[contextly_auto_sidebar id=”o511ReiogmTCk65Pr1jtarJdMtJ8q5at”]

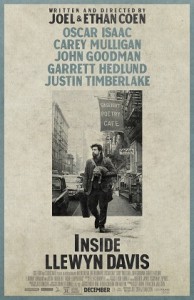

IN the weeks since I’ve seen it, I’ve gone back and forth on the movie Inside Llewyn Davis. The film was beautifully shot and well acted, I love the way some of the scenes of Greenwich Village make it look like the characters are inside the cover of Dylan’s Freewheelin’ , and so on.

But I also couldn’t help thinking that for all the film’s virtues, it completely missed capturing the early-‘60s folk scene in which it was set. Compare it to O Brother Where Art Thou, a movie much less explicitly about music, and the songs are a lot less fun and less fully realized. Instead of convening the top musicians in the new-acoustic scene, as they did for the earlier film, the Coen Brothers mostly used the actors in the film and ensuing recording. (As lovely as some of the soundtrack is, the song I hear talked about the most is a goofy novelty number.)

And Llewyn Davis has no politics, no sense of the communal, and virtually no joy – three elements that powered the folk movement.

The peerless cultural historian Leo Braudy digs deeper into these doubts in a new piece on Pete Seeger. The essay begins with a smart assessment of Seeger’s life and work during the chilliest of the Cold War, but Braudy then turns to contrasts the recently deceased folkie with the Coens’ character:

Thinking about Seeger’s career in the wake of his death makes me wonder about Inside Llewyn Davis, the recent film by Joel and Ethan Coen that purports to chronicle both the New York folk scene of the 1950s and the career of one singer, said to be inspired by the folksinger Dave Van Ronk. It was an age of real musical ferment in folk, in jazz, and in rock and roll. But aside from the resolute darkness of the storyline — my wife has taken to calling the Coens the Grim Brothers — nothing of this energy, and especially nothing of the optimism and the joy characteristic of Pete Seeger’s kind of folk singing, is present in the film. Instead it follows the rapidly disintegrating career of Llewyn, a solitary, pugnacious, injustice-collecting folksinger whose general air of repellent narcissism is softened only when he sings, often beautifully, his own songs. Otherwise he is total pain in the ass, to his friends, his sister, and everyone else around him.

Braudy’s whole piece is worth reading (as is his history of fame, The Frenzy of Renown, and the USC scholar has a new memoir, Trying to be Cool: Growing Up in the 1950s, that I’m eager to read.)

I’ll conclude with what may seem to be contradictory thoughts: First, the Village folk scene turns out to be an imperfect match for the Coens’ dark gifts.

Second, Inside Llewyn Davis was, whatever its faults, far closer than most movies to the real life an artist. The fact that Llewyn, despite his talents and dedication, struggles, struggles again, and does not triumph in the end, makes it a very rare honest tale about life as a creative being. And for this it becomes a valuable document.

I get into some of these issues in more depth in an upcoming story on recent film.

Interestingly, a latter-day folk singer, Richard Buckner, is touring living rooms across the country this month and through the spring for small concerts. He’s someone whose work I’ve loved for more than a decade, and I’m glad to see him finding new ways to keep his high-integrity career going. He’s in California this month. Let’s just hope he doesn’t let the cat out in the morning.

I haven’t seen the Coen Bros. film yet (being allergic to yakking idiots seated around me), but just last night i watched a Netflix streamer documentary called “Greenwich Village: Music That Defined a Generation,” which had some very good moments and insights. It focuses very much on the shared experience of the folkies and lefties there, had some very good performance clips and absolutely cast Pete Seeger as the ecstatic godhead.

Many people who were so important back then, like Buffy St. Marie, Eric Anderson and Fred Neil, are brought back vividly, but some key people – most notably Dave Van Ronk – get shorted (copyright issues, perhaps).

I definitely recommend it.

Thanks for zeroing in on what was (to me) ILD’s true achievement: its unsparing representation of “the real life of an artist.” That was why I liked it so much. Plus, no moral uplift whatsoever!

I do wonder if the film was meant (or should be expected) to provide a comprehensive account of the milieu and era. Perhaps that’s too much to ask of an imaginative work.

In any case, many of us who lived through the sixties from folk to mod to flower-power remain somewhat ambivalent about how joyful the period was, depending on our our experiences and memories, of course,