THIS year — soon drawing to a close — has gotten me thinking about the American songbook in a major way. Part of this is because of the publication of Ted Gioia’s wonderful The Jazz Standards — which has shown up on a number of year’s best lists, and through which I have whiled away many hours.

Another is the notorious Atlantic article, “The End of Jazz,” which is both a review of the book and a larger essay — intelligently argued, albeit not entirely convincing, I don’t think — about how the disconnection between jazz and the songbook has left them both dead.

The third, perhaps, is my own progress (if you heard me play, you’d know that this is probably the wrong word) as an amateur jazz guitarist, learning various numbers such as “All the Things You Are,” “Autumn Leaves,” “Chitlins Con Carne,” “Goodbye Pork Pie Hat,” “Blue Bossa,” and so on. I’ve been struck by how inventive, ingenious and musically bottomless these great songs, whether by Jerome Kern or Charles Mingus, remain. How far can you stretch ’em before they break?

And how does the shrinking of the jazz audience connect to my ideas about the crisis of the creative class?

For my latest piece for Salon, I’ve looked at some of the issues, and crossed them with a look back at jazz over the last year or so. My understanding of some of this mix of good and bad was bolstered by another very fine new book, Marc Myers’ social history Why Jazz Happened.

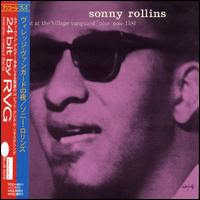

I spoke to Myers, Sonny Rollins, jazz scribe Gary Giddins, head of Nonesuch Records Bob Hurwitz, and others. The question of how jazz can thrive in the future is important to me and I hope I’ve taken a step into understanding it.

Happy holidays to my readers from The Misread City.

.jpg)

Good article. Mehldau has been somewhat successful in adapting newer tunes. Hard to think of many other examples. Most recent popular music is pretty threadbare melodically.

Good article, but one quibble:

Time Out was the album, not a single. Perhaps you’re referring to “Take Five” as the single.

Excellent piece, Scott.

As a working jazz pianist rooted in older traditions, from stride piano on, I have long been lamented jazz’s fixation- literally, a fixation -with standards. I love standards. But they weren’t standards when the people who made them so played them. They were pop songs. They were part of the new musical fabric.

Today, however, the only fabric of which standards are a part is the frayed Linus security-blanket of antique comfort through historical repetition.

To my mind, this applies not only to the repertoire jazzers choose, but to musical forms and harmonies as well. Change is overdue.

I’ve advocated a re-engagement by jazz with its pop roots. One sees shoots of such engagement in some of the jam bands’ work, but little of it in the prevailing jazz soundscape.

On my ‘Blue Modules’ recording, my 8th (to be released in January), I try to put into practice the principles I’ve been espousing. Whether I succeed is for others to judge. But I am gratified to have just learned that my guitarist colleague on ‘Blue Modules’, Donna Grantis, will not be able to join me for my CD release shows, as she has just been hired to be part of Prince’s band. If that isn’t pop, I don’t know what is.

I don’t entirely want this to be public because it’s late and I’ll probably say something offensive. So I sent in a facebook message. But in case you didn’t see it, here’s my 2am $.02.

The American songbook did not kill jazz. If jazz artists want more listeners, the answer is not to stop performing the pop standards of the 1930s, unless they are going to write new standards that are still pop songs. The new jazz being written is the heady, academic stuff that only other jazz musicians can relate to. I love Esperanza, but I include her stuff in that assessment. And the idea of having jazz artists cover current pop is cute, but it’s not going to work unless they retain the parts of the song that make it POP: the melody, the form, the lyric – the stuff that makes those songs accessible to the average listener.

That’s the magic of those Gershwin and Cole Porter tunes. They have recognizable hooks, memorable melodies, lyrics that are poignant and clever and clear. And before bop came along, the way those tunes were played allowed them to retain their accessibility. If modern jazz musicians are committed to the musical freedom they’ve grown accustomed to, the average listener is not going to follow them there. That’s true regardless of the tune.

The biggest mistake jazz has been making in the last 50 years (and there have been many, IMHO) is that it stopped trying to appeal to the average listener. Only 3% of Americans listen to jazz because most jazz musicians seem to think that 97% of Americans don’t deserve to be part of their club. I don’t think most of them do it consciously, but the way they play is too far out for most people. And generally it doesn’t seem to bother them that hardly anybody “gets it”.

In most genres of art, if you’re doing something that nobody “gets”, you have to change what you’re doing. I mean, it’s fine to play however you want – but if what you want is a larger audience, you have to consider where those people are coming from and play FOR THEM. That’s what distinguishes pop from everything else – and Louis Armstrong, Ella Fitzgerald, Fats Waller, even Dizzy Gillespie until about 1946 – they were making POP music. They were playing FOR their audience.

I found your article because I am making a jazz record and looking for coverage. But I didn’t plan to write you a diatribe – couldn’t help it. I’m not a jazz musician, I’m a singer/songwriter. I love American pop music. I love most of it, from every era, and I have a special love for pop from the 1930s and ’40s. I’m making this record because I adore the American songbook, and it saddens me that those songs are being thrown on history’s ash heap because jazz has become a private country club for wine sniffers and smarty-pantses. I don’t want in that club, I just want to spy for a minute and smuggle out some songs.

Anyway, I’d like to know what you think. Here’s my Kickstarter for the album.