[contextly_auto_sidebar id=”MXOnux5h60TpQeeW1oA2Sr2osSWsecFp”]

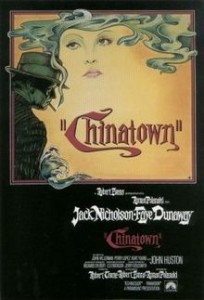

SEVERAL of the big, prestigious films of recent months look at the Wall Street crash, corrosive greed, and economic insecurity. But how substantially do they engage with these topics? Is there a Chinatown or Network or The Wire — narratives that wage a larger social critique — in the bunch? I get into these questions in my new Salon story, with help from some perceptive scholars and scribes.

Here’s where I go a few paragraphs into the piece.

Take a look at the movies released last year – the New York Times reviewed almost 900 — and you’ll see glimpses of these overlapping crises. “The Wolf of Wall Street” and “The Great Gatsby,” while set in the past, look at charismatic con men of the kind that seem all too familiar these days. “Inside Llewyn Davis” focuses on a musician – part of a Greenwich Village scene built on social protest — who’s living the kind of limbo many Americans are experiencing today. And “Blue Jasmine” concentrates on the disenfranchised wife of a Bernie Madoff figure who gambled with other people’s livelihoods, and lived in luxury until the whole system blew apart.

Economic issues have been central to many of our lives over the last few years, and they’re especially crucial to the lives of the creative class: Artists, journalists, writers and musicians have seen their fortunes scrambled.

One of my favorite things about this piece was the chance it gave me to discuss these topics with some of the sharpest people I know — film historians Leo Braudy (USC) and Jonathan Kuntz (UCLA) and journalists Peter Biskind, Manohla Dargis and Gene Seymour.

I look especially forward to comments on this one.

ALSO: One film I’m looking forward to, which has little to do with these topics, is God Help the Girl, by Belle & Sebastian frontman Stuart Murdoch. (I’ve been besotted with the Glasgow band since the ’90s.) The film goes up at the Berlin International Film Festival on Friday; am hoping it gets US distribution before too long.

ALSO: On the economics of culture, Moby has written an eloquent piece about leaving New York — once the capital of culture, now “the capital of money” — for the Guardian. A creative life requires the possibility of failure; he finds that goes down better in Los Angeles. “In New York, you can be easily overwhelmed by how much success everyone else seems to be having, whereas in LA, everybody publicly fails at some point – even the most successful people… Experimentation and a grudging familiarity with occasional failure are part of LA’s ethos.”

Your article in Slate is well done and very interesting. What a rich summary of political art in cinema. Thank you. I also like your explanations for why contemporary American culture often seems to lack substantial political dimensions – a problem that extends to the performing arts as well.

I think an additional reason might be the scarcity of what was once termed “public intellectuals.” In the middle of the 20th century, American culture was receptive to intellectual generalists such as those centered around the _Partisan Review_. These writers included luminaries such as Edmund Wilson, Paul Goodman, Harold Rosenberg, Lionel Trilling and Mary McCarthy. It has been suggested that Susan Sontag was the last writer of that tradition. These generalists shared a desire to exhibit intellectual range. They found a way to pay attention to specific intellectual topics and yet comment on the larger cultural context in which those topics appeared.

As a result, we no longer have as many politically oriented cultural journals. (The few exceptions seem to be mostly those involved almost exclusively with identity politics.) This has further narrowed our perspectives, and weakened political sophistication in the arts and arts criticism. The ideologies, reporting, analysis, and terminology of public intellectuals and politically oriented cultural journals once helped artists clearly define and portray the social realities of our time. Without them the presence and sophistication of political art has been weakened.

Another result has been a lack of understanding about the economic concepts of neoliberalism, which has been the driving force behind the economic shifts, imbalances, and industrial lapse of America over the last 40 years.

Another general problem that creates a lack of political art is that we live in a culture of simulation, as Jean Baudrillard has famously observed. The mediation of reality through the mass media creates a world where most everything seems to be a simulation instead of something real. After a century of Hollywood’s dreamland, it is now very difficult to associate the cinema with reality, much less social reality. Those who lived in NYC in the 70s (like me) might know the film portrays a very real world, but in the gentrified Manhattan of today, it seems like a fantasy. (“Serpico” is another good film about the social realities of NYC during the 70s.)

I think this might be why television seems to be superseding cinema in some ways. Television is generally an even bigger lie than the movies, but when it tries to tell the truth with programs like “The Wire” its smallness seems more true to life. In a world of outsized and over-dramatized simulacra, we can only see the truth when it is under played. Or only when it seems to appear as an unintentional and ironic side effect of the simulated stories we are accustomed to.

And of course, the lack of political art in the USA might also stem from the country’s narrow political spectrum. The social and cultural climate in Europe is far more politically diverse than in the States. Every country has a wide range of parliamentary parties, as opposed to the limited and often overlapping perspectives of America ’s two party system.

One cannot think of composers like Luigi Nono or Hans Werner Henze without considering their deep questioning of the structures of politics, power and privilege in Western societies. Americans, on the other hand, are almost conditioned to believe that such questions represent a form of class warfare that is somehow tacky or inappropriate.

This helps explain why a politically engaged composer like Frederic Anthony Rzewski spent so much of his life in Europe. To put it perhaps a little too simply, his thought would not have fit in the States and he probably would have been marginalized. This negative attitude toward political artists might also explain why a composer like Conlin Nancarrow spent his life in Mexico after his persecution by HUAC. We often consider events such as these as insignificant, but over time this atmosphere of special contempt for political art and artists has probably had a significant effect on suppressing political art.

Another factor whose significance is probably still underestimated was the CIA’s covert program of arts funding through its front organization called The Congress for Cultural Freedom. They channeled millions in funding to help abstract expression become the dominate postwar aesthetic in the arts exactly because it was non-political.

More recently, we have seen a related phenomenon in the suppression of arts funding hidden behind surface events like the Mapplethorpe controversy. The general ethos seems to be that artists are not to be trusted, exactly because of their possible political and social inclinations, while in Europe, even the most political artists are often esteemed and supported by extensive public funding.

When one considers the massive social problems in the States, like racism, urban squalor, poverty, and militarism, the country’s relative lack of politically oriented artists becomes very notable. And it is even more striking if we compare this barren atmosphere to the politically engaged atmosphere of the arts in America during the 1930s before it was ravaged by the political suppression of the 50s, or its brief reemergence in the 60s.

The lack of political art is also related to America ’s rather radical and isolated system of arts funding, where almost all financial support comes from the wealthy. It is the only country in the world with such a system. All other developed countries publicly fund the arts.

Anyway, if we ask what an American artist is, it is someone who is probably non-political, someone who is now part of an artistic tradition that has been politically limited for so long that it no longer has a vital history or tradition upon which to build political art. This has left American culture with a relatively limited intellectual and technical capacity to create political art, and a limited public for it when they do.

Sorry, I know this is inappropriately long, but this is a big and complicated topic that isn’t discussed so often.

I left out the name of the film from the 70s I was referring to: Taxi Driver.

Superb comment by Mr. Osborne. Two issues he brings up are especially important to me. First, the tradition of the public intellectual, in the Partisan Review mold, is very close to my heart. I admire all the writers he mentions, with Leslie Fiedler being an important early inspiration.

Second, my research into the creative class brought me deeper than I expected to neoliberalism, which is not just an economic vision, but a value system, a cultural stance, and much else.

More, over time, on both of these topics.