[contextly_auto_sidebar id=”iQQVe5TAzEEnpCsYlIIqaek1CQTiG9Gn”]

WELL, I feel like the vaudeville announcer lingering onstage because the dancing girls are late: The piece I intended to launch this blog with turns out to be waiting until the weekend. But I’m quite intrigued by this essay on creativity, work and careers in the arts, which appears in my favorite newish magazine, Pacific Standard. It asks, “Should You Really Make Your Passion Your Job?” These subjects are central to reporting and research I’ve been doing over the last couple of years on the creative class.

Author Kyle Chayka starts this way:

In our current start up-obsessed moment, aspiring to have a job that already exists seems almost unfashionable. The true goal of meaningful employment, or so the aspirational entrepreneurial culture would have it, is to create your own job, distilling your utmost passions into a career that is enriching in both the soul and the wallet. Fulfillment! Salary! Material consumption! These are the inherent promises of doing what you love, or DWYL, a slogan-turned-ideology that recently received a smart takedown by Miya Tokumitsu in the leftist Jacobin magazine.

And as the Brooklyn-based Chayka concedes, for all the self-determining energy that artists and people who work with them receive, the life ain’t easy, especially these days:

Conflating creative passion and capital, however, can be hazardous, as the economic situation of the arts in the United States in particular suggests… A 2012 survey found that those who studied visual and performing arts in college averaged a starting salary of just $33,800 (compared to $41,900 for history majors, and more than $70,000 for those in finance). “The arts industry, at all levels, is subsidized not just by the labor of artists, but by their quality of life,” wrote Paddy Johnson, a well-known art blogger, in a New York Times op-ed. The fact that art-making is a passion doesn’t necessarily make it profitable and it doesn’t mean that it’s a job.

Chayka was once a staff art critic, and realized, eventually that this was, for him, better a hobby than a job. He goes into some detail about the issue and I don’t want to steal the dude’s thunder. (I also recommend the sharper-edged Jacobin article.) Here’s a key line, though:

Art and creativity don’t need to be monetized—in fact, presuming the need to do so degrades their potential to be a source of joy for the creator, as any artist who has to follow the demands of an external market rather than their own sensibilities knows.

I’ll point out what may be an obvious tension here: Many of us who work in culture at some level have struggled, over the last few years, with the new world that announced itself in 2008 but had been building for years, maybe decades previous. Income polarization, a casino economy, cuts to arts education and funding for culture, declining newspaper readership, the closing of bookstores and record stores, on and on.

But to those of us still do this – who hand-sell books or play saxophone or write about art for a living – does this stuff provide any less sustenance and meaning than it ever did? Ask me in 10 years, I guess. But just because most of the world assesses things based on income or Big Data doesn’t mean that we have to.

This may come as a shock in a technocratic, neoliberal world, but not everything can be quantified.

Folks? How does it look to you out there?

Update: President Obama has weighed into the issue by dissing (sort of) “art history degrees,” here.

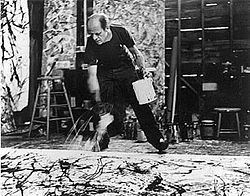

(Pollock photo by Hans Namuth)

“Does this stuff provide any less sustenance and meaning than it ever did?” The bottom line is that bills need to be paid. And while it can be romantic to live with minimal comforts while one is fresh out of college and full of optimism, the charm eventually fades.

My husband (pianist/composer/game developer) and I (choreographer/director) have both become happier and more relaxed since we each found dayjobs just over a year ago. We are fortunate that the hours are sufficeint but not overwhelming and the pay is stable, which has given us the freedom to pursue our artistic activities during the off-hours. In the end, these artistic pursuits bring us more satisfaction than before because we are not stressed about paying the rent every month. It has also allowed us to be more selective about the projects we take on: we can choose to participate in something because the work itself will be truly fulfilling, versus taking every odd accompaniment or assistant directing gig that comes along simply because we need the cash.

And through all of this my commitment to and faith in my art has become stronger: I continue this work because it is important to me, and within in myself, I now know the validity of my work. I am no longer desparately seeking outside assurance that a life in the arts is justified.