The New York City subway is not, on any given day, the place to hear the music you need. It’s public in the extreme — in one of the world’s most public cities. And yet that’s where music ambushed me, a few months ago, in the form of a singer-guitarist whose high, sweet voice seemed to address my psyche with disarming directness.

He was hoping for $1. I gave him $5. He gave me a CD, maybe so that I wouldn’t forget him. And I won’t — in contrast to so much other commercial music that doesn’t even go in one ear and out the other.

Those more clued-in than I talk about how commercial music just isn’t there for them any more, and Joseph Keckler, in an essay titled “On the Redemption of American Culture,” makes a eloquent-though-grumpy case for why New York is on the cultural skids. And I’m sure he’s right, based on what the entertainment industry is handing the younger public. Then there’s a part of me that stands back and says , “What do you expect? He’s watching television!”

I haven’t trusted the entertainment industry for decades. I need entertainment like I need a Tootsie Roll. Also, musicians who have viability written all over them have told me about draconian “360 deals” when the record label claims pretty much everything remotely resembling profit for the sake of its promotion machine. They also tell me they can make more money busking on the right streets than playing in clubs.

My idea of a great Sunday is an ear-bending Elliott Carter string quartet marathon. In more serious new-music circles, New York has never been richer, and one need only go to the annual marathon concerts staged by Bang on a Can to know that. As for pop music, I get mine from what I call the rock stars next door. The culture that Keckler talks about is sort of a critical mass of like-minded work, one of the most obvious examples being the British invasion of the 1960s that changed American pop music.

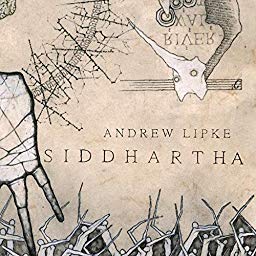

Here, I’m not talking about that kind of big picture; I mean individuals, who are often making music for themselves out of inner need. Philadelphia rocker Andrew Lipke makes his living in a Led Zeppelin tribute band, but has a sophisticated home studio where makes his solo albums that have the lushness George Harrison in his White Album period.

Some of these individuals are personal friends of mine — which is really neither here nor there, since the bottom line is whether these recordings demand repeated hearings. And they do. Are they original? Not in the sense that they’re re-inventing a genre or that they’re experimentalists redefining music in general. But their music is personal, and that counts for a great deal. They speak through pre-established genres, and say things with them that wouldn’t be said in strictly commercial circumstances. The chosen genre provides the floor plan and some sense for the exterior sound. Everything in between is theirs.

My subway buddy, for example. He’s enigmatically known as dwho; the name is probably riffing on The Who, but he sounds nothing like them.

His “So Cruel” is a song about extreme romantic desperation — fatalities may even be in the wind — that feels all the more effective for being handled with the sort of light touch associated with late-1970s Fleetwood Mac. The tempo is inviting, relaxed and vocal lines are sung with a gentle ache that seems breezy at first, but dark turns make way for a gently tortured guitar solo. “Without You” continues in that emotional vein, though with a more nervous rhythm track and more sophisticated vocal harmonies. It’s subtitled “the Dueling Guitars version,” and it’s not kidding: Two hot but different electric guitar solos unfurl simultaneously.

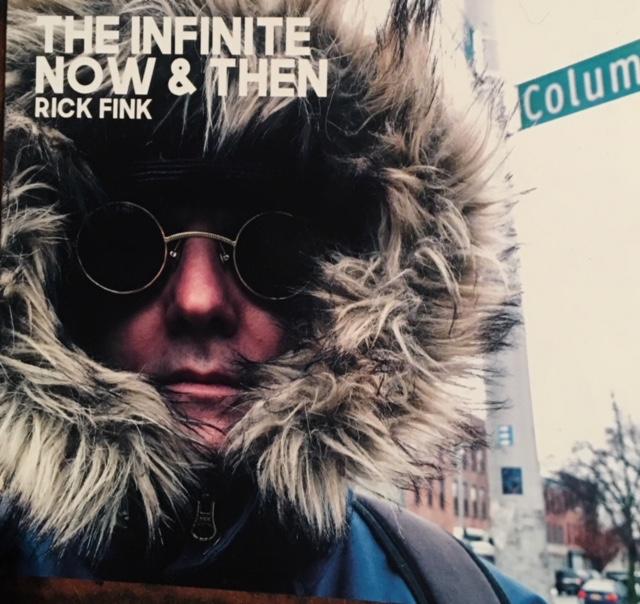

“The hand of fate has smacked my face and there’s no trace of you” is the emblematic lyric that begins “The Infinite Now & Then,” a solo album by Rick Fink, formerly of Gas House Gorillas. The album is a not-a-wasted-note knockout that mainly traffics in mainstream rock — even the old Lesley Gore hit “It’s My Party” fits in fairly well, though it’s transformed by Fink’s voice, which has a boyish ring but the heft and life-experience of an adult. And an angry one: Fink grabs mainstream pop gestures by the throat and shakes them until they say what he wants them to. And it’s not just with lyrics about the world going to the dogs: a malevolently creepy downward chromatic bass lines and other dark-shaded peripheral touches keep his music from being typical.

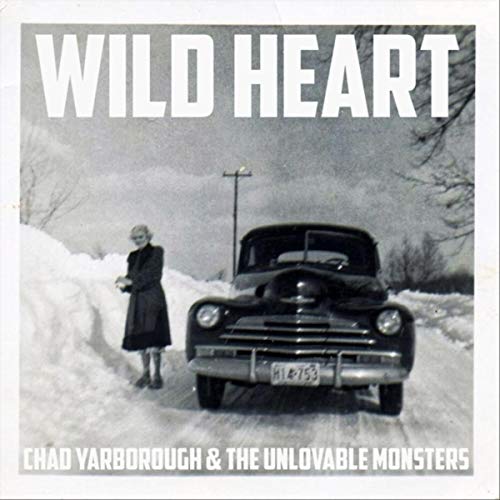

Chad Yarborough and the Unlovable Monsters put out a dandy rockabilly disc titled “Wild Heart” that initially seems like a high-energy romp aimed at those for whom there’s not enough Jerry Lee Lewis in the world. As narrow as rockabilly can be, there’s no lack of fresh ideas here. The chords are a lot richer than usual. And then, midway through the album, the songs start to become buoyantly nonsensical. Consider “Hard Rock & Harry Truman”: What is America’s 33rd president doing there?

But by then, the album has been making its own kind of sense. Some of the chord progressions are nonsensical — not incoherent, but more like somebody driving a high-speed car on country back roads and making a lot of impulsive turns this way and that. As with most road rallies, there’s that wild moment where you hit a dead end and start driving into a corn field. Yarborough does that. An improvisational sensibility is expected within a song, but there seems to be a degree of improvisation written into the creation of this one.

Andrew Lipke’s “Siddartha” reflects his recent forays into the classical world with arrangements that have string quartet elements and sophisticated harmonies that speak to his work with the cutting-edge vocal group Variant 6. Vocal arrangements feel as intricate as madrigals. It’s such dreamy stuff, with Phil Specter-ish walls of sound built out of harp arpeggios, violins played backward and stratospheric vocals, that the music could lapse into its own obscure lotus land. Yet a strong pulse is always maintained. The music’s relationship to the Hermann Hesse novella Siddartha seems distant at best, but after a certain point, you’re perfectly happy to be in Lipke’s never-never land.

What these artists all share are extraordinary voices, all hugely different but compelling on their own terms. And their packaging is meticulous. Lipke’s album has eye-entrancing art by Steven Bradshaw that prompts you to question what you’re hearing on the album in the best possible way. The quiet wit of the “Wild Heart” cover makes it one of my all-time favorites.

At a few points, though, a media adviser would have done well to intervene. Yarborough’s monsters are indeed lovable; so the band’s name is a misnomer. Rick Fink has outgrown the name of his own label, which is Stoopid Brute Records. Then again, a media adviser might’ve told both guys not to make the records they wanted to make, which would be wrong.

Unlike traditional rock stars who are forced to live highly-protected lives, the ones next door can, in theory, be more readily contacted when you want to know what they were thinking. What does Rick Fink mean when he talks about somebody “smiling like a bishop in pickup truck”? Or Yarborough’s reference to Harry Truman? Well, my experience is that you’ll get an answer, but only one that shows how — in contrast to their classical counterparts — they work so intuitively that they aren’t obliged to explain. And one of the great functions that pop music plays in my predominantly classical life is not needing to know — or at least to verbalize — why I like it.