David Lang’s music is too pleasurable to be called experimental. Though his language takes the minimalist aesthetic to a very personal place — the little match girl passion being a prime example — it’s the message, not the music, that may make some listeners uncomfortable. As much as his new opera prisoner of the state feels like a major stylistic move toward mainstream tonality, it’s a continuation of his fusing of the message with music that best conveys it.

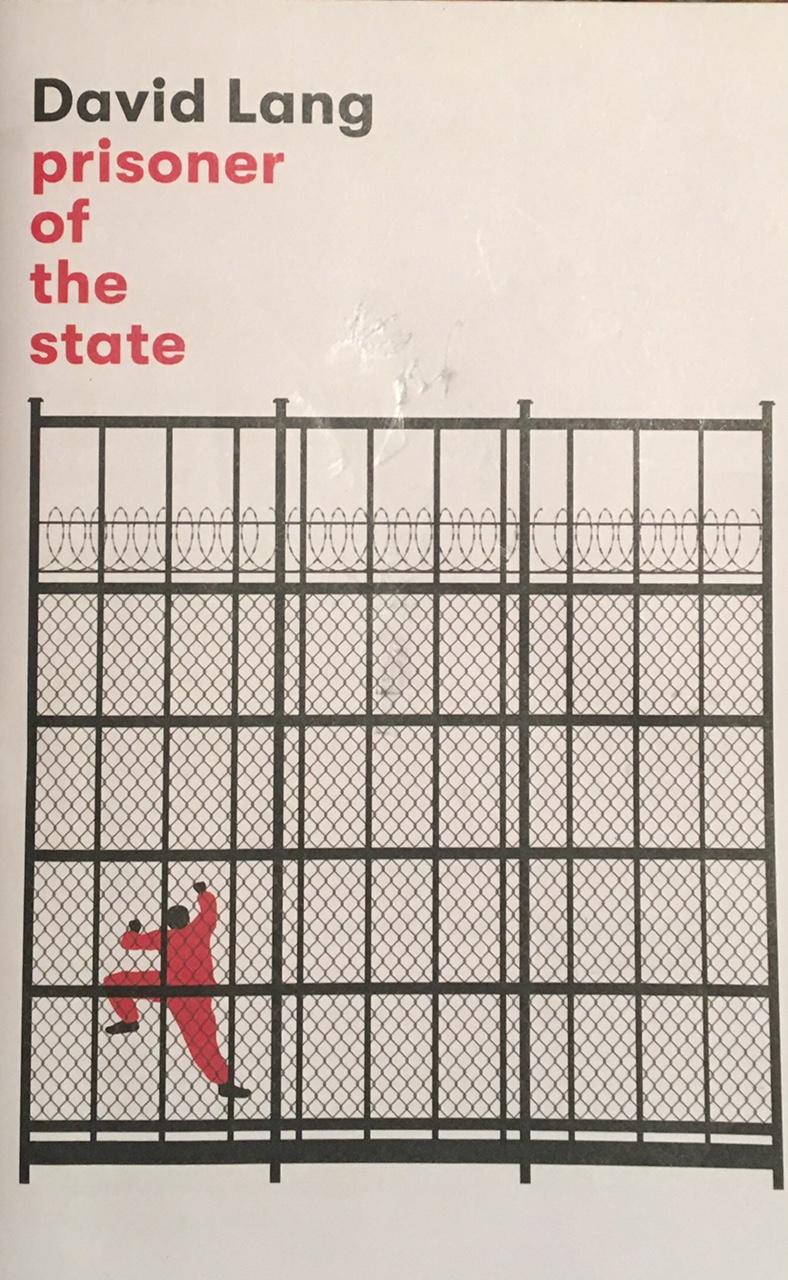

Premiered June 6-8 in a more-than-semi-staged version by the New York Philharmonic In David Geffen Hall at Lincoln Center, prisoner of the state is Lang’s response to Beethoven’s politically earnest but dramatically hobbled Fidelio, and emerged as one of his best pieces.

The opera was the finale of a mini-festival called “Music of Conscience” that capped Jaap van Zweden’s distinguished first-season commitment to truly new music. Earlier in the year, van Zweden premiered the hugely successful fire in my mouth by Lang’s Bang on a Can co-founder Julia Wolfe. And what led up to prisoner of the state for Lang was a series of extremely daring works that were probably artistic blind alleys, such as the 2016 Anatomy Theater (reviving a practice of holding public autopsies of convicted criminals) and 2018’s The Mile-Long Opera, written with individual singers stationed every ten feet or so along New York’s outdoor High Line singing fragments of text.

Prisoner of the state both rebels against and gets to the heart of Fidelio. It doesn’t bother with the subplot in which Rocco-the-jailer’s daughter falls in love with in-male-drag Leonore, who is only trying to rescue her imprisoned husband. Lang has characters step in and out of the narrative not so much to explain themselves as to reveal their place in the world. The Jailer (here without a first name, like all of the work’s characters) isn’t a naive accomplice to the starvation of political prisoners; he is doing his job, with full awareness of what his job is and that he exists under surveillance.

Unlike Beethoven, Lang asks why the prisoners are there. And in that great Bang on a Can tradition of singing in lists — another aspect of their distinct brand of minimalism — they state their crimes, evenly balanced between misdemeanors and felonies, giving detailed humanity to what would otherwise be an anonymous sea of blandly dressed chorus singers. Unlike in the little match girl passion, the word settings don’t crowd or get in the way of each other, and certainly don’t obscure meaning; this time, Lang wants to be heard in no uncertain terms.

Though his level of artistic integrity has never been higher than in this piece, Lang has never been less artsy. He’s angry and he’s serious. Here in the 21st century, we’re back to being outraged by suppression of liberty on many fronts. And if there’s one musical element that says so, it’s the stabbing rhythms (like something out of Stravinsky’s Symphony in Three Movements) that recur at dramatically appropriate moments.

Yet there are a few moments of tenderness. One is the confessional aria for The Assistant (the Leonore-as-Fidelio character), “I Was a Woman”, built on a few recurring motifs with isolated notes of piano accompaniment. Another is the brief but powerful duo in which the Prisoner’s dungeon cell (a cramped compartment under the floor of David Geffen Hall’s stage) and The Assistant stretches her hand down to him.

Though the opera is linear, the narrative is a series of set pieces that touch base with key parts of the Beethoven original. With none of the characters having specific names — they’re simply called The Jailer, The Assistant, The Prisoner, etc. — we don’t get the impression that this story is about any one hero or villain; it could be any of us. Lang’s minimalist sense, descended more from Louis Andriessen than from Philip Glass, provides for an orchestration allowing the New York Philharmonic to provide a textured bedrock for the story.

Lang’s vocal lines in prisoner of the state, often decorated with wind solos, are more long-breathed, more directed at tapping the emotion of the text, than the pithy cells of melody in the little match girl passion. The first-class cast — soprano Julie Mathevet, tenor Alan Oke, baritone Jarrett Ott and especially bass-baritone Eric Owens — made good use of them all.

This is one opera where the words are a bit more important than the music. And they’re bleak. Unlike Beethoven, the story doesn’t end with choruses of praise for the heroic housewife who saves her imprisoned husband from execution by a vindictive governor. It says that you can shoot tyrants all you want, but there will always be more, since Lang’s governor doesn’t really die. (As in Anatomy Theater, Lang’s characters have a way of singing after death.) The words of the final sermon — in emphatic, chordal word settings — say that we’re born free but all end up in chains, some of which are seen, some of which are not. This might seem some idealistic 1960s sentiment, though what these words provoke is an examination of the chains we choose for ourselves, sometimes happily, and those imposed on us by circumstance or accident. Some listeners say the opera didn’t earn this philosophical apotheosis. I say it did.

The “man behind the curtain,” so to speak, for prisoner of the state, as for The Mile-Long Opera, was Donald Nally, who prepared the prominent choral elements of each piece. This Philadelphia-and-Chicago-based chorus master has been instrumental (ahem) in transforming modern choral music with his Grammy Award-winning chamber choir The Crossing. This month The Crossing is venturing into semi-staged opera with Aniara: Fragments of Time and Space — not the 1959 Karl-Birger Blomdahl opera, but a new musical adaptation by Robert Maggio that’s also based on Harry Martinson’s sci-fi epic poem about a space ship fleeing the destroyed Earth but getting hopelessly (and existentially) blown off course en route to Mars. That’s June 20-23, 2019 at Christ Church Neighborhood House, Philadelphia, aniara.crossingchoir.org.