In the haphazard rogue’s gallery of Rossini’s 39 operas, Guillaume Tell stands apart: As much as it grew out of his past, it was far more than one could have hoped for.

Rossini had effortlessly become famous and stayed that way by putting forth rather less effort. Beethoven, of all people, all but encouraged Rossini to under-achieve: “Never try to write anything else but opera buffa; any other style would do violence to your nature.” But Beethoven never knew Guillaume Tell.

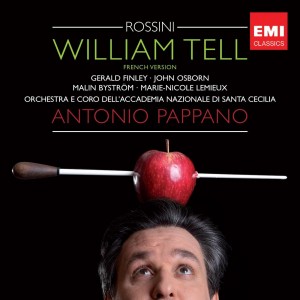

Rossini without Tell is like Offenbach without Tales of Hoffmann. Yet public perception of Rossini has been largely without Tell – though that’s likely to change, perhaps drastically, now that the opera is suddenly in the air. Something close to complete concert performances unfolded at the Caramoor Festival in Katonah, N.Y. and at the London Proms at Royal Albert Hall within days of each other in mid-July. A fine, high-profile EMI recording conducted by Antonio Pappano (with a cast similar to the Proms but better) is out in Europe and soon will be in the U.S.

All three encounters (I caught the Proms by radio) reveal one of the great works of its time, one that breathes different air than the composer’s previous works. I had the mixed fortune to discover Tell 30 years ago, before serious encounters with other, less-serious Rossini operas. And it’s been downhill since. In other operas, Rossini often hovers around the heart of dramatic matters but only occasionally lands, so much that I had begun to wonder in recent years if I’d been wrong about Tell. My first live encounter with the opera at Caramoor – on its second performance July 15, not the one that most critics reviewed – was downright magical thanks to conductor Will Crutchfield’s masterful pacing and shrewd vocal casting. Pappano’s just-as-wonderful recording is probably the opera’s best yet.

Though Rossini often re-purposed his operas, Tell is the only score that feels as though all the music could only have been written for that specific piece. In his newly adopted home of Paris, he had studiously altered his composition style to accommodate the more open-ended rhythms of the French language. Recitative, arias and choruses are better integrated, much in the spirit of another transplanted Italian, Jean-Baptiste Lully, some 150 years before. Though Lully developed suffocating musical formulas, Rossini seems liberated from them in the distinctive synthesis he forged. Vocal lines don’t stray far from the usual Rossinian sequences, but they don’t adhere to them either. Similar to Haydn symphonies, Rossini’s sense of invention is constant, with set pieces that never go back to where they started. His orchestration was never richer. The ending is said to be one of the few slow, reflective conclusions in opera before Tristan und Isolde. Innovative or not, that final chorus is emotionally deeper than anything in his later Stabat Mater. Considering that many composers can only evolve so far, one is torn between gratitude for Rossini’s accomplishment and annoyance that he didn’t keep going.

But art isn’t easy. And Rossini had been at it long enough that he might’ve begun his near-40-year retirement before Tell, suggests scholar Philip Gossett. Thus, Tell joins a select company of works that were both creative breakthroughs and dead ends. Unlike the Mozart Requiem (in which the composer opened new doors while dying), some of the most beloved unfinished works were abandoned. Schubert’s “Unfinished” Symphony No. 8 is the most obvious candidate. Bruckner laid down his pen after many attempts to finish the final movement of his Symphony No. 9, according to Wagnerian scholar Robert Bailey – though from what I’ve heard of the sketches completed with minimal intervention, the composer was in shouting distance of victory. Mahler stopped work on the Symphony No. 10 not due to illness but a psychic crisis precipitated by his wife’s infidelity. And Rossini? Already increasingly distant from the opera stage, he was further intimidated by Meyerbeer’s success in Paris two years after Tell, and concluded he couldn’t change to suit the times. But he already had.

So often in the creative process, the moment of total impasse often means that a breakthrough is near. Not realizing that, artists are likely to see only defeat and a sense of shame for wasting time on a piece that couldn’t be completed. It all looks impossible – one reason, perhaps, why George Rochberg often said composing requires and iron stomach. Even outwardly-cheerful Rossini? One of the most successful opera composer of all time? How odd to think that he felt compelled to follow a world that he had a major hand in creating – and may have thought himself incapable of doing so. That’s clinical depression for you – another factor in his retirement. A bigger question might be why the public didn’t hear that achievement. Well, it did. All too much.

The overture passed into cliché-dom due to the kind of extra-musical associations that aren’t likely to spark interest in the rest of the opera: “The Lone Ranger” was a lousy TV show even by 1950s standards. Divorced from that, the overture’s variety and richness stand far beyond most any other in the composer’s output – and you need a scholar like Gossett to point that out. Even so, the opera is discussed like some curio that somehow isn’t worth its four-hour-plus length.

On a concrete level, Tell lacks a definitive form as much as Verdi’s Don Carlo, existing in different languages and with lots of optional music. It’s a phone-plan opera, each plan having a bewildering array of pluses and minuses. Another problem is vocal casting: The French version is written for long-extinct tenors with a high (and probably airy) upward extension – a range that sounds awful even when the best modern tenors bully their way into the stratosphere in chest voice. Also, the title role’s vocal writing lies not in a weak part of the voice but a less-interesting region that doesn’t show off any baritone to its best advantage. Both Daniel Mobbs at Caramoor and Gerald Finley on the EMI recording over-ride this with communicative vitality since Tell, after all, is about important things.

Unlike Barber of Seville, which I heard in something close to an uncut performance the same weekend in a production by Opera New Jersey, stage time isn’t taken up with thematic reprises or taking one more loop around the park for amusement purposes. Everything in Tell earnestly accounts for itself, so much that the usual Rossini vocal ornamentation seems strangely out of place here. At Caramoor, ornaments were only conspicuous in the great soprano aria, “Sombre forêt” – highlighted the music’s lyrical glories rather than cluttering – in Crutchfield’s un-indulgent tempo that kept the piece moving. The aria’s character, Mathilde, wasn’t cast by Pappano or Crutchfield with the vocal lushness of Montserrat Caballe (whose recording was a standard bearer at one time), but with dramatically alert sopranos, respectively Malin Byström and Julianna Di Giacomo. The leading tenor role of Arnold was sung with greater success than the chesty tenors, but John Osborn (Pappano) and Michael Spyres (Crutchfield) have yet to hit the ideal.

Great Handel operas distinguish themselves from the good ones by virtue of some great soliloquy by a significant character. Similarly, Rossini’s beautiful Abraham-and-Isaac moment – when freedom-fighter Tell is being forced to shoot an apple off the top of his son’s head and thus counsels the boy to stand very still — puts the opera in its own pantheon. Both Mobbs in Caramoor and especially Finley on EMI approached it with the specificity of song recitalists. One curious feature is that Mobbs, an adept actor, has developed his own version of emblematic gestures, the sort that disappeared along with Lotte Lehmann in early ‘50s. But these gestures are completely organic to him and create an emotional broad stroke that draws you into the music.

Any Guillaume Tell advocate would logically push for full productions to complete the opera’s rehabilitation. Not me. Anything high concept would create distance from the piece. Any specific evocation of 14th-century Swiss life can only devolve into grand opera cliche. At the moment, the opera seems best semi-staged. Maybe we’d better know what to do with it had there been a more consistent performance history or if the opera had descendants. But Tell is only the first installment of what might’ve been a great body of work and a needed foil to Meyerbeer, whose grand, once-popular works are now called extinct volcanoes. Rossini is said to have seriously considered writing his own version of Faust. And to think he could’ve saved us from the middle-class, derivative Gounod version. Rossini’s shade has much to answer for.

Thanks for writing about this magnificent opera. It sounds like you didn’t get to see the incredible performance of the complete version in the Gossett edition, complete with the ballets, that was presented at the Rossini Festival in Pesaro, Italy in 1995. It was music directed by Gianluigi Gelmetti, stage directed by Pier Luigi Pizzi and featured the National Ballet of Cuba, with soloists Alessandra Ferri and Jose Manuel Carreno, the Stuttgart Radio Orchestra, the Radio Chorus of Krakow and and Chamber Chorus of Prague, and singers, Michele Pertusi, Gregory Kunde, Daniela Dessi, Elizabeth Norberg-Schulz, Riccardo Ferrari, Paul Austin Kelly, and Jeffrey Francis. I attended the premiere performance, which was six hours long, and utterly astonishing. Six of the shortest hours of my life. The performances were nuanced, superb from all quarters, the singers and dancers all at the height of their powers. The following day it was the front page story in every Italian newspaper–the revival of the complete version of William Tell. But considering that there were over 300 people involved in the performance, and a monumental set and production, to the best of my knowledge, after that run, that production was not done again. I will live in my memory forever. Let’s hope for many more performances of this great opera.

Sorry, it was the Elizabeth Bartlet edition, not Gossett.

Wow…I want your memory! Any chance of live tapes floating around? It’s not the same, I know.

You know, people say that critics are influenced by what they ate that day, what kind of afternoon they had, etc. etc. Well, I had a terrible drive up there (traffic, heat, road construction) and the Caramoor concessions were pretty much sold out when I arrived minutes before curtain. None of that mattered in the least.

dps

A number of years ago Tell was staged by the San Francisco Opera. I recall my reaction at the time was ‘why isn’t this done more often.’ But I still feel part of the problem is that the many dances and chorus numbers stop the forward flow to the opera to often. Of course the other problem is that like American operas, French operas are pretty much looked down on b.y opera managers

Maybe the part of the problem is finding word-based singers who can handle the notes and sing credible French. There really aren’t that many around.

DPS

Just discovered your blog; sorry for the late posting here. I caught the Proms performance that you mentioned back in July, literally so, as I was at the RAH in the Gallery. The orchestra impressed me the most of all, with a really refined sound and excellent ensemble, the more impressive that Italy isn’t really known for its symphony orchestras (as opposed to opera orchestras). Likewise, John Osborn gets points for simply getting through this monstrously difficult tenor role. Even if it was judiciously trimmed, 4+ hours of opera for £5 is a deal, even if standing up and leaning against a rail.

I suppose that if the Metropolitan Opera ever gets around to staging “William Tell”, they’ll try to recruit Juan Diego Florez. Of course, the Met has other problems at the moment.

Tell’s future at the Met might be brighter than we think. Wasn’t it Fabio Luisi who conducted that live recording on Orfeo? And the Met has him.

dps

Good heavens! How can anyone say that the Lone Ranger was a lousy TV show. Obviously, you’ve never seen it as a youngster. It was fabulous and many a child’s introduction to classical music via the famous overture. Quelle Scandale!