When music starts talking to you in plain English, what – if anything – are you supposed to learn? Imagine a brilliant, engaging lecture on the origins of species encased in an ongoing musical narrative and you have Scott Johnson’s Mind Out of Matter. Days after the premiere, I am still wondering what the piece wanted to give me, vs. what, in fact, I got.

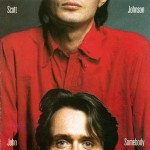

The aesthetic here isn’t pieces for narration and orchestra, but pre-recorded speech embedded into a musical composition – which clearly reached a new level the weekend of Oct. 5 at Montclair State University’s Peak Performances series with Mind Out of Matter. Steve Reich started that ball rolling with works such as It’s Gonna Rain (1965) in which snippets of recorded speech were looped and manipulated electronically to create a compelling, high-energy musical structure and narrative. But it was Scott Johnson who first used speech snippets as motivic kernels embedded into an instrumental texture, most famously in what many call his guitar symphony, John Somebody (1982).

Somewhat later, Reich’s Different Trains (1988) tended to be mistakenly credited with that innovation with its use of emblematic voices in a World War II triptych. Later, Reich took on the Biblical dawn of man with The Cave, which wasn’t overtly instructional, but took you to the source of the Middle East tensions that occasionally threaten to end the civilization that the warring tribes more or less began.

Johnson’s ambitions in Mind Out of Matter were more nuanced and comprehensive than those of The Cave. In John Somebody, the pre-recorded speech wasn’t informational, but was a poetic talisman that ran through the piece, mostly serving a musical function but sometimes creating a sense of being lost in modern life, as a female voice falteringly asked with interrogative inflections who is “John Somebody.” The central voice of Mind Out of Matter belongs to Darwinist Daniel C. Dennett, discussing how man’s domestication of certain beasts – cows, for example – has been an act of genetic engineering through natural selection, and then going on to show how philosophies and religions can undergo a similar evolution based on man’s needs.

Reading the program and the texts used in this accomplished seven-movement, 75-minute piece were essential to telling what was going on in the piece on a moment-to-moment basis, even though the electronic manipulation of Dennett’s voice was relatively light and at times helped articulate the ideas, particularly as he questioned and answered himself antiphonally though opposite speakers.

Using a palette of string, wind and brass sounds in an instrumentation rather like Aaron Copland original chamber orchestration for the Appalachian Spring ballet, Johnson’s rich, ever-fresh, never-routine musical responses didn’t dramatize the words – the closest instance being a wittily jumbled harpsichord that looped around a description of an ant climbing a blade of grass. Basically, Johnson energized the words, almost as if mirroring his own personal excitement at the discoveries he made when first digesting these provocative, beautifully expressed ides, and doing so with a huge variety of two to eight-note motifs.

I loved the “Winners” movement – about how information competes for space in our brains – partly because it was shorter on text than most movements and longer on music. In “Good for Itself,” a movement about how people tend to want to be good, the trumpet writing suggested was like one’s conscience delivering a warning against the rationalizations the get in the way of aspiring virtue. Some of the instrumentalists did double duty as singers in the chorale-like music that began the “Stewards” movement whose words said “deer are for deer, wolves are for wolves…sheep are for us….” A sardonic micro-fanfare accompanied a passage in the “Surrender” movement about religious ideas that are worth dying for. Why did rhythmic clapping accompany the “Awe” movement? Don’t know. But I liked it.

I wanted the piece to soar more, for the music to take the words on a wilder, bumpier ride. But that doesn’t mean I’m suggesting a revision. Music can accommodate information well; one could argue that the libretto to Verdi’s Falstaff is basically informational rather than poetic. But the heady content in the words of Mind Out of Matter seemed to hold the music back. Julia Wolfe’s recent choral work Anthracite Fields had a lot of information, including the endless names of injured coal miners, but left plenty of holes in the narrative, giving listeners room to enter the piece and connect the dots as they will. This seemed not to happen in Mind Out of Matter. Yet.

But this complaint could well be addressed not by the process that happens when performers live with a new piece for a while. On the surface, you couldn’t have wanted for anything better from the modern music ensemble Alarm Will Sound. But keep in mind that most if not all first performances involve a certain amount of cognitive struggle even when the notes are in the right places. And certainly, most premieres don’t rock out the way I think Mind Out of Matter wants to in any number of spots. So the jury, for me, is still out on this piece. But the question is not if the piece is important or substantial – it is, unquestionably – but how much it stands to participate in the larger process of cultural evolution that the piece itself so well describes.

[…] Scott Johnson’s Mind Out of Matter: Should music make so much sense?AJBlog: Condemned to Music […]