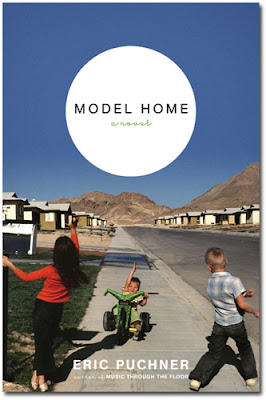

A fine new book with a perfect-pitch Southern California setting, has just dropped: Model Home, which starts out in an ’80s gated community, is the first novel by Eric Puchner, whose Music Through the Floor provoked Charles Baxter to call it “the most auspicious debut of a short story collection that I have encountered in years.” Model Home looks at a family that’s driven by golden dreams, but finds itself downwardly mobile: It’s the perfect novel for the West Coast’s brutal Great Recession.

Puchner has an understated, almost Chekhovian touch, as well as a quiet humor. Unlike a lot of Gen X writers, he’s not into comics, sci-fi or other hip genres — he’s an old-fashioned craftsman, sort of refreshingly square. He’s also got excellent taste in rock music, especially ’80s alt-rock, as you can see in this NYT piece. (I should add here that Puchner, who lived in the Bay Area for years, where he was a Stegner Fellow and taught at Stanford, has moved to LA, where he grew up, to teach at Claremont McKenna College and has since become an occasional drinking buddy.)

Here’s my Q+A with Puchner, who appears at LA’s Skylight Books this Thursday and embarks on a national tour in March.

Model Home has a very distinct – and distinctly Southern Cal – setting: A nouveau-riche gated community close enough to the ocean that surfboards seem to be everywhere. What made this the right place to start the novel?

Well, part of what the novel’s about is the phenomenon of the gated community, and how the rise of these enclaves has shaped our landscape and our sense of community and the great geographical and ideological schism that’s occurred between where we sleep and where we earn our livings. That sounds high alutin’, and the honest truth is that there’s something very attractive about some of these places: Warren Ziller, the father in Model Home, loves where he lives, and in part I wanted the first part of the book to counter the whole cliché that the suburbs are inherently evil and devoid of culture. (Just look at the great music that came out of the South Bay in the eighties, when the novel is set).

The second half of the book takes place in a very different kind of gated community: a block of tract homes in the middle of Antelope Valley, designed to lure lower-middle class Angelenos out to the desert where they can afford to buy their own homes. The Zillers end up living out there by themselves, in this sort of post-apocalyptic setting where it’s too hot to go outside and the coyotes are eating each other. So I consciously structured the novel to contain these two polar opposites, these two versions of the Californian dream.

Your stories and the novel seem to have a gently sardonic tone, a minor key of black humor, in common. Can humor or irony undercut the emotional impact of a scene, or do they work together?

Well, of course I think they work together. Who was it that said Waiting for Godot was the greatest tragedy of the 20th century? It’s a play that has its roots in vaudeville, and it makes you laugh and gasp for air at the same time. It’s also extremely moving. It’s almost a paradox, but I actually think that writing a scene with too much gravity is more likely to deplete the emotional impact: you need that lightness of tone, that friction, or else you’re doing the emotional work for the reader and letting him off the hook.

I have to say, too, that I can’t imagine trying to capture the absurdity of contemporary American life without humor. Laughter and despair, they come from the same place for me, and I’m interested in mining that place in my work.

How much is this book and its characters inspired by your own life?

I was a teenager in Southern California in the eighties, and we were downwardly mobile in something of the same way that the Zillers are — but everything that happens is utterly fictional. The characters are completely made up and bear absolutely no relation to my family (thank god). I do feel it’s in some ways a book about my father and about my own youth — but it’s an emotional resemblance, not a literal one.

You’re back in LA after living for years in the Bay Area, traditionally considered the seat of culture and literary life on the West Coast. By contrast, how does 21st century Southern California strike you?

I absolutely love San Francisco, but I have to say there’s something refreshing about the weirdness and messiness and unrepentant ugliness of L.A. In some ways, San Francisco has become a bit like Paris or Manhattan: a beautiful city in a bottle (or in quotation marks). It’s got this rich cultural history, but artists and writers and musicians can’t afford to live there anymore. In L.A., there will always be pockets of affordability, and so there won’t ever be that sort of cultural diaspora, I don’t think. Also, it was born wearing quotation marks.

And for a city that makes it’s money off the movies, there are terrific bookstores. Skylight Books is fantastic.

There have been a number of good Gen X novels and memoirs set in the ‘80s recently. What do the Reagan years mean to you? Culturally, musically, politically or otherwise.

That’s a pretty big question, and hopefully I already answered it by writing the novel. It would take another 360 pages. So maybe here’s where I tell people to read the book?

I’m nearly 100 pages into Model Home and I can say without hesitation that Puchner is the best new fiction writer I’ve come across in years. I can’t put it down, even though I already had two other excellent books going when I started reading it.