Rarely pleasant and all-too-familiar, stumbling blindly into uncertain darkness – whether bicycling down a nighttime country road or solving a near-impossible problem – is an accepted fact of adult life.

Rarely pleasant and all-too-familiar, stumbling blindly into uncertain darkness – whether bicycling down a nighttime country road or solving a near-impossible problem – is an accepted fact of adult life.

But not everybody wants to attend an opera that embraces that condition – starting with the blindfolds that audiences were required to wear throughout The Blind, Lera Auerbach’s opera, developed by American Opera Projects and presented last week at the Lincoln Center Festival.

Lining up in the hallway leading to the Kaplan Penthouse, one had to check everything, don the white velcro blindfold, put your hands on the shoulders of the usher in front of you and be led, like Eurydice trailing after Orpheus, into a room where you’re seated in a particular chair.

Enigmatic things were whispered in my ear. Sound effects of howling wind and a single crying baby set the scene for the Maurice Maeterlinck story about a hapless flock of blind people on a barren island who are led out of doors to enjoy the day’s waning sunlight, only to be abandoned by their priestly caretaker – who is later found dead. The blind stumble about the island, not knowing if it’s day or night. Only the baby among them can see, but is too young to provide any useful information – a theme also explored in that Belgian symbolist’s Pelleas et Melisande.

Written almost entirely for unaccompanied singers, Auerbach’s score has voices unmoored from the sort of pitch solidity offered by supporting instrumentalists. The music depicts individual blind persons at times, the mob mentality at others; there are atmospheric moments that suggest the windswept outer landscapes with dissonances conveying inner terror, relieved by the flickering hope inspired by smelling fragrant earth (whiffs of which are caught by the audience) but dashed by the onset of cold winds (which also sweep through the venue). Electronic effects include pounding footsteps as death approaches.

Critics haven’t exactly been kind; one trusts that negative reviews are most likely a simple matter of not having responded to the piece. But extreme reactions were anticipated even before the opening performance when, at a workshop held some months before in New York, some members of the invited audience of donors declared they’d rather leave than surrender their shoulder bags and other belongings (as required by the opera). The Blind presses buttons.

To suggest that your platinum credit card is your identity is not superficial: You’ve worked for the certainty it offers, the promise that you could be stranded in the wilds of Beijing and still find your way home. I’m told that one scenario common in the S&M community involves meeting a stranger you’ve only met online and immediately surrendering your wallet and car keys. That’s tough. Remember the words of Lily Tomlin, who once said that to be in New York City is to always know where your purse is.

Maybe you don’t know how much you’re going to rebel against the requirements of The Blind until you get there, even though Lincoln Center gave ample warning. The operator at Center Charge told me about the blindfolds twice. The day of the show, a message on my answering machine reminded me of these terms and conditions. Wearing the blindfold meant taking off your glasses. For the woman in line behind me, that meant giving up the very thing that, as a small girl, allowed her to apprehend what had previously been a blurry world.

My own trust issues are such that I wouldn’t set foot in the growing number of restaurants where you eat blindfolded. I will always want to see what I put in my mouth. But seemingly by accident, numerous personal experiences primed me for The Blind.

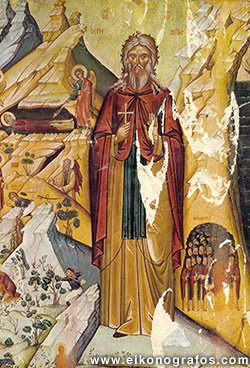

During my inverted childhood in the Illinois cornfields (sort of like My Fair Lady performed on the sets to Oklahoma!), I connected strongly with Pelleas et Melisande, whose characters didn’t know where they were or how they got there. Only weeks ago, I was hiking alone in southwestern Crete, and upon finding my way to the famously remote Cave of the 99 Priests, I realized that even my smartphone and platinum card would be no help if the aged ladders leading into the cave should fail.

The afternoon of The Blind, I saw Shun-kin, a Theatre du Complicite production (also part of Lincoln Center Festival) whose title character is a blind Japanese musician – her story told by her masochistic care-giver/lover. Both find freedom in blindness. The superior sensitivity and awareness that Shun-kin achieved from her blindness allow her to operate outside the usual rules of society, having numerous children out of wedlock (and thoughtlessly giving them away) and, at times, physically attacking students who don’t meet her standards. The caregiver/lover/narrator Sasuke (whose real-life writings are the basis of the play) blinds himself out of complete (or blind?) loyalty to Shun-kin. In contrast to her imperiousness, he discovers “paradise.” No longer does he trouble himself with the mundane temporal world.

Small comfort that would be to the denizens of The Blind. They’re out in the elements freezing to death.

In what has to be one of Maeterlinck’s most pessimistic and problematic plays, his characters aren’t allowed to touch each other – yet another manifestation of existential apartness, as if being blind weren’t enough.

As in much Maeterlinck, narrative barely exists. (That’s one reason why Pelleas once had a high walkout rate at the Metropolitan Opera.) Nothing much happens. Characters in The Blind are only momentarily individuated. We’re certainly not told their names or given any sort of external information (old, young, etc); we never learn how they came to be blind. Vocal lines are highly inflected. They bicker and rage, with an occasional reflective aria.

The sound palette vaguely resembles the choral writing in the hurricane scene of Porgy and Bess. I don’t think Auerbach was influenced by Gershwin, but she arrived in a similar terrain out of the necessity to create an emotionally appropriate vocal texture. That texture inevitably takes the form of vocal undulating, sighing and a sort of aleatoric mumbling suggesting people engaged in prayer – though not the same ones at the same time. “We are lost. There is no way out!” they sing. They would seem to be punished for existing. Yet at times their voices become the wind that is freezing them to death. Protagonist and antagonist are one in the same.

But the jury will be out on the score until it finds the right kind of performance. Though conducted by the superb choral director Julian Wachner, the 12-member cast consisted of fully operatic voices. Leaner voices would render the music less opaque; less heated delivery would allow the words to carry their own weight and not seem so bald from having been writ so large. I imagine The Blind reaching its potential not with an opera cast, but with one of the world’s super-choruses, such as the Latvian Radio Choir. The piece may need years to find its legs. When it does, I’m certain that it will be worth the work.

As it was, the performance, to its credit, dredged up lots of inner stuff. Nothing else I’ve ever experienced in the theater has made me so immediately homesick. I longed to be indoors (even though I was). Most terrifying was the end. When the opera concluded, nobody knew if it was over. We all sat in silence. It seemed the opera hadn’t merely ended, but decamped. I had been abandoned by The Blind. It took forever – forever – for somebody to announce that the piece had ended and that we could take off our blindfolds.

“Well, why didn’t you ask the baby if it was over?” asked one friend, not trying to be helpful.

“The baby couldn’t have been real. It was sampled!” I replied.

A French symbolist conversation indeed.

For the record, I checked with a production person who told me that “forever” had been exactly three minutes. What does that say about the hold this piece had over me?

This experiment reminds of The Blind Cafe, which has a bit more guidance and instruction to it and a great deal more education. It’s not a classical music presentation, but it does give a better presentation in general that leaves you feeling changed as a person in a good way.

Check it out: http://theblindcafe.com/