The tireless, ageless and ubiquitous conductor Rafael Fruhbeck de Burgos is suddenly no longer with us. His death at age 80 from cancer was announced on June 11 – only a week or so after he cancelled all conducting engagements. At that time, one could hope that it was a false alarm, that he was doing the right thing by letting orchestras know that there’s trouble, thus avoiding last-minute cancellations amid unrealistic recovery hopes.

Fruhbeck was no stranger to illness in recent years, yet maintained the frequen t-flyer miles of a man half his age, and even seemed outwardly casual about health concerns. After one illness, he was visibly aged but was even known to show his surgery scars to curious musicians among the many orchestras that he conducted. Now, one must stand back and look at what made him a great artist, but such an exemplary figure on the classical music landscape.

t-flyer miles of a man half his age, and even seemed outwardly casual about health concerns. After one illness, he was visibly aged but was even known to show his surgery scars to curious musicians among the many orchestras that he conducted. Now, one must stand back and look at what made him a great artist, but such an exemplary figure on the classical music landscape.

Outwardly, his recording output has been spotty for decades. Try finding his face on an album cover: It’s nearly impossible. No complete Beethoven symphony sets by him clutter one’s shelves or iPods. Yet Philadelphia Orchestra musicians came out of retirement to play Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5 under him – and say it’s one of the very greatest performances of that well-worn masterpiece they’ve ever played.

Every generation has a few senior conductors who prefer freelance to time-consuming permanent posts, often maintaining or shoring up standards among orchestras when their music directors are away. Past generations were treated to the aging Erich Leinsdorf, but I don’t think any players came out of retirement for him. But unlike Herbert Blomstedt, who conducts ultra-deep repertoire with only the best orchestras, Fruhbeck habitually went where he was most needed, and that’s with less-than-blue-chip orchestras, often with programs of works that audiences love to hear but other conductors avoid because they’re too warhorse-y.

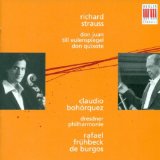

Though a favorite in Boston and Philadelphia, his name also turned up in Sao Paulo, Detroit, Cincinnati and the second-tier orchestras of Berlin and Dresden. He seems to be happily typecast in Spanish repertoire by Falla and Rodrigo, but he was also one of the world’s greatest conductors of Respighi tone poems and Scheherazade. Such works never sound like an obligation with him. Also, this specialty isn’t a compensation for deficits on the Austrian/Germanic front.

The Dresden Philharmonic (where he was music director in the mid-2000s) allowed him to record Brahms and Bruckner in wonderfully considered performances enhanced by the Spanish heart that he brings to his native repertoire. The final moments of the Brahms Symphony No. 3 are particularly magical in his hands. Some musicians called him “old school” in the best possible way, in his ability to take time in a piece without it dragging. His hugely interesting Dvorak Symphony No. 8 with the Swedish Radio Orchestra in 2011 had a grand sense of rhetoric (almost in the Furtwangler zone) that never turns inappropriately weighty. He wasn’t one to wear his wisdom on his sleeve. But it was definitely there.

Who knows what would’ve come out of his Danish National Symphony Orchestra principal conductor appointment (he was contracted through 2015 but resigned shortly before his death). The prospect of his Iberian coloristic sense applied to symphonies such as Nielsen’s 4th and 5th could write a new chapter in the performance histories of those pieces. And maybe he actually did so: Stay tuned to You Tube to see what European radio recordings of his turn up in the wake of his death. In any case, I’ll always remember him urbanely toddling onto the stage looking tan and fit, as if he just came back from a week in Monte Carlo, and making whatever orchestra he was conducting sound much the same way.

Fruhbeck conducted several concerts over recent years here in St. Louis (less than blue chip?), after a long absence. The musicians here totally adored him, and appreciated just how much he was from the ‘old school’. I managed to catch one of each his concerts here in those recent years. The last one was the week before his final concerts ever in DC, where here, it was the Verdi ‘Requiem’, with 4 soloists new to St. Louis. One interesting touch was that in the unaccompanied choral passage, he handed his baton to the tenor soloist, and led the chorus with just his hands.