How often can you say that the Metropolitan Opera rocks?

That happens in much of the new recording of Porgy and Bess taken from live performances of the Met’s hit production. But the price of capturing that live energy was surprisingly high.

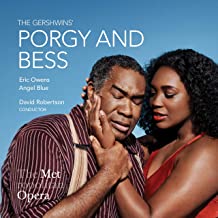

The Warner-label issue is an excellent souvenir of the production starring Eric Owens and Angel Blue under the baton of David Robertson. I’d love to say the recording is an overall triumph at a time when the Met badly needs exuberant press. But for all of its strengths, it’s a lustrous but secondary companion to the previous outings by Houston Grand Opera (RCA) and the Glyndebourne Festival (Warner Classics).

Listing the recording’s attributes, you wonder how greatness could elude it. But opening night problems that I thought would iron themselves out as the run went on did not. Owens and Blue never made a good vocal match, he with his wiry Wagnerian bass-baritone and she with a lush, expansive tone and stentorian manner that made her born to sing Tosca. The cast looks like an operatic who’s who: beyond Blue and Owens, there are Golda Schultz, Latonia Moore, Karen Slack, Denyce Graves and Ryan Speedo Green. And all of them have their moments, though not always in the right places. In the opening bars of “Summertime,” Schultz, for one, misses the languid ease of the music, forcing her voice from what may have been an acoustically unfavorable region of the set.

Gershwin’s score is music that captures the evening humidity of the South Carolina air. But much of this recording feels air-conditioned — a high-quality problem, I know, and one often overshadowed by great ensemble passages when chorus, orchestra and soloists fuse into a dramatically compelling entity.

The production was the Met’s biggest hit in years — but maybe the public was just incredibly glad to revisit the full opera. At least twice in the history of Porgy and Bess, the 1935 opera has been cut down to something resembling a Broadway musical, the first time being the 1942 revival after Gershwin’s death. The great rediscovery of the operatic version came from Houston Grand Opera in 1975: many of the cuts made in the original pre-Broadway run in Boston were opened — to the point where the piece was so long that only the most sympathetic productions made it work.

After that, there was a return to the (cut) 1935 Broadway version. Then came the 2011 Diane Paulus production that started in Cambridge and moved to New York: its cuts were draconian even by Broadway revisical standards. The project raised the profile of Porgy and Bess as a property —- not least thanks to Audra McDonald as Bess — but without representing the real sweep of the piece.

What played at the Met was the full opera, in an intelligent new edition that came out of the University of Michigan in the past few years. The orchestration feels much more transparent than before, though that could also be the work of conductor David Robertson. In its fullest form, the opera’s prelude has a full five minutes of musical scene-setting leading up to “Summertime.” In the new version, you get there literally in a minute — a quick prelude that gets right down to business. “The Buzzard Song” was, thankfully, cut at the Met: though it functions to prefigure the problems to come, it’s the score’s weakest song by far and ruins what is already some pretty fragile pacing.

At the end, when Porgy decides to go to New York City to look for the departed Bess, his climactic line, “Bring me my goat” (referring to the animal that pulled his wheelchair-cart around Charleston) has been sensibly changed to “Bring me my cart.” Still missing is “Lonely Boy,” a song that never really made it onto the stage; as a lullaby to an orphan, it has dramatically apt wistful lyricism, but it might feel redundant or second-best in a score that already features “Summertime.” (The only “Lonely Boy” recording I know of is on an RCA-label Marilyn Horne Lullaby album that’s been released under a few different titles.)

Another textual question is interpolations. They’re an accepted part of the Porgy and Bess landscape, but went a step further than usual at the Met, with Frederick Ballentine (Sportin’ Life) departing from the usual vocal line of “It Ain’t Necessarily So,” the chorus following right along with him. Such passages — as well as the later street vendor songs, some of the best music in the opera — represent a significant missed opportunity. On disc, the Met singers seem to be stepping outside their characters to show what their voices can do — and as much as those theatrical flourishes are impressive and add to the in-performance heat, they could just as easily have been integrated into their characters in ways that more completely revealed the culture of Catfish Row.

Whatever the edition, Porgy and Bess comes with an internal contradiction that begs to be resolved: It’s a deeply intimate story told in a grand opera context. (Just because the Paulus version was smaller didn’t make it more intimate.) And that goal seems even further away at the Met, in both the performances and, especially, in the recording.

For instance, in “I’ve Got Plenty of Nuttin’,” any hope of carefree breeziness is scuttled by Owens’s well-meant effort to make himself heard in the top balcony. (His is a voice built for majesty, not banjo songs.) In the sublime duet “Bess, You Is My Woman Now,” Blue punches the important notes at the expense of creating lyrical lines. This doesn’t mean they’re inartistic singers; they’re dealing with the reality of grand opera. The Alvin Theater, where the 1935 Porgy and Bess played, has a seating capacity around 1,400, compared to the Met’s 3,800.

For all its heat, the Met production lacked alchemy. The one place I’ve experienced that was a student production (yes!) at Indiana University in the 1970s. Maybe what Porgy and Bess needs is the kind of innocence that comes with a youthful, unfiltered cast that’s discovering the piece for the first time.

One piece of unexpected good news is that Porgy and Bess no longer stands alone as an operatic anomaly. For decades, there’s been nothing like it — in Gershwin’s output or anybody else’s. But I recently encountered the opera Harriet Tubman: When I Crossed That Line to Freedom. This is old news to those who closely follow the American Opera Project, which premiered the piece, with music and libretto by Nkeiru Okoye, in 2014. I finally caught up with it amid the current pandemic, when AOP began posting archival videos of its works on line. And Harriet Tubman is a deeply accomplished opera that uses the gritty-but-grand symphonic manner of Porgy and Bess as a jumping off point for something a bit more modern and able to accommodate more intensity and a bigger range of emotions. I long to hear it in better sound. But the point is that anyone who knows Porgy and Bess has a clearer way into this remarkable piece. And anyone who knows this Harriet Tubman opera will better understand the needs and the possibilities of Porgy and Bess.

While I haven’t heard this recording, I did attend one of the October performances of this Met run of “Porgy”. I’m happy to have traveled for it and to have experienced it in the house, but I had similar kinds of reservations with the experience, in the manner of your comments above. Vocally, the cast didn’t really blow me away, although they certainly worked well together as a team. It was a total surprise, in a bad way, that the opening chorus with the ‘Jasbo Brown Blues’ got cut. I hope that this was a decision purely in time interests, and not because the new edition cuts it. I would hope that the new edition provides all the material for a full-length version, and then individual directors can then cut numbers as they see fit. This assumes, of course, that someday we’ll get back to live theatrical productions in the foreseeable future.

In any event, the Met’s production was the first time that I’d seen anything like a proper full-scale production of the work, so for that, I’m grateful. As well, good to see things back in action on your blog here, as well as reading you at WQXR.

(Unfortunately, at the latter, you have to deal with the deplorable racist with the initials CF in at least one of your posts. That is not an extreme statement about him, but a simple fact. Evidence: CF uses the wrong, racist name in all caps for SARS-CoV-2 in a comment in the WQXR blog post “How the Sound of New York City has Changed During the COVID-19 Lockdown” by Karissa Krenz of 4/23/2020, where his racist comment is time-stamped Apr 26, 2020, 8:09 PM. Your own much friendlier comment from 2 days earlier is in that post as well.)