On many days lately, the last places I’ve wanted to be are 2020 and 2021. And living outside of the present is clearly optional.

Encouraged by pandemic restrictions, I retreated to my decade of origin — the 1950s — creating in my apartment a musical time capsule that could only have been experienced in 1960 or before. That’s thanks to Brooklynites who have been clearing out their closets while stuck at home, finding all manner of often-unplayed LP records and depositing them in second-hand stores, where I’ve stumbled upon them at giveaway prices. Those neighbors have allowed their past to be my present.

The “unplayed” part is a key point: Even in near-mint copies of LPs, you feel the intervening decades in surface noise and visible wear on the cover. But these records — whose unplayed state is apparent in how the discs hug the turntable’s spindle — aren’t just objects from the 1950s. They are the 1950s.

The listening experience isn’t necessarily better. An unplayed disc of Arturo Toscanini conducting Beethoven with the NBC Symphony actually sounds strident in manner and puny in sound compared to later issues. But it’s real. It’s what people heard then.

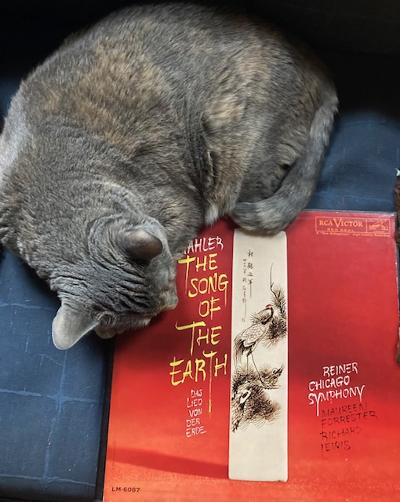

Many of the covers for classical albums were changed after the first few runs of pressings. The brilliant, Chinese-red two-disc box for the Fritz Reiner recording of Das Lied von der Erde was replaced by something less lush, and the piece itself was squeezed onto a single disc (rather than three sides plus Haydn’s Symphony No. 88 on the fourth side). Did anybody hear a difference in these later issues? Maybe not. Expansive, searching tempos were not what was happening then; that was put to rest after World War II. Everything became faster and cleaner, with the general ideas of the music more easily apprehended. These post-war performances weren’t particularly cramped by being slotted into smaller spaces. The music’s deeper meaning was still there, but it went semi-underground.

French recordings from the 1950s aren’t the sturdiest performances to be found, but they reflect a specific time and place in history with their sound and manner. I’ll take any Reynaldo Hahn recording from that era — though, oddly enough, not Offenbach, who seems too lighthearted for these times.

My 1950s jag started with a Carroll Gardens antique store called Yesterday’s News in the late fall, when it took in what was reportedly left-over inventory from a Brooklyn record store that went out of business probably in the early 1960s. When a second lockdown seemed to be on the verge of happening in New York, I was out getting a haircut while I still could. Suddenly, on a patch of sidewalk in front of Yesterday’s News, there appeared several cartons of albums seeing the light of day for the first time in decades, seemingly untouched by time.

Similar sleeping beauties appeared in another collection, said to be from Forest Hills, Queens but including recordings from the Bridgeport, Connecticut Public Library. (One of the prizes from that lot, Chausson’s Symphony in B-flat conducted by Ernest Ansermet, had been checked out exactly once.) Other pristine collections found their way to Manhattan second-hand stores such Mercer Street Books and, of course, Academy Records on 18th Street. Long forgotten names such as pianist Alexander Brailowsky — in a first-class production of Chopin and Saint-Saëns concertos with the Boston Symphony under Charles Munch — impatiently leapt out of my speakers as if to say, “What took you so long to find me?”

One rainy day, when biking home from an afternoon of volunteer work in Red Hook delivering food to shut-ins, with a complimentary box of vegetables I’d been given for my time, I noticed that the unassumingly-named Record Shop on Van Brunt Street had lights on, even though the doors were locked. I tapped on the window; the owner let me in; I traded vegetables for vinyl. Among my finds: an electronic music interpretation of the Tibetan Book of the Dead by Pierre Henry. This was a little past my 1960 cutoff point, but how could I resist something that The Guardian put on its list of ten weirdest recordings found on Spotify?

The pop music discs that turned up from these diverse sources formed an essential part of the time capsule. It was all pre-rock. Doris Day’s 1956 Day by Day album had muted, Paul Weston arrangements for small ensemble, with Doris in a period when she still had echoes of her big-band authenticity and wasn’t yet the commodity that she would become. The super-suave Ivy-League dance music of Les Elgart, whose music seemed made to play on those massive hi-fi consoles, no doubt easing PTSD from World War II and so much else. And it works for me in 2021. This wasn’t nostalgia, exactly; it was forming a past that, in many ways, never was.

The 1950s were no less threatening than our own times, but at least we know how they came out: Senator Joseph McCarthy was ultimately disgraced and the world-ending nuclear war that everybody feared didn’t happen. But special-interest groups were locked into place in ways that would explode, rightly, in the following decade. My home life at that time was sort of an Eisenhower-era Long Day’s Journey into Night, full of secret addictions in split-level subdivisions that had recently been corn fields. Everybody talked but nobody said anything.

Anyone who was ‘singing along with Mitch’ (as in Mitch Miller, of TV and Columbia Records fame) was doing so on the edge of a volcano — or maybe a sink hole. It’s hard now to imagine a period when we’d spend our time doing anything so useless as watching him conduct us in “The Yellow Rose of Texas.” But we did. And now, Mitch — who was generously represented in the Yesterday’s News collection — was the one thing that didn’t make my time capsule. Anomalies and aberrations (which I love) are one thing; irrelevance borne out of trivial inauthenticity is another. Some friends have compared the 1950s to The Matrix: So many of us were asleep, trapped in a dream (or nightmare) but didn’t know it.

But those who were awake were making music in ways that had a magnetic tension, working inside strict frameworks (what a genre could and should be) but finding great invention within them. Miles Davis, for one: later in the 1960s he would let go of all allegiances to tonality, but in the 1950s he pivoted around tunes like “On Green Dolphin Street.”

If the 1950s world seems simpler than ours, it’s because there was more veneer. And over the past 15 months, veneer amounted to much more than shiny superficiality: it provided padding from the reality outside my door. (That reality still includes helicopters buzzing overhead when protests erupt in the parks around my Brooklyn neighborhood.) The main advantage of the 1950s is that the world was smaller. Choices were fewer, in terms of what music was available and what the music was up to. Therefore, in a time where every day brings new evidence that the United States is in the midst of an undeclared civil war, a more contained world inside my four walls creates an illusion of safety. Of course, I know that I have a mere keyhole view of reality. But I don’t have to confront that fact every waking moment of the day.

Nobody can speculate with any accuracy where the world is going right now. Maybe that’s why even some of my more intelligent friends have become terrifyingly devoted to illogical conspiracy theories. But in these musical artifacts of the 1950s, I know where this music is headed, and that predictability doesn’t make the experience any less substantial. Doris Day has not been a stranger to my 21st-century life, thanks mostly to my optometrist, who often has her playing in his examination room. But I never fully realized how much digital remastering bleaches out her voice until her Day by Day album turned up at Yesterday’s News. Heard in mono, the voice arrives from my turntable in three dimensions, deployed with unerring subtlety. There’s a world of experience behind that voice, though for the moment in any given song, she’s telling you, “Just sit back and let me handle everything.” She isn’t always genuine — sometimes you catch her playing a role — but she is more often than not.

So often in this slow return to pre-pandemic living, I feel like my life skipped a year. Everything is as I remembered it, only what seems like yesterday was actually March 2020. Yesterday’s News is reverting to something resembling its previous inventory by taking a break from the used record business: Hauling around these discs was taking a toll on everybody’s back. But even if it seems like time has been lost, I gained a listening year that was unlike any other.

Plus storage problems.