The divine is insinuating itself into opera – and in doing so, is creating dramatic reversals of what certain kinds of music say and do.

Though gods and goddesses were onstage almost exclusively in Baroque opera, everybody knew they were just us in disguise – and in the real world

of church politics, they wouldn’t even rate the first stage of beatification, much less the canonization process that took poor Hildegard of Bingen something like 800 years to achieve.

Last weekend at Princeton’s McCarter Theater, American Opera Projects and Opera New Jersey presented Blessed Art Thou Among Women, an intriguing melding of two new operas: Our Lady with music by Gregory Spears and text by the 13th-century Guiraut Riquier, and The Wanton Sublime with music by Tarik O’Regan and a libretto by Anna Rabinowitz. In between was Vivaldi’s Stabat Mater – abbreviated.

The project hadn’t really settled in yet; value judgments on the new works and how they all fit together are best left for encounters when the performers have had a chance to live with the music and stage presentation. But these and a few other pieces that have come my way of late suggest that new creative responses toward religious iconography are afoot on the larger landscape. Though the church has centuries of great artistic history, we’ve been more likely to encounter the likes of Elijah or St. Paul in secular concert settings. Jesus Christ and the Blessed Virgin Mary have tended to stay in the church (or, in the concert hall, within the texts of the church’s liturgy), and portrayed under strictly prescribed circumstances.

Christian religious paintings were extremely stylized, and sometimes made according to such strict precepts that there was an enforced uniformity of expression. Similarly, Renaissance polyphony was not about projecting any individual expression of faith; it was more of a glorious groupthink that actually created a firm standard of quality control.

Even the popular Biblical epic films of the 1950s and ’60s were careful about dealing with Jesus. His most effective Hollywood appearance, perhaps, was in Ben-Hur: When Charlton Heston is working on a chain gang, a mysterious figure appears to give him water, is only seen from the back, says not a word, and has a drinking gourd that never runs dry. We’re never told it’s Jesus, but the awed reactions from the normally cruel guards leave no doubt.

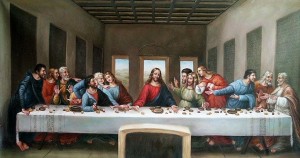

Of late, I’ve stumbled upon a live recording floating around the Web of The Last Supper by that paragon of unrepentant British modernistic severity, Harrison Birtwistle, from the 2001 Glyndebourne Festival season. Birtwistle rarely fails to knock me sideways (in the best possible way), but this piece seems to be particularly courageous. Christ’s farewell dinner emerges, at least to my ears, as something of a rip in the fabric of the universe – such a fundamental sea change in human existence, one so abrupt and occurring at a single point in history, that the event seems far more traumatic than ecstatic.

The opera achieves this with static, atonal sonorities that come from nowhere and lead to nothing – at least in terms of my musical points of reference. It’s creepy and terrifying. And maybe never have I heard music give such a realistic portrayal of faith. Christ’s followers are witnessing something so far beyond their comprehension that lesser persons (such as me?) would’ve run from the table in terror. But faith, by definition, is believing in the unknown with no tangible reason to do so. The ultimate faith is the ultimate blindness.

Did I say “atonal” back there? Isn’t religious music supposed to have ethereal sopranos, triumphant fanfares and driving rhythms such as those in the more modern choral works of John Rutter? Where’s the evangelistic certainty of the religious right? Musically, Rutter has never felt any more authentic to me than the scores to aforementioned Biblical epics of the 1950s and ‘60s. Is it possible that Bach chorales were the last word in authentic religious certainty?

In my world, faith and doubt are twin states of being. One can’t truly exist without the other. Their progeny are courage and apprehension. What I like most about the 21st-century faith-based music I’ve encountered is how it embraces the idea that the divine is beyond comprehension, that’s it’s not a version of our world. And, if nothing else, the divine is a lot less cluttered. The artistic sea change that happened in Arvo Part’s music in the ’70s – paring down his music to essentials – also came with a devotion to sacred texts.

Returning to Princeton: Blessed Art Thou Among Women adds the significant wrinkle of atonality. Spears chose Marian texts by the troubadour Guiraut Riquier in what was more a meditation on the Blessed Virgin Mary than an opera per se, and the musical style that came along with those texts was spare harmonies with tentative relationships to tonal centers. The closest comparison is Gavin Bryars, though Spears offers more shapely vocal lines and an unambiguous sense of artistic purpose. The spareness is important. Divinity, it seems, is devoid of clutter.

O’Regan’s piece, The Wanton Sublime, based on Rabinowitz’s book of the same name, was more frankly operatic, with Mary being so taken aback by the Immaculate Conception that one might call it the “pro-choice” version of the story. Mary tries to drive away the angels and warns them that she doesn’t really have to participate in what they’re annunciating – until she finally dons the iconic blue garb. Some passages, particularly at the beginning, were so spare and atonal that they could’ve been Schoenberg’s. Dramatically, it couldn’t have been more effective in terms of telegraphing to the audience that all concerned parties were on new, barely comprehensible ground.

Once thought to be of use mostly for expressing anxiety, depravity and insanity (as codified in Wozzeck and Lulu), atonality is now associated with things unfathomable, and thus can’t help but be associated with realms of high spirituality. Simplicity equals clarity. And the divine, it would seem, speaks in no uncertain terms. Spareness, together with atonality, could hardly work better.

And how does Vivaldi fit in with this? One of the composer’s more considered pieces, the Stabat Mater also has a lot of Vivaldi’s trademark lengthy melismas. That might seem to go against the grain of J.S.Bach’s practice of always telegraphing high divinity with a sort of orchestral halo – namely around the voice of Christ – as well as keeping the vocal lines relatively unadorned. This is not to say that Jesus and Mary should have coloratura technique. But their inspired bystanders do. Vivaldi’s long-breathed runs became something of an ecstatic, otherworldly elaboration, sort of an artistic way of reaching for God. The determination, yearning and simple level of accomplishment required to meet these steep vocal requirements, and make them musically convincing, certainly telegraph the idea that many are called but few are chosen.

.

> Where’s the evangelistic certainty of the religious right? <

Banging a tambourine in a chapel in Richmond, VA, I would imagine? 🙁

“Atonal music-music with no home key-never developed into a universal artform precisely because there is no sense of direction.”-THE ART OF POSSIBILITY, Zander and Zander, p.172 (Penguin Books,2000).

Thanks for this article.

I think you’d be interested in the work of the Swedish composer Sven-David Sandström, especially his High Mass. I think he’s one of the most prolific and important composers working with religious themes today.

Thanks for the piece, David – the pieces you are writing about sound fascinating. Is there a link to the Birtwhistle?

A technical point of Catholic theology – the term “Immaculate Conception” refers not to the conception of Jesus, but to that of the Virgin Mary – that she was born without blemish of Original Sin, and hence a worthy bearer of the Son of God.

The point is obviously not crucial to what you are writing about, but the “misconception” (sorry!) is so widespread I thought I should point it out.

Thanks! I was born and raised Catholic but some of the fine points are a bit hazy, perhaps due to Rilke’s verse on the subject. I’m not sure if the links to The Last Supper still exist. I stumbled upon it some months ago before the big crackdown on File Serve, etc., that did away with many links. I’ll get back to you.