By the time he made his way to the podium, Leonard Bernstein was clearly in trouble.

Well after the entrance applause died down, he needed to compose himself, and he aggressively massaged his forehead just for a minute. But in stage-time, it seemed more like ten. He was about to begin a concert performance of Candide with the London Symphony Orchestra and an all-star cast. Would he make it through the next three hours? Given the uncertain delivery of his spoken introduction, would he make it through the next sentence?

This wasn’t just any Candide. The Voltaire-inspired 1956 musical had failed on Broadway but, like its picaresque hero who is batted around the globe by one calamity after another, the show kept reappearing in numerous revisions. For a few years, more music was written and added. By the early ’70s, Harold Prince and Stephen Sondheim had cut the politically-barbed satire into a sexy, farcical romp that Bernstein didn’t hesitate to describe as “a sliver” of Candide. At least that version kept the property alive — thanks also to the 1956 original cast album starring Barbara Cook that continually left listeners charmed, and also baffled that such a great score could’ve failed on Broadway. Of course, there had to be some mistake. (Barbara Cook told me the final performances had had people hanging from the rafters.) Was Candide kicked out of its theater because something more promising was on the way? (The culprit was said to be Lillian Hellman’s libretto. And it was. Having hunted it down, I found that it’s not only too clunky for the sparkling music, it’s downright pedestrian.)

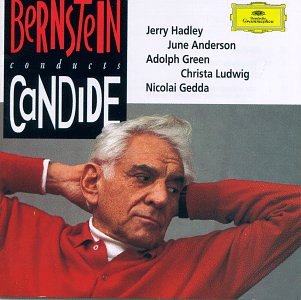

Bernstein’s December 1989 concert performances starring June Anderson, Jerry Hadley, Christa Ludwig, Nicolai Gedda and Kurt Ollmann — none of whom are still singing today — were his answer to the surprisingly numerous Candide-ologists, who had even analyzed the differences between stereo and mono “takes” on the original cast album. Bernstein incorporated pretty much everything he had written for the show over the years, as far as it made sense. That included both the songs Sondheim and Prince cannibalized for their versions and the songs that had been cannibalized. Spoken dialogue was replaced by narration. Those two live performances, at the Barbican in London, were videotaped, and in the first of those two, Bernstein looks healthier and more composed. A separate studio recording was made at Abbey Road. From there, Bernstein was to go on to a celebratory Beethoven 9th at the newly-fallen Berlin Wall that would be telecast around the world.

All of that happened, but just barely.

Candide was, and remains, a tall order, with its episodic narrative and cartoon-like characters that embody far more social and political significance than first meets the eye. In the forthcoming semi-staged performances by the Philadelphia Orchestra (June 20-22), Yannick Nezet-Seguin conducts what the publishers call the “2004 New York Philharmonic Edition,” which will be co-narrated by film and stage stars Bradley Cooper and Carey Mulligan. So you still don’t quite know what music you’re going to get in any given Candide performance.

But in 1989, the show existed in a much greater state of flux.

I arrived in London, on assignment from USA Today, in time for the second Barbican performance amid one of London’s worst flu epidemics in years. Key cast members had fallen sick. Replacements were flown in from Germany. In the video that edited together the two performances, you can see cast members changing from shot to shot. Leading lady June Anderson later told me that she had wanted to cancel but, in a phone conversation, Bernstein (also sick, and getting sicker) pleaded with her, saying “Don’t make me go out there alone!”

As usual, Bernstein rose to the occasion, drawing energy from the people around him, not to mention the effervescence of his own music. The performance wasn’t “another Bernstein triumph,” but it was more than respectable. At the later recording sessions, Bernstein seemed even less well. He turned up late, maybe by 15 minutes or so, but was still wasting what he knew was expense studio time. Key members of the cast, including Jerry Hadley and Christa Ludwig, were down for the count and overdubbed their parts months later. That was a red flag among those who knew Bernstein well. He was strictly against the artificiality of overdubbing. But he allowed it this time. Was something more than the flu going on?

It was often said that Bernstein was in a life-and-death race with himself, crossing the finish line with any given concert, piece, project or day, with life winning over death by a hair or two. He chain-smoked despite having emphysema for most of his adult life. He took uppers and downers, and drank seemingly constantly near the end. And he did so with complete awareness of what he was doing. “I smoke, I drink, I screw around,” he once told me. And shrugged.

Bernstein would lose that race some ten months later. A pleural tumor, diagnosed a few months after the Candide project, so deprived his brain of oxygen that, at his last concert, in late August of 1990 at Tanglewood, he couldn’t apprehend his piece Arias and Barcarolles well enough to conduct it himself, according to Jamie Bernstein in her book Famous Father Girl: A Memoir of Grown Up Bernstein. Bernstein wasn’t in anything close to that state for the Candide recording, but the fact that it was finished at all remains a minor miracle. Released after his death, it won a best-classical-album Grammy Award.

Still, listeners regard it with puzzlement. This sparkling operetta was treated to authoritatively slow tempos that accommodate large-voiced opera singers (as opposed to the more agile Broadway voices that had sung it before), often seeming so heavy-handed as to kill the show’s wit , or at least make it so arch as to lose its purpose.

Bernstein’s 1984 recording sessions of West Side Story with Kiri Te Kanawa and Jose Carreras revealed the pitfalls of casting international opera stars in Broadway roles. But just because operatic casting hadn’t worked didn’t mean it couldn’t work. Candide was more like European operetta than Broadway. June Anderson had dipped her toes into musical theater. Ditto for Jerry Hadley. Christa Ludwig had brought down the house with “I Am Easily Assimilated” in a Bernstein gala at Tanglewood. Lyricist and comic performer Adolph Green — Bernstein’s long-ago summer camp buddy — was Dr. Pangloss. Veteran tenor Nicolai Gedda was the South American governor. And, even in the face of a flu epidemic, how could such as cast be re-assembled anytime in the next three years?

I wouldn’t have blamed Bernstein for cancelling the interview I had scheduled at the Savoy Hotel prior to one of the Abbey Road sessions. Yet his hotel suite had a studied sense of normality. He was still in his bathrobe, looking worse than ever, sipping from a glass with a few ice cubes and medium-brown liquid. Conductor John Mauceri and his family had been by, and for them, Bernstein had ordered high tea with mountains of butter and scones. Personal assistants were on the phone arranging this and that. Yet to come was a audition/visit from Dmitri Hvorostovsky, who had just seized London with a Wigmore Hall recital debut with all of the charisma and artistry that was to make him a major opera star.

Interviewing Bernstein was an occasion for immense trepidation: you never knew what side of him you’d get. I first met him in 1983 in a hotel elevator in Ann Arbor. We were both going to the same concert — he conducting, I reviewing — and he offered me a lift in his limo. “Nobody here but us chickens!” he said. “I haven’t been a chicken in years,” I replied. “Don’t worry,” he said, “we’re all chicken at heart.”

Wow, a triple entendre. Then we talked politics.

In more formal interview settings, you could walk in with the greatest questions ever asked, and what you got was what was on Bernstein’s mind that day. Like the intricacies of symphony orchestra politics in the 1940 (interesting but not usable). Or how much he missed his late wife Felicia (very sad and usable). Once, when I finally asked a question he responded to, he said, “In what language do you want the answer?” At my wit’s end, I nearly begged for plain English. Earlier, over dinner that night, when he asked why I was picking at my stuffed crab, I explained that I was a vegetarian. “Why didn’t you tell the cook?” he asked. “I didn’t think to,” I said. Bernstein’s reply: “You asshole!” That was hard to process.

No games that day at the Savoy. Bernstein wanted to explain why he was changing a few words of text in Beethoven’s 9th to suit the fall of the Berlin Wall. He found fun parallels between Candide and Beethoven: Both had calamities every five minutes. He wondered if this expanded version of Candide could ever be convincingly staged; maybe it was best presented in concert with narration. But Bernstein also marveled at how the music had a consistent personality despite having been written over so many decades.

He applauded Stephen Sondheim’s courage with what was then his new off-Broadway show Assassins and jokingly referred to Philip Glass as Philip Plastic. He revealed that he came up with a great idea for fixing his failed 1976 musical 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, jotted it down on the back of an envelope, lost the envelope for a year or two, found it again and was now keeping it in a safe place. (After he died, his assistants tore apart his office looking for that envelope and failed to find it. Maybe it never existed.) Soon, we were in his limo making our way to Abbey Road studios. This was the first time I’d ever enjoyed his company. As we were climbing out of the car, he kissed me on the cheek and said “I LIKE you!” Now that was a compliment. Bernstein loved everybody in theory; being liked was more rare.

Once in the recording studio, Bernstein was mentally present but so ill he was having trouble staying vertical. The first order of these evening sessions was the complex, choral-dominated Auto-de-Fe scene. The London Symphony Chorus seemed too big and unwieldy for the assignment (as were so many things in this project). Yet Bernstein worked and worked hard. Finally getting a good take, he turned around to the engineers. No, it had to be done again. Clearly annoyed, Bernstein looked at the chorus and said “What do I know? I just work here!”

The “Oh Happy We” duet was a solo for June Anderson, with Bernstein mouthing the words for the absent Hadley. Nicolai Gedda was on hand for “My Love.” Though in his mid 60s, he sailed up to the high notes as if they were the easiest things in the world. Though he was Swedish, his English diction was excellent. When I asked him how he accomplished it, he said, “Oh, I just worked very very hard.” Like most comedians, Adolph Green was serious and reserved when not being Dr. Pangloss. He seemed to make a point of calling Bernstein “Leonard,” as if to remind you that he knew Lenny before he was Lenny.

Then came a bombshell. Bernstein’s super-savvy business manager Harry Kraut asked if I would like to come along to Berlin after the Candide sessions and write a short book about the Beethoven 9th at the Berlin Wall. Would I be willing to cancel my Christmas plans?

This was the break that I had been waiting for, and I was more than ready, having done journeymen years in Muncie, Indiana and Rochester, New York. USA Today was a great gig — how many newspapers send you to London to report on Leonard Bernstein recording Candide? — but a bit of a gilded cage. In the 1980s, “The Nation’s Newspaper” Today didn’t get a lot of respect in the industry. At journalism conventions and conferences, I was radioactive. Even those who knew my value didn’t think I could write anything of length. A book about Bernstein at the Berlin Wall would’ve been a high-profile calling card that would easily contradict that. For ethical reasons, I insisted on paying my travel and hotel expenses, even though I had no idea where I’d get that kind of money. Bernstein existed several decimal points away from my journalist’s salary.

Calling home to New York to share the good news, I found that spirits on the other end weren’t good at all. My partner, Garrett Cane, had been HIV-positive for years, and at that point in the epidemic, nobody knew much about life expectancy or treatments. His blood work had come back looking questionable and his doctor wanted to put him on AZT, the only treatment at that time and a highly toxic drug with unpredictable side effects. Garrett didn’t tell me to come home but it was clear that was what he wanted.

As someone who was HIV-negative, not yet 40 and looking to the future, I was in a quandary. Alison Ames, a top Deutsche Grammophon executive I knew from the New York office, gave me the most sensible advice: Find a support group. I did, at a gay community center that afternoon in East London, not a nice part of town. When I arrived, I was first buzzed in by intercom and the found myself facing a thick glass window and yet another maximum-security locked door. Clearly, this was to prevent gay bashing. I didn’t know if this felt more like a lock-down psych-ward or the county jail.

The group was maybe six people in a circle, most of them with tattoos (before they were fashionable) and missing teeth. We took turns talking. When my turn came last, any cultural difference between us melted amid the emotional gravity of what I was feeling. After I stated my case, the man sitting directly across looked at me intensely and said, very quietly, “I think he needs you.” At that point, there was no question: I was going home as soon as I finished my professional obligations in London. When I called to tell Garrett, he wept. Me too.

Harry Kraut was fine with my decision. Any New York person involved with the performing arts had some sort of AIDS-related situation in their lives. And the money I would’ve spent in Berlin might be money we would need for, well, more important matters.

I often wondered what might’ve happened had I gone to Berlin. But I never regretted the decision. AZT turned into a nightmare; Garrett couldn’t tolerate it at all. But at least I was there. He lived for another seven years.

Even as Bernstein became undeniably ill in the coming months — still somehow giving some great concerts — nobody believed he was dying. Impossible. Even after he had conducted what would be his last concert in Tanglewood, his press agent, Maggie Carson, called me to ask if I was available to interview him for forthcoming activities in the coming season, which included some unusual repertoire such as Mendelssohn’s Elijah. Soon after, Bernstein’s retirement from public conducting was announced, though lots of recording plans were mentioned, even Britten’s Peter Grimes. Who knows how real those plans were. And then, one day, Bernstein was gone. And New York was suddenly a smaller city.

When the Candide recording came out, I more than agreed with him about the score’s consistent personality. There’s a part of me that wouldn’t be without any of it, especially “Nothing More Than This,” an 11 o’clock ballad that Candide sings that becomes a brilliant emotional transition from the ultimate disillusionment and corruption of the characters into a new world of self-honesty with the finale, “Make Our Garden Grow.”

Generally, the score is one melodic miracle after another. Years later, the lead lyricist of Candide, Richard Wilbur, told me that Bernstein was driving him home one night after a work session when something by Saint-Saëns came on the radio. “Oh no!” yelled Bernstein, “I stole that one too! Sometimes I think I only have 12 melodies of my own.” Not true, of course, but if it is true, all 12 are in Candide.

I was amazed at how Hadley and Anderson had delivered some of the best singing of their careers. Keep in mind, this was before the Kelli O’Hara school of more dimensional Broadway acting. But I could hear the difference between the in-person chemistry of Anderson and Hadley, who overdubbed months later, attempting to take cues from in-studio videos taken of Bernstein at the time. That didn’t work well.

Anderson went on to sing for a number of years more but often seemed unconvinced by hardcore opera repertoire. She told me that Lenny had taught her how to be vulgar in a subtle way; it’s hard to turn back from that. Hadley tried numerous cross-over recordings with RCA; nothing worked, and his opera career declined. Friends of his were vaguely warned not to visit him backstage anymore. Sunny, smiling Jerry Hadley from Peoria, Illinois beat a drunken driving rap, and then, some time later, shot himself.

Christa Ludwig gracefully faded into retirement, singing splendidly, even in her farewell recital in New York. Kurt Ollmann took a faculty position in his native Wisconsin, and, according to Wikipedia, now lives in Savannah, Georgia. Adolph Green had a last blaze of glory with Betty Comden, writing the delightful Broadway musical Will Rogers Follies. I remember their lovely lyric for the show’s wedding song: “No shy violet, let’s middle-aisle it.”

Lenny stops by to visit periodically from the other side; the Bernsteins seem to be Olympic gold-medal haunters. His wife Felicia is spotted working out in the garden at the summer home in Fairfield, Connecticut so often that it’s not even considered unusual. And Lenny seems to be stomping around in an unprecedented dimension that he probably created for himself out of sheer will power. When I was at Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn doing a story on concerts held at the crypt. I found his low-key grave, where he was buried with his favorite book, Alice in Wonderland. “Okay, Lenny,” I said out loud, “whaddya want me to write about?” The gruff answer: “1600 Pennsylvania Avenue”. So I did. It’s still considered a lost cause. (Gore Vidal once told Bernstein to take the score to the Shrine of Lourdes, because it needed a miracle.)

Well, I tried. And Lenny hasn’t called me an asshole. At least lately.

My God! David that is one terrific piece – very moving and revelatory of what was not “officially known” about Bernstein and his last months of life. Besides, your insights are so valuable. Thank you.

Thanks very very much. I really didn’t know if i should write or publish this….

Will you be reviewing The Philadelphia Orchestra performances with Yannick, Bradley Cooper, et.al.for Inquirer.com?

I will be reviewing. That’s the occasion that prompted me to write this piece.

Very beautiful and brilliant. I hope I’m able to remember every detail of this. Otherwise, I’m going to have to bookmark it forever. Historians of the future will thank you, and so do I.

A bit of confusion in this passage: “By the early ’70s, Harold Prince and Stephen Sondheim had cut the politically-barbed satire into a sexy, farcical romp that Bernstein didn’t hesitate to describe as ‘a sliver’ of Candide. At least that version kept the property alive — thanks in part to an original cast album starring Barbara Cook…”

This makes it sound like Barbara Cook was in the cast of the 70s version of “Candide.” Not so: Cook starred in the original 1956 Broadway production. Harold Prince’s reworked revival that ran 1973-76 (first off-Broadway, then on Broadway) starred Maureen Brennan as Cunegonde. (And yes, it’s the 1956 recording that kept interest high in Bernstein’s brilliant work.)

A remarkable, beautiful piece, handsomely put together and written, as usual. One rarely gets personal insights into either a titan like Bernstein or the not-very-humdrum life of a fine music journalist.

Fantastic piece! It answers so many questions I’ve had for years. I read Jamie Bernstein’s book when it first came out, but it really didn’t answer what happened with Candide.

Thank you.

Thanks! I don’t remember seeing any family at Candide. They may have been paving the way for his arrival in Berlin….

When Theater Group director Gordon Davidson staged a scaled-down version of “Candide” at UCLA, featuring Carol O’Connor, in early 1967, he reinserted the song, “Nothing More Than This,” which had been omitted from the musical’s Broadway run because the show’s producers felt the play was running too long. It was a critical omission, like omitting the “Put out the light” scene in “Othello” or any number of other key speeches in great tragedies and dramas where the lead character has a moment of penetrating self-recognition before mayhem ensues. That song causes Cunegonde to follow Candide back to Westphalia with the recognition that he’s been her true love all along, and all the luxury and high times just an expensive waste of time and soul. Without that song, the leads are just dumb clucks marching along to a grand finale. With it, that finale rips your heart out with the realization of how much pain and waste often accompany the road to fulfillment, peace, tranquillity, love and joy.

Dorothy Chandler, wife of Los Angeles Times publisher Norman Chandler and one of the most powerful philanthropists in America, saw the show and three weeks later hired Davidson to run the Mark Taper Forum, the last architectural piece of the Los Angeles Music Center, thus projecting Los Angeles onto the world stage and the Taper into one of the most vibrant theaters in the country, responsible for, among other productions, “Angels in America.”

I agree that, in terms of the emotional and narrative arc, “Nothing More Than This” is critical and, I believe, top-drawer Bernstein.

But I can also see the other side, that in terms of pacing, that’s not what the show needs at that point. I say include it ANYWAY.

btw…at what point were all of those chorales written? Were they ever performed before that last Bernstein recording?