100,000 to treat. And Daniel McCloskey, a comic-book artist, told of being uninsured when he smashed his teeth in a bicycle accident last year, at a cost of more than $22,000.

The story provides some video excerpts from the film as well. A 2013 survey showed that 43 percent of artists lacked health coverage.

FINALLY: One of my longstanding interests is what makes fiction from California and Los Angeles, different from writing elsewhere in the world. (I co-edited an anthology on the subject, The Misread City, about a decade ago.) So I’m pleased to appear on Friday as part of the conference Writing From California: Tales From Two Cities. This takes place at LA’s beautiful Central Library, is sponsored by USC and the Huntington, and is entirely free.

I’ll be running a panel called “Creating Alternate Universes,” which will look at the way West Coast writers break from the traditions of literary “realism.” The writers Edan Lepucki (California) and Charles Yu (How to Live Safely in a Science Fictional Universe) will be there with me, and Aimee Bender (originally scheduled to appear) has written a bit on the topic, which I’ll discuss. In any case, the conference runs from Thursday to Saturday will also consider Joan Didion, Thomas Pynchon, Raymond Chandler, and others. Don’t miss it.

As we all know, genres like jazz and the blues were born out of incredible human suffering. In some ways, jazz is a kind of soundtrack for a history that moves from misery and degradation toward freedom and dignity. When Billie Holiday sang, one could hear almost immediately something in the music that tells you she has been to hell and back. One hears a struggle toward a sense of human dignity. Or at least that’s what I hear. There’s much of the same in Ella Fitzgerald’s voice, though her life might have involved less suffering than Billy’s. How is so much history conveyed through the tone of a voice, or the nuance of a phrase?

Louis Armstrong was also a man of his times. Some accuse him of being too conciliatory, of lacking the anger he would have been justified in having. When I listen to his music I seem to hear conflicting ironies, one that is too conciliatory and another that has the incredible courage to embrace joy in spite of unspeakable adversity. By contrast, it seems like one can hear a lot more anger and pride in the music of Miles Davis, but with a deep sense of frustration and a struggle to feel hope that becomes almost separatist, as if he were speaking for a new birth of consciousness.

And then the history comes to the present day with artists like Cecile or Wynton Marsalis. Even if there is still so much to be done against racism and its legacy in America, their lives have been so much better and you can hear it in their music. The sense of Lady Day’s journey to hell and back isn’t so strong. There’s so much more confidence and dignity. The sense of anger is more remote. The place of extreme isolation is more distant. There’s more hope. Of course, I wonder if these perceptions are merely projections from a historical narrative, or if they really are something truly contained in the music itself?

I think its in the music and that this seems to be creating a fairly big change in what jazz is. It’s as if the sense of celebration it always had has become more complete. Maybe this is why people like Cecile can bring a whole new style to old standards or create new songs that seem to have a historical meaning that gives them a sense of being old classics. A history, a sense of relief, a new sense of hope and inclusion, and a new kind of dignity fills the sounds they create. Music isn’t just sound. It’s an idea, a worldview, a way of being. Those are the things that give music its meaning. They are what allow it to be constantly reinvented.