[contextly_auto_sidebar id=”K7jgN35EvK3IGRvlOHBgaw79mmby3Zkj”]

ARTISTS, writers and musicians have been considered “eccentric” for hundreds of years, at least since the Renaissance and perhaps as long ago as the prehistoric age of the shaman. What’s behind it? Is it just a narrow-minded stereotype? Are crazy artists better than sane, conventional ones?

Whether artists really are eccentric, or have to be to produce bold and original work, the rest of us seem to perceive their work as better the more personally unconventional they are. A story in Hyperallergic documents this.

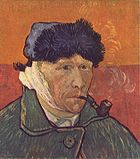

Psychologists Wijnand Adriaan Peter Van Tilburg, from the University of Southampton, and Eric Raymond Igou, from the University of Limerick, Castletroy, Ireland, have recently published an article titled “From Van Gogh to Lady Gaga: Artist eccentricity increases perceived artistic skill and art appreciation” in the European Journal of Social Psychology. In the paper, obtained by Hyperallergic, they detail a series of studies they conducted to measure the correlation between perceived eccentricity and artistic talent.

They used Van Gogh’s Sunflowers and his ear-slashing behavior to get at the way people respond to artistic works. The bottom line: The crazier the better, as long as it seems “authentic” (a fraught category in the arts.)

A fine NPR report on the study is here.

ALSO: Among my deepest commitments over the years has been to the music of the Beatles. John Lennon became, when I was six or seven, my first cultural hero; I recall the day he died (when I was in sixth grade) all too clearly. But the recent Beatles anniversary onslaught is just one of the reasons I’m responding to a wonderful Harper’s essay on the band, their impact, and perhaps their exhaustion.

James Marcus has as fierce a passion for the band as I do. But he writes:

Is it finally time to let go of the Beatles? I feel strange even posing the question, having been born on the cusp of the glorious Sixties and formed, to an astonishing degree, by John, Paul, George, and Ringo. Oh, there was plenty of other stuff going on — Vietnam, LSD, black power, feminism, and the so-called sexual revolution, which Philip Larkin famously pegged to the 1963 release of Please Please Me. But what got etched into my brain, as if it were the surface of one of those malleable, lacquer-coated acetates, was that music. My father, a Toscanini fanatic who had actually sold his digestive juices as a medical student to pay for his first turntable, bought all the early records. When my parents had dinner guests, he would play them “Ask Me Why” to prove that the Beatles weren’t simply long-haired louts but could sing in tune and write something with those jazzy, sophisticated sevenths.

The essay is too personal and complex to sum up quickly — it swings from skepticism to fanboy love and back. The Jonathan Lethem reference is one of many fresh and lively things about it. I don’t agree with all or even most of it, but urge everyone to read it.

FINALLY: What is improvisation? What do music and language have in common? These questions and several others are explored in an Atlantic story:

The idea that jazz can be a kind of conversation has long been an area of interest for Charles Limb, an otolaryngological surgeon at Johns Hopkins. So Limb, a musician himself, decided to map what was happening in the brains of musicians as they played… What researchers found: The brains of jazz musicians who are engaged with other musicians in spontaneous improvisation show robust activation in the same brain areas traditionally associated with spoken language and syntax. In other words, improvisational jazz conversations “take root in the brain as a language,” Limb said.

There’s more to say about all of this. But rushing off to moderate a panel on California fiction. I welcome comments on all of this and wish everyone a good weekend.

Oddly enough, some of my favorite composers were the least eccentric: Haydn, Strauss (a fine bourgeoise gentleman), Prokofiev. There is a large disconnect between perception and reality, and for the last generation or two of painters and visual, the marketing of them relied on a catchy storyline.

Your thoughts on Charles Limb get at the same thing Amiri Baraka (Le Roi Jones) theorizes brilliantly, and points out repeatedly (albeit in more “poetic” language) in his various books on jazz.

I think it’s a very useful point, with deep implications for all forms of language as both communication, expression and creation/transformation.

In poetry, by contrast, the sound of words are said to be musical.

To connect these thoughts on jazz to the thoughts about the eccentric artist–

It does seem that it is precisely the collective improvisations that make each individual soloist LESS eccentric.

Milton makes a good point. In the case of poets, for instance, I loved as a young man the myth of romantic or self-detructive poets (Rilke, the Beats, etc) but many days I would rather read a “straight” figure like Richard WIlbur, Donald Justice or Elizabeth Bishop. (The term “straight,” of course, does not apply in every sense to her.)

Re. Chris’s point about the musicality of poetry, to the ancient Greeks, music and theater were connected and virtually all literary language was musical and often, I think, accompanied by a lyre or pipe playing. Edmund Wilson has a great essay about how the Romans separated language from poetry, and the rest of us have paid a price for it.