The first thing you learn about China is its vast number of rules – big and small, sensible and trivial.

The first thing you learn about China is its vast number of rules – big and small, sensible and trivial.

The second thing is that maybe 10 percent of the rules are enforced – though at any given time, you never know what 10 percent that will be. Or when.

Much later comes the more important realization: The people behind the rules have none at all. Books are edited and movies are banned with, apparently, no accountability.

Inside China, one hears cynical resignation; if the Chinese masses were ever infantilized Maoists, they don’t seem to be now. And the outside world, ever eager for a piece of the China pie, has few illusions about fair play along the Great Wall, but just has to hope for the best because the reward is tapping one of the largest and richest markets in the world.

But as Chinese artists are emerging in unprecedented numbers, can they thrive amid such shifting sands? The Russians more or less do – but that’s with the benefits of a centuries-old tradition. The Chinese have hit the ground running, with any number of rock-star-style role models such as pianist Lang Lang making it look easy.

What a different portrait emerged when the latest Robert Lepage theater piece, The Blue Dragon, played a short stint at the Brooklyn Academy of Music last month.

Contrary to those who only know Lepage from his Metropolitan Opera Ring cycle, the writer/director/filmmaker is viewed among his BAM public as something of a truth-teller who weaves together several stories happening in different times and places in mutually-revealing counterpoint.

The Blue Dragon piggybacks on one of the few major Lepage works I haven’t seen, the 1985 Dragon Trilogy. In this sequel of sorts, a French-Canadian artist, Pierre Lamontagne, has become a Shanghai gallery owner rather than pursuing his own art. He is presenting the brilliant young Chinese artist Xiao Ling, who happens to be his girlfriend and is slowly recognizing the seeds of her demise in her pregnancy.

Pierre’s alcoholic ex-wife Claire visits in an attempt to adopt a child and bonds with the girlfriend. The result is three typically Lepagian alternate endings. Other familiar tropes are from past works are people confronting the worse parts of themselves while traveling and children who enter the world lost before their lives even begin.

Not a lot of counterpoint in this one – but I brought my own, based on two weeks spent in China in June, a visit three years before, and a documentary film about Maoist China that disappeared from my luggage upon leaving the mainland.

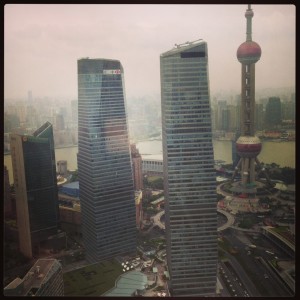

I seconded many of Lepage’s observations of modern Shanghai, starting with the abrupt re-engineering of humanity and the covert ways in which it’s accomplished. Lepage’s gallery owner is hindering one of many urban renewal projects that seem to arise on a daily basis in China that attempt to redraw the landscape in a matter of months in ways that would takes years, even decades, anyplace else. Indeed, the gallery is physically in the way, and when Pierre refuses to move, he isn’t invaded by the Red Guards or anything, but he finds that his heat, water and other essential utilities are coming and going arbitrarily. When he finally vacates, he discovers the government project he for which he is making way has radically morphed even before the original plans have been realized.

The big heartbreak is what happens to these people’s insides. A few years after Xiao has a triumphant exhibit, she has given birth out of wedlock, which can cut out a lot of services and privileges in this socialist state; she’s reduced to turning out counterfeit van Gogh paintings at a rate of a dozen a day. The implications are chilling: first, that someone would do that with their talent, second, that the upper-class Chinese would acquire such things as they might a good pair of Gucci shoes. Irate and cold, she simply turns up the radio when her baby starts to cry.

None of Lepage’s story was farfetched. While I was traveling in June to an earthquake zone outside of Chengdu, our guides were two women who had grown up there. But the city has changed so quickly that even they couldn’t find my hotel. At one point, we saw it glittering in the nighttime landscape, but we couldn’t determine how to get there. The Chengdu that I had seen only three years before – one that seemed like three cities stacked on top of each other (two of those being Atlantic City) – apparently disappeared. And it was replaced by what? The New Century Global Centre, officially the largest building in the world, said to be the size of 16 stadiums in the West. Now the Chinese billionaire who built it has disappeared, thought to be detained by government investigators, and at last report (mid-September) has not resurfaced.

Well, he’s a big fish. Would the government bother with small-fry artists? Our Chengdu guides had participated in some environmental protests – not only regarding the air pollution (which keeps defying one’s imagination by getting worse) but the massive engineering projects such as the Three Gorges Dam that environmentalists think are destabilizing the subterranean landscape to the extent of causing earthquakes and other natural disasters. These two women were mere faces in the crowd. But suddenly, they had no email for three days.

And then the Michelangelo Antonioni movie Chung Kuo China disappeared from my suitcase, though in a copy that carried a previous title, La Chine. Might that title still have been on an old list of forbidden films? When back in the U.S., I hunted down a copy under the Chung Kuo title, and saw an extremely flattering vision of 1972 pre-industrialized China.

Antonioni wasn’t about to be allowed to investigate the famines that occurred under Mao, not to mention the extremely talented classical musicians who died curing the Culture Revolution, if only because they were cultivated artists in Western music. The film certainly captures the natural ebullience of the people – and something more. They don’t pose for Antonioni’s camera, but probe it. As much as Mao tried to make everybody the same, every face in the film is that of an individual, and one whose interior wheels seem to be constantly turning. This is anything but a faceless nation.

The 21st-century Chinese seem eager to greet the future. You see it in the clerks at those sparking new high-end shopping malls – not-so-mini Fifth Avenues, you might say – that, as yet, seem to have very few customers. More curious are the endless landscapes of newly-built high-rise apartments, all of which are empty, no doubt awaiting the millions of people who are going to be moved from the country to the city by a government eager to maintain a high rate of economic growth.

What could all those people be feeling amid such quick and massive changes that even more-developed nations would find dizzying? Might such a society require the kind of emotional outlet that home-grown artists can supply?

To be continued.

As someone says during the Antonioni film, “You can depict a tiger’s skin but not its bones.” But even the skin will still tell you far more than you knew before.

Well, that’s what Communism does. It creates a lot of things people do not want (and over which they have no choice) and fails to create what they really do want and need. It’s perverse in that way. But as with postmodernism, which fails in exactly the same way, the one thing missing is – as you rightly hint – emotion. It’s because of a fear of emotion that such charades arise in the first place. But they should fool no one!

We stumbled over here from a different page and thought I may

as well check things out. I like what I see so now i

am following you. Look forward to checking out your

web page yet again.