So much stimulating, challenging music threatened to overflow and overload the Tanglewood Music Festival’s annual composer’s week that one had to stand back and realize how radically this bucolic setting in Lenox, MA diverges from the typical summertime concert life of major orchestras. The closest thing to recreational listening over the 42 pieces played July 25-29 was the Boston Symphony Orchestra’s performance of the anguished Tchaikovsky Symphony No. 6. Elsewhere, even familiar composers were heard on highly unlikely artistic paths. Was Copland’s jazzy 1926 Piano Concerto really written by Copland? It sounded like a shotgun wedding of Gershwin’s An American in Paris and Bernstein’s Age of Anxiety symphony — although, in fact, it came before both of them.

The weekend represented a confluence of the Serge Koussevitzky anniversary celebration (150 years since the birth of this legendary conductor and Tanglewood founder) and the annual Festival of Contemporary Music, with the focus on two very-much-living composers, Tania León, 81, and Steve Mackey, 68. They curated not only their own pieces — often works that, for one reason or another, are easily lost in the shuffle but deserve to be more widely heard — but also those of younger composers, ones that León described as new or new-ish voices that speak in different accents. The Boston Symphony Orchestra concerts highlighted both León and Mackey’s orchestral works while also revisiting Koussevitzky’s remarkable ability to draw great music out of composers from Copland to Scriabin to Stravinsky — and to get a strong personality like Bartók to change the original, abrupt ending to his Concerto for Orchestra.

The contrast with the Bang on a Can LOUD Weekend up the road in North Adams, MA (Aug. 1-3, aka Banglewood) says much about the Tanglewood identity, which veers toward new music for traditional ensembles. As curated this year by California-born Mackey (whose primary instrument is electric guitar) and León (a Cuban-born modernist), the needle moved closer to the downtown-ish sensibility that’s heard from the boundary-free Bang on a Can composer collective. In fact, Bang co-founder (and much-awarded composer) David Lang was spotted at one of the picnic tables on the Tanglewood grounds.

“What brings you here?” I asked.

“Same thing that brought you here — new music!” he said.

Both of us were headed for a 6 pm Saturday concert, one that some visiting journalists from the Music Critics Association of North America missed amid the numerous other events that day. How much new music can you take before your ears fall off? (Also, dinner was best sought off campus due to the Tanglewood’s sticker-shock food prices – on the cutting edge of inflation).

Nonetheless …

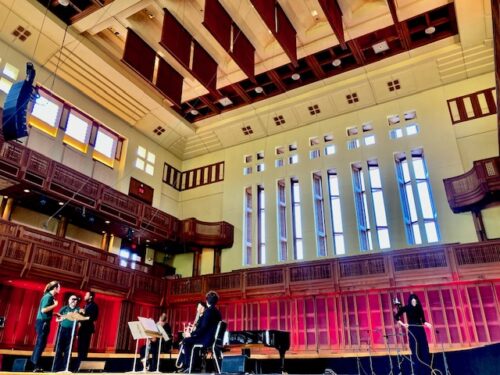

The New Fromm Quartet played Mackey’s 2012 One Red Rose and León’s 2011 Cuarteto No. 2 — both major but seldom-heard works that significantly changed the overall profile of both artists. Bumping into a fellow journalist afterwards, we simultaneously exclaimed, “This is the highlight of the festival!” (We could safely say this because we only had one concert left to go.)

The rigors of the string quartet medium bring out the best in these composers, no doubt challenging them to strongly articulate the deep feelings of loss that envelop both pieces. León’s piece meditates on her now-deceased mother’s final years in dementia. In contrast to her earlier, more strictly organized modernist works, this one begins by skittering off in all directions, with a brief shower of pizzicato, attempted fugues, moments suggesting affectionate repose and stark chords suggesting emphatic stubbornness, the first movement ending abruptly as if in mid-sentence. Solos — some plaintive, some organized with other instruments — coalesced into a faltering, shivering dance. The third movement is truly splintered, leaping out in a different direction every five seconds or so, separated by pauses and an occasional flicker of coherence. A long-breathed cello line forms a frame around all of this activity, though the final moments are such an abrupt, inconclusive ending that one hopes the ghost of Koussevitzky will induce her to rethink it.

The title of Mackey’s One Red Rose refers to the flower Jacqueline Kennedy was left with on the day of John F. Kennedy’s assassination — and to how the nation became united in grief. Such a musical stimulus might seem less personal than León’s quartet — Mackey was 7 when Kennedy died — though the composer seems to draw on more than the event. The music tells me that he also laments the loss of Kennedy’s world in the following decades. Unlike other Mackey pieces which observe and comment upon life events, this one is felt from the inside out in all of its dimensions. It may be his best piece so far. The quietly arresting opening moments are a disparate duet between violin and viola, the former with an introspective, repetitive three-note motif, the latter with a long-breathed lyrical viola part that seems to ask questions that it knows are unanswerable. The five short studies that make up the first movement are inventive in the extreme, often repeating ideas obsessively with great effect. Thereafter, the pieces ceased to be meditation on JFK and became simply a rich exploration of Mackey’s interior world. Often there were simultaneous musical ideas — busy, contrapuntal writing juxtaposed against lyrical lines of considerable emotional depth — that would capture one’s attention on their own but together have synergy, even as they grow increasingly distant from each other. Performances by the New Fromm Quartet were technically secure but so cognitively attuned to the music that the pieces took on an epic quality, particularly Mackey’s. (This program will be repeated at 7 pm on Aug. 2nd at the Experimental Media and Performing Arts Center, EMPAC, in Troy, NY.)

I could go down the list of the many other pieces I heard — by Lembit Beecher, Vijay Iyer, Niloufar Nourbakhsh, Dai Wei, Salina Fisher, Nick Diberardino, Angelica Negrón, Ileana Pérez Velázquez, James Lee III — but without doing them justice. Let’s just say they all fell on welcome ears in one way or another, and in cases where a repeated hearing wasn’t so welcome, the next piece by the composer was. Of course, so much music heard in a short period of time inevitably means that one doesn’t take in everything there is to understand. However, the tightly-packed festival approach is valid because of the critical-mass factor. Single pieces here and there may not make a great impact, though if heard as part of an overall zeitgeist in the making, one could zero in on how similar techniques were used by different composers. The polarity between tonality and atonality seemed quite outdated.

Most telling were the song cycles, Beecher’s Three Immigrant Songs and León’s Atwood Songs, in which lack of tonal allegiances allowed freedom of word settings. No false sense of symmetry was expected or utilized. Of course, there were flashes of traditional functional harmony as part of the overall poetic landscape. But the music allows the words to be what they are and to have a more open-ended meaning.

And what of the Boston Symphony Orchestra?

Assembling a series of chamber-sized new-music concerts is one thing, but it’s another to have major pianists doing concertos — pieces commissioned by Koussevitzky, of course — that aren’t likely to figure into their future repertoire. Paul Lewis was the soloists for the Copland concerto, Jean-Yves Thibaudet was on hand for the super-virtuosic Khachaturian Piano Concerto, Op. 38 and Yefim Bronfman was in for Scriabin’s Prometheus, the Poem of Fire (which also featured the Tanglewood Festival Chorus). These are not heat-and-serve pieces, but they would almost have to be recycled from the Symphony Hall season in Boston (Scriabin especially) in order to have them in good working order amid the hectic Tanglewood schedule. All were given optimum performances. Okay, one might argue that Lewis, classicist that he is, wasn’t ideal for Copland, but his rendition was deeply committed and skillfully negotiated the abrupt transitions that the concerto constantly throws at the performers.

Music director Andris Nelsons has come in for a certain amount of criticism for what have been termed auto-pilot performances. Well, all conductors have them, and Nelsons seemed highly engaged all weekend. The Stravinsky Symphony of Psalms was full of imaginatively conceived, sharp, dramatic contours — all text driven, all making sense — and the Tchaikovsky Symphony No. 6 was one of those performances where conductor and orchestra were deeply immersed, moment by moment. Nelsons does tend to have a sheen, not unlike Claudio Abbado”s, that can give the impression of detached slickness in some repertoire or add an attractive aura of clarity in other, more complex scores. To judge from recordings of Koussevitzky, his Boston Symphony sheen seemed to come from a near-superhuman concentration on the harmonic needs of the moment amid the grand architectural scheme of a piece. But, even though his concert clothes still hang in the closet of his Tanglewood home, Koussevitzky departed long ago — and Nelsons’ Tchaikovsky was, to my ears, bristling with the kind of life that made me momentarily forget the great Tchaikovsky performances from my past.