Violinist Camilla Wicks was not being modest, but realistic.

The clear, clipped voice at the other end of the phone was neither astonished nor impressed to learn that her 1952 recording of the Sibelius Violin Concerto was a collector’s item that, in its original LP incarnation, sold for as much as $125.

“It’s not that good,” she said, sounding mildly exasperated.

Oh, but it is. And I wonder what would she say if she saw that a re-issued CD of the Sibelius on EMI is now selling on Amazon.com for $985?

Wicks, who died Nov. 25 at the age of 92 in Florida, was the supreme master of her instrument. There are many of those, then and now, though rarely in my travels among the historic recordings of great violinists are masterful technique and depth of insights so inextricably linked, so much one and the same. Sibelius said her 1952 recording of his concerto was his favorite; now, you truly hear what he means. Her conviction is such that in phrase after phrase, you think “That’s exactly what this music means” — but in a phrase reading that’s only possible with a technician of the highest level.

Nothing is suggested or implied in her playing; it’s all there in front of your very ears. At times her playing feels spontaneous to the point of recklessness. Yet all of the chances she takes — whether great or subtle – always worked out with an exalted level of excitement. To say that she projected bristling energy seems trite; her energy was that of deep musical discovery.

How could she possibly be so nonchalant about such an achievement in her Sibelius recording? Usually when artists say that, there was something in the recording process that put them off. And in my phone interview with Wicks, somewhere around 2008, she explained that the electrical currents in post-war Scandinavia were unreliable, causing a problem with the recording machines that apparently weren’t caught until it was all over: The slow movement becomes subtly slower and not because she and conductor Sixten Ehrling played it that way. I can’t say that entirely makes sense to be, but if you you say so, Camilla …

Some Camilla cultists swear by her 1953 live Beethoven Violin Concerto recording with Bruno Walter and the New York Philharmonic. I like it very much, though her innately restless temperament feels not entirely suited to this fundamentally contemplative concerto. To me, Wicks is heard at her height in her 1985 outing with the Walton Violin Concerto. It has all of the technical mastery of past decades. Wicks’s particular brand of lyricism — steely but rhapsodic — is heard at its best here. Her comprehension of the music’s thematic development is a revelation at every turn. It’s hard to say this is the best recording of the Walton concerto when the competition includes Jascha Heifetz. Let’s just say that the Wicks recording is my personal favorite.

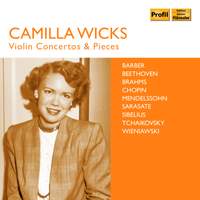

Two box sets, with much overlapping repertoire, impressively sum up her career. Camilla Wicks: Five Decades of Treasured Performances (Music & Arts, six discs) has a good mixture of concertos and chamber music. Camilla Wicks: Violin Concertos & Pieces (Profil, four discs), is concerto-heavy, including the Sibelius recording not found on the Music & Arts set. The Walton concerto is on a single Simax-label disc with the Oslo Philharmonic Orchestra under Yuri Simonov.

Time and again, listeners ask why wasn’t she better known. She was — in distant decades. Born in Long Beach, CA, she entered the Juilliard School at age 13, was performing in Carnegie Hall at age 18 and had a major career in the 1940s and ’50s. The Washington Post obit tells us she was married in 1951, had five children and then hung up her violin in 1958 to be a mom. But that move was perhaps not entirely voluntary.

Part of the problem was less-enlightened views toward working mothers. Wicks told me that agents and managers grew tired of having to work around her pregnancies. And maybe the concert dates she was landing weren’t as attractive as they could be. I found her name in the Philadelphia Orchestra archives in a concert conducted by Eugene Ormandy that had Strauss’s Also sprach Zarathustra in the first half, but a lighter second half that featured Wicks in Ravel’s relatively brief, flashy Tzigane. She deserved so much better.

The marriage ended as her teaching career picked up, with appointments all over the country, plus a multi-year stint in Oslo, since she was of Norwegian heritage. Any number of radio recordings have come out of that period — including the Walton concerto. Ultimately, she retired from the San Francisco Conservatory in 2005, according to the Washington Post.

Somewhere during those teaching years, she decided she would learn the Berg Violin Concerto as a farewell of sorts to performing. I don’t know how extensively she performed it. But it was at this point in our interview that she seemed to truly appreciate her own worth. Learning, rehearsing and performing the intellectually and technically demanding concerto, she discovered, as far as her playing was concerned, “it was all still there.”

Does anybody have a recording of that one?