The scene was Carnegie Hall in the wake of a snow storm, roughly a decade ago. The Metropolitan Opera Orchestra under James Levine had just played a knockout performance of Carter’s Variations for Orchestra.

Months before, I had interview Carter in his Greenwich Village apartment a few weeks after the death of his wife. As one can imagine, he didn’t look so well. I worried that the still-earthy, hearty, unpretentious Carter would die soon, as so often happens when the elderly lose a longtime spouse. He related that he’d only lost a day of composing when she died. She would’ve wanted it that way.

Even in his somewhat dampened state, Carter conversations weren’t unlike listening to his music. Subjects ricocheted off each other. Everything ended in an exclamation point. Cul-de-sacs were accepted as part of life’s ongoing anti-logic. Non sequiturs were some of the more familiar objects on the landscape. You never, ever knew what lurked around the corner. So it wasn’t surprising that at the end of interview, we somehow got on the subject of Prokofiev operas.

Carter had seen the most obscure one of all, a socialist/realist something or other titled The Story of a Real Man, and in Germany, where the actual surviving war hero was present and seated in a box overlooking the stage. At the end, the audience wanted the hero to stand up and take a bow.

“But he couldn’t!” related Carter. “He was a double amputee!”

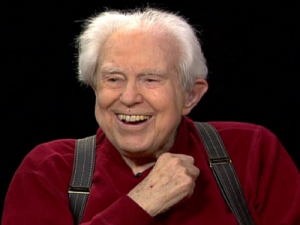

Back to Carnegie Hall: Carter had no such problems that Sunday afternoon. The 93-year-old composer navigated the stage more deftly than Levine. He didn’t look a day over 70. Seeing him at intermission, I practically threw my arms around him. “Elliott, you look wonderful!”

“Yeah, yeah!” he groused. “I wish I could hear as well I look!”

Classic Carter….

It’s interesting that the interview mentions Social Realism and how Carter’s music was almost the antithesis of that aesthetic philosophy. There seems to be a kind of ironic message in the fact that the hero can’t stand for a bow because he’s a double amputee – as if standing for principle ends in absurd folly.

Perhaps I see it that way because the USA once had a wonderful tradition of politically oriented art that McCarthyism largely suppressed during the 1950s through its harassment and black lists. The artists ranged from Arthur Miller to John Steinbeck. People were even driven to suicide.

And in the two decades that followed the CIA spent hundreds of millions of dollars to *secretly* promote abstract expressionism as a means of suppressing political art. The massive program was called The Congress for Cultural Freedom. It had offices in 35 countries and CIA agents infiltrated the boards of some of many of our most famous foundations and arts institutions like the Ford and Rockefeller Foundations and MOMA. They fronted numerous phony cultural magazines and even arts festivals. To this day, the USA is notable for its relative lack of political art compared to other Western democracies.

These two URLs contain useful information about the program:

http://monthlyreview.org/author/jamespetras

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Congress_for_Cultural_Freedom

Anyway, I know that in my disgust for this history I read too much into Carter’s comment, but it’s ironic to see one of the beneficiaries of this constructed history of de-politicized art make such a comment. Maybe its time for us to take a closer look at this history and discuss its implications. Yes, Carter and many of the composers of his time “embodied our inner and outer chaos”…as long as they didn’t challenge the political status quo with all of its racism, war, and economic injustice. There were a handful of exceptions, of course, but the general pattern of that constructed history is still with us.

Actually, I didn’t know that Mr. Carter had just died last night. Sad news.

What about pop music? Bob Dylan? Jefferson Airplane? Or George Crumb? All of which could be extremely political….

dps

Yes, pop music was often very political in the 60s and fueled the anti-war movement. Dylan was iconic in that regard. Odd that pop now seems so apolitical. Pop was not covered by the Congress for Cultrual Freedom. The CIA seemed to think that “musical intellectuals” were a more important target. (Big mistake!)

I recently read where someone said that the social content of pop was a mile wide and an inch deep. I’m not sure about that. I think people like John Lenin made some very important political statements. My favorite would be his song “Imagine” which has a kind of profound simplicity.

I studied with George Crumb and deeply admire his music, though I never thought of it as political. I’m really curious why you might think of it that way – if that’s what you meant. Perhaps there’s a dimension I have missed. Perhaps something in the late songs? I know that he’s an election night junkie and follows the whole evening with the keenest interest. So I figure I know what he’ll be doing tonight.

I had forgotten about Crumb’s “Black Angels” — a very effective anti-war statement.

That’s what I was thinking. One could argue, too, that any use of Lorca makes a political statement.

There’s also the anti-war sentiment in Crumb’s setting of “Johnny Comes Marching Home Again.” I know what you mean about Lorca, though I’ve never sensed Crumb was attracted to his poetry for political reasons.

In any case, discussion of the politics of abstract music is always almost impossible. Political meaning seems to be best analyzed in by studying the larger context in which the music is placed. It’s what Christopher Small refers to as musicking, an understanding of music as a ritual in social space. It is the conscious or unconscious supression of those meanings that seems to constitute the depolitization of classical music in America.

Mr. Osborne,

If you’re going to engage with new musicology’s penchant for conspiracy theories, instead of linking to a socialist website & a Wikipedia article, you ought to direct readers to one of the main defenses of this theory du jour — Richard Taruskin’s Oxford History of Western Music (http://www.worldcat.org/title/oxford-history-of-western-music/oclc/54679502&referer=brief_results). And to be fair to the unsuspecting readers who might be taken in by Taruskin, it would be good to also link to Charles Rosen’s answer to Taruskin on pp211-247 of his recent book, Freedom and the Arts (http://www.worldcat.org/title/freedom-and-the-arts-essays-on-music-and-literature/oclc/758383819&referer=brief_results)

There are two sides to this issue. For me, for what it’s worth, at the end of the day, The Taruskin position generally – and what you seem to be implying about Carter – is simply absurd.

Sorry Stephen, but your post in unclear. Which issue(s) do you think have another side? I’m not sure since I made several points in my post you could be referring to. That the CCF had a large impact on aesthetics in the 50s and 60s? (Some deny it. The CIA brags about it.) That highly abstract composers benefited from these efforts? That musical elitism reinforces the power structures of social and economic elitism? That devotion to the prevailing aesthetic by the musical elite suppressed the work of composers who refused to follow it? Which of these ideas does Taruskin advocate (and perhaps with some quotes since here in continental Europe people can’t run out and get his tome? I haven’t read it, though hope to some day.) I’ve seen few articles in the so-called new musicology about Carter, so which ones are you referring to? And it’s odd how little musicology has been written about the CCF. Many possible topics for interesting discussion, though I know that reasonable dialog can be difficult when people feel their musical idols have been tarnished. That was not my intention, so why not give it a try?

I admire Carter’s work. Of late I’ve been thinking about how he almsot self-consciously made an effort to sound modern, but that the traditional perspectives of his earlier period always lingered in his music. Perhaps it was that symbiosis that made his work so good, and generally superior to other “complex” composers who lacked that background.

Well, William, I have no idea where you’re living, but you can get access to both works I mentioned by going to the links I gave & poking in your location to find libraries in continental Europe that have copies. And the Rosen (which contains Taruskin quotes that Rosen takes issue with) isn’t expensive through Amazon if you’re interested enough in looking at other sides such that your own idols may take some tarnishing (& btw, I have idolized no one since Scott Nearing died).

I’m not going to do your reading for you. So I will ignore your Gish galloping questions, and cut right to the chase, which I apologize that I evidently didn’t make clear enough. My initial intent was just trying to offer a little balance for the benefit of the innocent reader that nothing in your story should be taken at face value – & then get out.

First, the only two sources you chose to list are not exactly something an intelligent reader would want to take to the bank. The reason I mentioned Taruskin & Rosen was to give readers, if not you, a way to get at more than the single viewpoint you offered — & actually I should not have said there are two sides here: it’s much more complex than that, in my opinion.

So since you seem interested, here’s what really got me started. You wrote:

“the USA once had a wonderful tradition of politically oriented art that McCarthyism largely suppressed during the 1950s through its harassment and black lists. ”

Well, that’s news for those out there who have never heard of HUAC. Unfortunately that number appears to be growing, so thanks for the reminder. But, “wonderful tradition of politically oriented art”??? Of course no responsible person would want – even if it were possible – to keep politics out of art (yes, we are social creatures, after all). But your phrasing belies an unrealistic nostalgia for something more — social realism. And by linking to James Petras’ truly weird diatribe, you have approved a brand of socialist realism that’s even more radically anti-modernist than the following which, surprisingly, was not written by John Adams:

“… the negation of basic principles of classical music, the preachment of atonality, dissonances and disharmony, supposedly representative of ‘progress’ and ‘modernism’ in the development of musical forms; the rejection of such all-important concepts of musical composition as melody, and the infatuation with the confused, neuropathological combinations which transform music into cacophony, into a chaotic agglomeration of sounds – [music] strongly reminiscent of the spirit of contemporary modernistic bourgeois music of Europe and America, reflecting the dissolution of bourgeois culture, a complete negation of musical art, its impasse.” From the February 1948 Resolution of the Central Committee of the Communist Party on Soviet musical policy (quoted by George Perle in The Listening Composer).

This could go on and on, back and forth. And that’s just the point. There’s no question that ol’ Joe & HUAC were a disaster for art in the United States & destroyed lives for political gain. But there is also no question that the other ol’ Joe & the Communist Party were a disaster for art in the Soviet Union & destroyed lives for political gain. The truly sad thing is that the names & terminology & geography & nationalities have all changed, but the same battle still rages. In the end, I can only turn to Shakespeare: “All are punished.”

Now, this is probably still unclear to you, but that’s it. Have your final say if you want it. ‘Cause I’m outta here.

I’m sorry that you are more interested in expressing condescending disdain than in dialog. Ironically, that is exactly what I’m talking about — a musical epoch that had a penchant for totalizing thought that marginalized those who disagreed and even viewed them as something like apostates unworthy of interaction. It was either their way or the highway. Thanks Stephen, for illustrating my point…

Note that Stephen lists no references from Taruskin. That’s because the actions of the CCF have hardly been examined by musicologists. In my view, this leaves a serious gap in our knowledge of post war music in America. One of the principle questions that needs to be answered is to what extent the CCF shaped American music. It spent uncountable millions, had offices in 35 countries, hosted international festivals, published numerous influential journals, and infiltrated the boards of many of our most important cultural institutions. And all was done secretly through false fronts. Why has this seemingly important topic been ignored by musicologists? Why does this important question meet with the sort of aggressive indignation and denial that Stephen illustrates?

It’s ironic that in a discussion of McCarthyism Stephen resorts to red baiting. No one should think that I extol Social Realism or Stalinism. They were horrific and greatly harmed the arts. My view is actually that the governments in both the East *and* West made conscious efforts to instrumentalize the arts and not always to their benefit. The common view in the USA is to suggest that only the Soviets meddled in the arts to significant effect.

Stephen is Senior Specialist for Contemporary Music in the Music Division of the Library of Congress. Perhaps his position shows the benefit of towing the line. I wonder to what extent his biases will shape what is archived and left as the record of what post war American music was, and the forces that shaped it. Something tells me he won’t want to talk about that either…

Just one other thought, Stephen. Reading between the lines I think you are associating me with the post-modern thought in new musicology and its manifestations in writers like Greg Sandow. Actually, I appreciate some of the things they do, but strongly object to a lot of their work. Here is an essay I wrote about some of the weaknesses in post modernism and their negative manifestations in new musicology:

http://www.osborne-conant.org/email2/pomo-weakening.htm

I also have other essays about the links between neo-liberalism and post-modernism in music that are even more critical.

Valuable information. Lucky me I found your web site by chance, and I’m shocked why this coincidence didn’t took place earlier! I bookmarked it.