Getting to know opera via recording, as has often been said, is like on-line dating. No reason why it shouldn’t work. And it often does. Then you walk into something like Korngold’s Das Wunder der Heliane with well-founded hopes, and you leave trying to reconcile what you thought it was on recording with what you’ve just experienced. And if Leon Botstein and Bard SummerScape can’t rehabilitate the piece — as they have so many works — who can?

Photo by Stephanie Berger.

Premiered in 1927 and considered by its composer to be his crowning achievement, this extravagant, beyond-Richard-Strauss opera was met with a cool reception and ultimately forgotten, even after Germany’s wartime ban on Jewish composers was lifted. The 1992 Decca recording of the opera led by John Mauceri was a revelation to many, showing Korngold pushing his musical language to the bursting point. No wonder Heliane is sometimes called Korngold’s Elektra.

Yet why is the U.S. premiere only now being presented? The recording suggested that the piece was just too daunting and too expensive — with a potentially limited audience market — to hold up in any American opera house or festival. But Bard SummerScape has a history of doing just such works. So, in all fairness to the Christian Räth production (presented at the Fisher Center in Annandale-on-Hudson, NY July 26-Aug. 4), I went there not necessarily looking for a wholly successful rehabilitation. Partial success — or even an earnest, thoughtful attempt — can be just as fascinating. And that was surely the case here.

The Hans Müller-Einigen libretto might be described as a French Symbolist retelling of Fidelio, as incongruous as that might sound. Yes, there’s a prisoner of a totalitarian state, and the local dictator’s wife (Heliane) is faced with rescuing a would-be lover, known as The Stranger, who has achieved a Christ-like status among the masses. Meanwhile, she is put on trial for adultery. A blind judge shuffles in and out, probably from a Maurice Maeterlinck play. In what sounds like some sort of medieval parable, she is challenged to prove her purity by resurrecting the slain Stranger.

What do you do with that? Well, Korngold treated it to one of the most sumptuous opera orchestrations ever written. Sample, if you can, the Act III prelude, which has the composer trying to outdo Strauss, not in Elektra but in his more thickly upholstered Die Frau ohne Schatten period. Korngold just keeps coming up with one dazzling sound after another.

However, as Räth and designer Esther Bialas know better than any of us, opera needs sounds at the service of characterization. After an extremely promising beginning, about halfway through the first act Korngold seems at a loss for what to do. When in doubt, he just throws more instruments at a character or plot point — impressive but bewildering. No wonder the later Korngold took so readily to Hollywood film scoring: With the dramaturgical work done for him, he only needed to magnify (rather than interpret) what was already there. (He never knew how much he needed Errol Flynn.)

The rest of Das Wunder der Heliane is much more dramatically focused, but, like Die Frau ohne Schatten, it suffers from presenting something that we might now call Magic Realism without the back story and cultural depth that could make the characters more than a series of symbols and the plot more than a broad parable about the power of love and the hopelessness of totalitarianism.

The production often addresses that problem with imagery that echoes pre-World War II German Expressionism with its fantastical costumes and symmetrical stage pictures (achieved partly through computerized imagery) that feel extremely similar to photos from any number of theater and opera pieces from that period. To more seasoned eyes, the imagery sometimes intersects — not unhappily — with that of the 1930s Flash Gordon serial films, with extravagant collars and a gothic sense of malevolence. Sometimes I think Ming the Merciless (Flash Gordon‘s archvillain) has the most influential silhouette in modern opera stagings.

The vocal writing challenged everybody, as if Korngold didn’t want anything getting too pretty. I wouldn’t be surprised if Aušrinė Stundytė and Daniel Brenna, respectively Heliane and The Stranger, never went near this opera again. As The Ruler, Alfred Walker came away with his vocal composure intact, and you really wanted to hear him again. From the orchestra pit, Botstein took an integrated approach: While Mauceri’s recording seemed to ask how far the opera would go in so many directions, Botstein asked what it all adds up to. And I’m not sure if I can answer that question.

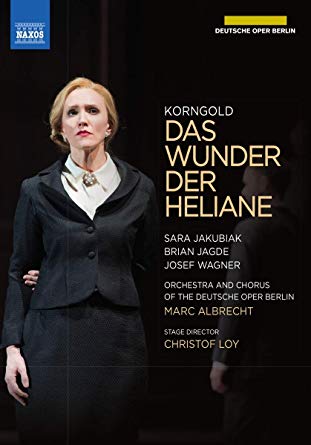

But the Naxos DVD that came out this summer is another story.

In this gray, spartan Christof Loy production from the Deutsche Oper Berlin, the first-scene exchanges between The Stranger and The Porter (who might be described as a relatively benevolent jailer) immediately resemble an encounter between twins . Brian Jagde and Derek Walton have the same hair and beards and are only in slightly different gray suits. From there on, most of the male characters (the blind judge an obvious exception) look like variations on each other.

My conclusion: This opera, at least in the first two acts, take place inside of a single psyche. It’s vaguely Jungian, with different personality aspects portrayed by different singers. This makes a certain amount of sense, since none of the characters but Heliane have proper names. Time and again, I thought about the old adage, “Your head is a dangerous neighborhood; don’t go there alone.” And in this production, the neighborhood had more to offer than a staging that tries to tell us that the story is in a real place. Das Wunder der Heliane is best kept in the world of the imagination, where outside rules don’t apply.

In Act III, of course, outside rules do apply, since the opera is invaded by a chorus that, until then, had been often treated like an offstage section of the orchestra. And that act does work in a more conventional operatic world, even in the climactic resurrection. But in any case, any route to the truth of Das Wunder der Heliane should scrupulously avoid anything real.

I’ve seen several productions of Candide. The best was a partially staged concert version by the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra about a year ago.

This was intended for your article on Leonard Bernstein.

Marin Alsop is the best Lenny conductor out there right now….though Nezet-Seguin is proving himself more and more….

Great review of ‘Das Wunder der Heliane’. I’d seen the schedule for this summer’s Bard SummerScape, and this looked intriguing for travel, but obviously I didn’t go for it in the end. I remember the existence of the Mauceri recording from the “Entartete Musik” series (great series, that, from Decca), but I don’t actually recall listening to the album at the time.

I did hear some Korngold at Santa Fe this summer, his op. 15 Piano Quintet, which honestly sounded more than a bit overheated and sprawling at times. I’ve actually gotten that impression a fair bit from various recordings of EWK’s music. Of course, neither of us would survive expressing the slightest scintilla of a doubt or reservation of EWK’s music to Jessica Duchen, the UK’s leading EWK fanatic (when she’s not understandably raving on her blog about her country’s pending mass suicide in the form of a hard Brexit):

https://theartsdesk.com/classical-music/theartsdesk-bard-summerscape-festival-2019-unknown-treasures-and-crosscurrents

In fact, come to think of it, I did see “Die Tote Stadt” a few years back in Dallas, fine production and performance, if again, the music is likewise a touch overcooked.

BTW, along with Carlo, I had a “Candide” observation for you also, in the wake of a recent local production here of “Candide”, but it was too late to post on your blog entry then (great reminiscence there also). This production restored “Nothing More Than This” towards the end. After reading your comments on your “Candide” blog entry, I see why its inclusion makes sense, since it does make the transition to the finale more logical / less illogical. However, one irony of the song is that it shows Candide finally realizing what Cunegonde had said way back in Act I, that she loved money and jewels, but he just blew it off. Part of me reacted mentally “well, dude, you finally caught on to what she said in your first duet way back then”. In other words, OK, maybe she is a bit materialistic and shallow, but she admitted it then, and the guy didn’t pay attention.

One other point that hit me in this local staging, much more than the more big-budget Santa Fe Opera staging that I saw last summer, was what seemed most wrong with the work. I’m not going to articulate this well, but it finally hit me that the problem with the work is that it violates one of the cardinal rules of drama: “show, don’t tell”. The voluminous presence of the narrator tells too much of the story, instead of just letting the events happen on stage. “The Lehman Trilogy” could get away with this (just saw the delayed HD-transmission today), because the complex nature of the story allows for a blend of the 3 actors both delivering dialogue and narration. Contrast this with the long-windedness of this “Candide”, where in the time it takes to last through the first part of the show, you can read the original Voltaire.

Overheated? Sprawling? Sounds like Korngold. As with so many composers, he has become more popular as musicians and audiences come to love aspects of him that previous generations disliked. The Violin Concerto used to be dismissed as sounding too Hollywood. Now, that’s why people love it.

EWK’s Violin Concerto is the one staple work of his at least with the SLSO, to be sure, although John Storgards conducted the “Tänzchen im alten Stil” with the SLSO a few years back. There’s nothing wrong with overheated or even sprawling Romanticism, as long as all the parts add up to a compelling listening experience. My problem with hearing a fair bit of EWK, mainly on record, is that the whole of a given work is often less than the sum of its parts, like that op. 15 suite. The parts just don’t fit. But if Stephane Deneve decides to program something like EWK’s Symphony, or the left-hand Piano Concerto, I’ll be first in line to give them a go.