Though I typically love Washington Post music critic Anne  Midgette’s reasoning and writing, her March 14 column on whether classical musicians should take political stands – forcefully argued and written – is deeply disturbing from the first sentence.

Midgette’s reasoning and writing, her March 14 column on whether classical musicians should take political stands – forcefully argued and written – is deeply disturbing from the first sentence.

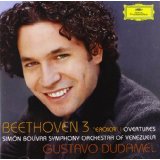

Midgette thoughtfully examines the public roles of musicians, asking if they have a duty to speak up for human rights, particularly when the countries that nurtured them are in significant turmoil. For Los Angeles Philharmonic music director Gustavo Dudamel, it’s the uprising against the current regime in Venezuela. With conductor Valery Gergiev, it’s Russia.

Her piece begins as follows:

“There’s a myth, in the popular imagination, that classical music is higher, better and more exalted than much of the rest of life.”

Myth?

Having lived and worked in Washington, D.C., I know that those who champion the fine arts there are always under the shadow of the anti-elitism police – we all know we they are – and thus tend to head them off at the pass, so to speak, with self-deprecating lip service.

If the value of classical music is a myth, why do we fund it – with ticket sales, foundation grants and, most of all, with our hearts – despite its flagrant lack of practicality? Broadway shows can barely muster much semblance of a pit orchestra. But Mahler symphonies, say, are played by a group of 100 or more. Surely, there must be some justification for that. And there is. It is higher, better and more exalted than much of the rest of life. If that’s not true, then many intelligent people have been utter fools for a very long time.

The argument over whether classical music makes us better human beings is the way of madness.Even the greatest people, whether involved with music or not, have feet of clay. It’s our nature. And who is anybody to chart another human being’s self-improvement at the hands of any artform?

As for the musicians themselves, Midgette tends to discuss them collectively, even though they occupy hugely different places on the chess board.

Those who create art are most notable for their inner lives, which intersect with their outer selves but exist in a distinctly different place. One has to hunt far and deeply to find expression of Wagner’s bigotry in his music, mainly in the finale of Die Meistersinger (when Hans Sachs warns against outside influences polluting their art) and the implications of ethnic cleansing under the surface of Parsifal. I believe that Wagner’s bigotry wouldn’t be nearly the issue that it is now had his music not been co-opted by Nazi Germany. And that’s not his fault – though he was rather foolish to throw his anti-Semitic opinions about in public to begin with. A composer’s primary responsibility is to his or her inner (and inevitably private) self.

I never quite believed how different that inner self can be until having the privilege of meeting George Crumb, whose dream-like, nightmarish, explosive music is nothing like the man himself – a gentle, unassuming, quietly happy human being who jokes, “People are usually pretty disappointed when they meet me.”

Performing musicians, inevitably, are public people with great responsibilities to the institutions needed to bring music into being. Pianist Gabriela Montero, as an independent entity, has the luxury to criticize Venezuela’s government. Just suppose that Gustavo Dudamel followed her advice to speak out. How much good would he do? What can he say that the politicians and human rights organizations have not? And how much harm might he cause? Speaking out could lead to the end of El Sistema, the musical education system that nurtured him.

What human rights organizations can’t do is perform Britten’s War Requiem. And that’s no small thing.

Though Gergiev has an international career, his energies have always been based in his Mariinsky Theater in St. Petersburg, which he has preserved and turned into an a world-class organization despite enormous odds. Whatever his true inner feelings might be, he is all but obliged to support Putin for the sake of his theater. Look at the chaotic Bolshoi Theater to see how bad the alternative can be.Where Gergiev crosses a line, for me, is endorsing specific policies, specifically what’s going down in Ukraine. That goes beyond merely protecting his institution.

Still, I can’t condemn him outright. One never knows what hidden reasons may compel him to conduct his public life in the way that he has.

I’m glad that Midgette brought up the cases of Germaine Lubin and Herbert von Karajan – two politically entrenched World War II musicians who had very different fates. Yes, Lubin performed in Nazi-occupied France, but did so for the sake of cutting back-room deals with the Nazis to win the freedom of various political prisoners. Lubin must’ve known she was putting her reputation in harm’s way. What she didn’t realize is that she would do jail time as a result. Karajan got off easy probably because he was then a small fish. That’s hard for us to imagine now. But de-Nazification appears to have been toughest not for the musicians whose hands were the dirtiest, but for those who were the most famous.

There’s always more to the story. And how often is there fairness in justice?

Therefore, I choose not to judge Gergiev. I do admit that my desire to access his art, whether in person or on CD, is greatly diminished. But isn’t that my personal matter?

The New York Philharmonic’s 2008 performance in North Korea is also discussed by Midgette. “A noble act of cultural diplomacy, or collusion with a bad regime?” Good question, and one that can also be lodged against orchestras who helped open up the People’s Republic of China to the West – and continue to tour there.

Classical music seems to be traveling through the Chinese public like wildfire – under a current government that has any number of questionable activities from a human rights standpoint. Not least is the forced re-engineering of Chinese society from rural areas to the endless fields of sterile high-rise apartment buildings in sprawling, hideously polluted metropolitan areas. One must see these terrains to believe them.

Amid this, are visiting Western orchestras wrong in trying to grab a piece of the Chinese pie while it lasts? What would be missing if they boycotted? The overall technical and cognitive level of Chinese classical music performance would no doubt suffer. One need only hear the labored recordings of Chinese orchestras before Mao’s Cultural Revolution to know that performance practice can’t exist in isolation. Also missing, should western orchestras boycott,is the life enhancement that even the wealthier Chinese now need more than ever amid their increasingly unlivable urban environments.

This is based on first-hand observation, not airy-fairy idealism: Chinese concert manners may not be the best, but one need only meet and talk to audiences to know what an impact Western classical music has on their lives.

Right and wrong do not exist here. What feels right at the point in time when any given decisions is made is what counts. And even then….

.