Fear of missing out on cultural turning points is a significant New York preoccupation. My own incessant curiosity takes me to small urban churches, inside security zones requiring a QR code (such as the Columbia University campus) and – as of the early hours of 2025 – to a 3 am video stream of the Berlin Philharmonic Ochestra’s New Years concert that originated as 2024 had one foot out the door.

These events aren’t necessarily the best I heard in 2024; I am spotlighting the intriguing and the unexpected. I don’t always claim to have gotten my arms around these events. But then, I quite like being in over my head

Starting with …

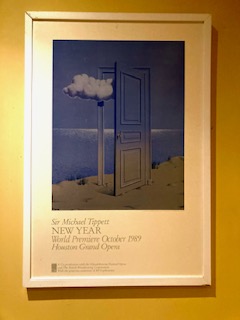

Michael Tippett’s opera New Year (see above poster) has been seldom heard since its 1989 Houston premiere — which I attended and loved and was told exists on a still-unreleased film. The piece has resurfaced in Glasgow, of all places, and I heard it in April in a BBC concert performance conducted by Martyn Brabbins. The recklessly flaky plot (devised by Tippett, who wrote his own libretto) is centered around an agoraphobic woman who is visited by aliens, most prominent among them the legendary Merlin the Magician. I know of no other opera score with such a density and variety of orchestral sound, often including electric guitars. There are long solo set pieces, incredibly abrasive ensembles and a Caribbean element for a character originally played by Bill T. Jones. Amazing, overwhelming, bewildering — New Year is a testament to the imaginative powers of the human mind. Look out for a coming Tippett revival with new recordings of his major symphonic and operatic works: Both philosophically and musically, these pieces challenge the subtle modern pressures to be typical — your smart phone anticipating (and dictating) your every step, your auto-correct finishing your sentences in typical ways, and emojis that package your intentions in small, even more typical icons.

The Berlin Philharmonic added more credibility to its world’s-greatest-orchestra reputation during its 2024 U.S. tour under Kirill Petrenko, who may not be a camera-commanding presence but is maybe the single greatest conductor out there. Their New Year’s Eve concert, as seen in a live stream, had star pianist Daniil Trifonov on a new artistic level in Brahms’s Piano Concerto No. 2. He has always been hugely impressive, but has he ever been more moving, with bold, personal ideas at every turn? The Berlin Phil definitely knew what it had; both orchestra and Petrenko were with him at every turn.

The Cincinnati May Festival had a guest curator in the form of the expansive, extravagant, socially-conscious composer Julia Wolfe. The programming featured her own choral works (such as Anthracite Fields) plus those of her colleagues from the Bang on a Can composer collective, David Lang and Michael Gordon. Thus, Cincinnati had the coolest classical music festival east of Ojai. Broadcast recordings of Wolfe’s Her Story (among others) suggested the normally magisterial May Festival Chorus was chanting, shouting, rocking and rolling (sometimes simultaneously) — bolstered by the all-female new-music vocal group the Lorelei Ensemble. I have no idea how Her Story or the other Bang on a Can pieces fared with the audience, but with the Cincy Symphony at forefront of progressive programming in recent years, one might well see a large Ohio contingent in North Adams, MA for the next summer’s Bang on a Can LOUD Weekend.

TENET Vocal Artists and Piffaro the Renaissance Band celebrated the easily-missed 650th anniversary of the death of poet Francesco Petrarch with an Oct. 18 concert titled “Triomphi” at Columbia University’s St. Paul’s Chapel. Organized around Petrarch’s principles of truth, eternity, fame etc., music was drawn from the fascinating cusp between Renaissance and Baroque eras where aesthetic rules were up in the air. Whether entrancing or just engaging, the seldom-heard pieces by Lassus and Cavalieri consistently made Petrarch’s words and worldviews shine — and they were presented in sympathetic context and sung with great comprehension. The strangeness of this music — melodic contours, unexpected cadences, irregular rhythms — was strange no more. Instrumentally, Piffaro set a new standard for themselves. I didn’t know it was possible for the players of shawms and other arcane instruments to keep getting better, but they are.

Res Facta Vocal Ensemble’s Sept. 6 Thomas Tallis concert, titled “Variis Linguis” and led by Ryan James Brandau, was aggressively recommended to me by a friend but fell on a day when my cat was having eight teeth extracted (with an uncertain recovery time). Yet, arriving late at Basilica of St. Patrick’s Old Cathedral on Mott Street in Manhattan, I was instantly enveloped in an atmosphere of rich choral sound inflected with such a rare understanding that your ear never needed to search for a through-line in this heavily-layered 16th-century music. The high point of this (and any other) Tallis program was Gaude gloriosa: The more one listens to this piece, the more one finds feats of word painting, voices branching off from each other, and mysteries around the music’s original purpose — giving you an encapsulated world unto itself in 17 minutes. New York City’s early music world doesn’t have London’s many period-instrument orchestras but, but we have great vocal ensembles — plus augmented by visiting groups brought in by the Miller Theatre at St. Mary the Virgin and Music Before 1800 (see below) at Corpus Christi Church. .

And then there’s the Philadelphia vocal invasion …

Variant Six, which has singers in common with Philadelphia’s The Crossing, seems to be up for anything, modern and ancient, and sang madrigals by Gesualdo and Monteverdi in the Brooklyn Art Song Society’s Histories III program on Dec. 1 at Roulette Intermedium performing arts center. The idea was to contrast 17th-century innovators with a second half featuring BASS’s own art song recitalists singing Wolf and Britten. Problem is, Variant Six has such tight chord tunings and artistic confidence that it outclasses everybody else within earshot. This group shouldn’t have guest slots but programs all to themselves.

Junction Trio — that part-time union of violinist Stefan Jackiw, cellist Jay Campbell, and pianist Conrad Tao — converged for a Nov. 1 concert at the 92nd Street Y. The program included Shostakovich and Zorn, but the Brahms Piano Trio Op. 8 showed why this group should have an executive pass in the chamber music world, or at least a good recording contract. Pianist Tao, for one, is a composer himself and thus brings the group closer to the music’s inside story than one can typically hope for. What’s especially remarkable is the ease of expression. Energy, technique and musical meaning are all one, and flowing effortlessly.

Ousleyfests — as they are called among New York classical insiders — are concerts produced by Andrew Ousley’s Death of Classical organization in unconventional venues like crypts, catacombs and caves — and, on Oct. 11, at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine’s underground space where bishops and deans are laid to rest. The program was titled “Into the Light,” featuring works by Caroline Shaw, Juhi Bansal, Andrew Yee, David Lang and Osvaldo Golijov played by the NOVUS ensemble from Trinity Church Wall Street. The most successful performance was Golijov’s Tenebrae, which was written partly in response to a Israel-related conflict from years past but felt like a much more relevant prayer today.

The Cleveland Orchestra’s Jan. 21 at Carnegie Hall concert under Franz Welser-Möst reclaimed Prokofiev’s forever-troubled Symphony No. 2 — and that was indeed a feat. Though the composer described the 1926 symphony as being made of iron and steel, I would call it a tsunami filled with wrecked, random artifacts of the lives and cultures that it has swept away. That may not be a flattering description, but the fact that any description at all is possible with such a chaotic piece is in fact a triumph. The Clevelanders again demonstrated their transparency and accuracy, as well as Welser-Möst’s x-ray vision. Surprisingly, the orchestra’s recording is strangely disappointing; maybe you need to be in the same room to feel the visceral sweep of the piece.

Grounded, the new opera by Jeanine Tesori and George Brant that I heard on Oct. 19 at the Metropolitan Opera, was one of the season’s more controversial events. Previously heard at the Washington National Opera, this work about a modern drone-warfare operator suffering from PTSD had a troublesome birth that gave its migration to the Met an aura of doom. Despite a dazzling, technologically-advanced production by Michael Mayer, some critics dismissed it, some viewers loved it and Met chief Peter Gelb complained that personal aesthetic biases among the opinion-makers clouded the piece’s reception. To me, Grounded represents a new operatic mutation, one that’s more artistically cooperative than usual: Here, the composer knew when to step aside and let the production, libretto and individual performers such as Emily D’Angelo (in the photo above) carry a kind of story that has never been told on the opera stage. It’s not the about the score but the total package. New opera needs to be something other than old opera with updated costumes; its stories need to be told on their own terms.

Bruno Mantovani needs little introduction in Europe but much explanation in the US. He has nothing to do with the light-classics maestro of the 1950s with a similar name: he is a fearless beyond-Saariaho composer with a prestigious track record. His latest stage work, Voyage d’automne, is the true story of French intellectuals who were lured into a 1941 Nazi propaganda event and thus, in their own ways, became collaborators. As premiered in Toulouse, the radio broadcast alluded to the piece’s less-realistic psychological realms where, one can argue, opera belongs. Watch for this piece. It will get to the U.S. sooner rather than later.