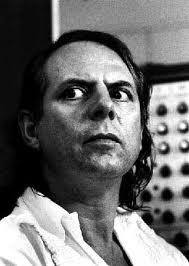

Karlheinz St ockhausen made it his business to be enigmatic – which is the core cause of his being modern music’s greatest public relations disaster. Long before he made his 9/11 gaffe (“And that is the greatest work of art that exists for the whole Cosmos”), long before he revealed that he had extra-terrestrial origins (he claimed to be from a planet orbiting the star Sirius), Stockhausen retreated from the public, all but posting no-trespassing signs on his work by withdrawing his extensive discography from conventional circulation and making it available only by mail order and for outrageous prices, and sometimes only to educational institutions..

ockhausen made it his business to be enigmatic – which is the core cause of his being modern music’s greatest public relations disaster. Long before he made his 9/11 gaffe (“And that is the greatest work of art that exists for the whole Cosmos”), long before he revealed that he had extra-terrestrial origins (he claimed to be from a planet orbiting the star Sirius), Stockhausen retreated from the public, all but posting no-trespassing signs on his work by withdrawing his extensive discography from conventional circulation and making it available only by mail order and for outrageous prices, and sometimes only to educational institutions..

Avant-gardists can be exhausting to their public, and Stockhausen was the most exhausting of them all. Witness Licht, his cycle of operas, one for each day of the week, that seemed beyond impossible in their demands.

Now, isolated scenes and acts from Licht are surfacing in the most visible of places. This summer’s London Proms presented the first scene of Mittwoch, performed not by an opera organization but a chorus from Birmingham, Ex Cathedra, directed by Jeffrey Skidmore. The late-night-at-the-Proms audience gave it a rock-star response. One of the great critical successes of the Lincoln Center Festival was Michaels Reise um Die Erde (Act II of Donnerstag) in a full production imported to Avery Fisher Hall with Ensemble musikFabrik. It was taut and electrifying.

Having studied the full Donnerstag in its Deutsche Grammophon recording and found it to be overwhelming and bewildering, I think further explorations into Licht (written over a 25-year period ending in 2003) may be best explored, for the time being, in this piecemeal fashion. Having seen Michaels Reise in person and only heard Mittwoch on the radio, I believe one crucial factor in appreciating these works may be encountering them in person.

One could argue that the Fura dels Baus Michaels Reise staging (directed by Carlus Pedrissa) could make anything riveting. The opera’s mythological scenario, in which Michael the Archangel circles the globe, battles with Lucifer and wins Eve, was realized through some spectacular computer graphics that truly gave a sense of circling the globe at warp speed. The digital imagery also support Stockhausen characters that, on their own, could feel like figures in a finger-wagging Bible story as opposed to something that tapped into deep human consciousness.

Here, operatic abstraction is achieved if only because  characters are portrayed as instruments, Michael being a trumpet and Eve a basset horn. This production had trumpeter Marco Blaauw attached to a crane, spinning and gyrating through the air while playing some pretty complex music. It’s hard to know how much Stockhausen’s trumpeter son Markus impacted the form and manner of Michael’s Reise since he was only 21 years old when the composer began writing the piece in 1978. I like to think that he did, coaxing his father out of his cosmic world to write for an instrument that all but insists that its jazz connections be acknowledged. One of my favorite parts of the opera was an extended duet between trumpet and pizzicato bass – a combination that could come straight from New Orleans.

characters are portrayed as instruments, Michael being a trumpet and Eve a basset horn. This production had trumpeter Marco Blaauw attached to a crane, spinning and gyrating through the air while playing some pretty complex music. It’s hard to know how much Stockhausen’s trumpeter son Markus impacted the form and manner of Michael’s Reise since he was only 21 years old when the composer began writing the piece in 1978. I like to think that he did, coaxing his father out of his cosmic world to write for an instrument that all but insists that its jazz connections be acknowledged. One of my favorite parts of the opera was an extended duet between trumpet and pizzicato bass – a combination that could come straight from New Orleans.

Much of the music achieved aria-like effects by having the soloists play rhapsodic lines over extended pedal points (or long-held tone-cluster chords that functioned like pedal points). I could connect with the music in ways that I seldom have with Stockhausen, who can juxtapose so many elements at once that they cancel out each other’s visceral impact. Michaels Reise was not one of the composer’s sonic circuses (that some might call a freak show) for which even a wide frame of musical reference is no help for fathoming the meaning at hand.

Sometimes I wonder if knowing any given Stockhausen piece helps to fathom anything else in his output. Yes, I’m a Stockhausen skeptic. Though I respect his industry in writing seven huge operas for the days of the week, I left the New York Philharmonic’s performances of Gruppen last spring convinced that it was “augenmusik“: With its complete lack of sensuality, the piece seemed best understood by reading the score rather than hearing it. This is not a good thing, IMHO, though I remain open to argument.

The case for hearing Stockhausen in person was bolstered by the Mittwoch broadcast from the BBC Proms. Given how much individual singers received separate applause, there was no doubt a level of characterization – in this portrayal of an international conference table as a Tower of Babel – that was lost on those who weren’t at Royal Albert Hall. The density of Stockhausen’s textures – which is partly what makes me think he was writing “augenmusik” – is such that the Tower of Babel’s controlled chaos doesn’t come through nearly as much as in Berio’s Sinfonia (second movement). But more than, say, Gruppen, Mittwoch has some arresting moments that feel like prayers and chanting of a certain perverse sort, as well as long held contemplative notes that seemed like pedal points with nothing to anchor.

Stockhausen’s music so often pulls the rug out from under his listeners. You can approach his music ready for anything and everything – and then he re-defines anything and everything, often giving you sounds you didn’t expect because you hadn’t yet imagined them, or by subtracting an element of music that previously seemed essential. In any case, Stockhausen’s Licht perhaps needs to be seen to be believed. Perhaps these concerts of discrete excerpts are laying the groundwork for that.

I caught that BBC Proms performance of “Welt-Parlament” (hope I got the spelling correct) on iPlayer, as well as the first work, “Gesang der Junglinge”. I certainly don’t claim to “get” Stockhausen after just those pieces, but at least I have a better sense of his imagination at work.