On the last day of 2013, I hurried my husband and children through the bitter, late afternoon cold and up the sweeping outdoor staircase of New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. We were going to see “Ink Art: Past as Present in Contemporary China,” the august American museum’s first major exhibition of contemporary Chinese art (which runs until April 6).

Snow-laden clouds brooded overhead and the tantalizing aroma of roasting chestnuts and steaming hotdogs wafted from silver food trucks clustered at the base of the stairs. Stalwart, I resisted all pleas and protests – no Times Square, FAO Schwarz, hot pretzels, or chilled champagne! – determined that we should have as much time as possible to view the 70 works by 35 artists.

But then, out of the blue, came a familiar tune that caused us all to stop in our tracks: an elderly, African-American busker with a saxophone and a battered, coin-filled case had spotted a group of Chinese tourists and was cheerfully serenading them with “March of the Volunteers.” We waited until the end of the song – the perfect prelude to the exhibition – and then marched on into the museum, marveling at these dual harbingers of China’s global cultural arrival.

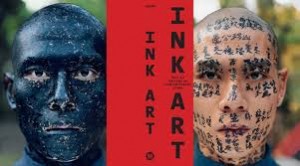

“Ink Art” is an intriguing, meaty show that includes works by a roster of China’s best known contemporary artists: Xu Bing, Zhang Huan, Zhan Wang, Song Dong, Ai Weiwei, Gu Wenda, Liu Dan, Fang Lijun, Cai Guoqiang, Xing Danwen – and the list goes on. The exhibition is divided into four sections – “The Written Word,” “New Landscapes,” “Abstraction,” and “Beyond the Brush.” It is accompanied by an excellent catalogue (which can be ordered online) that includes introductions to the artists and their works by curator Maxwell K. Hearn and an essay on the history of contemporary Chinese ink painting by the renowned University of Chicago scholar Wu Hung.

In “The Written Word,” viewers are given a fascinating overview of the creative, often subversive attitude with which contemporary artists have approached the Chinese written language. Hearn suggests that this experimentalism has roots in the Mao era when written Chinese was radically simplified (with the aim of promoting literacy) and ubiquitous, with political “big character posters” plastered everywhere – even hung around the necks of those persecuted by Red Guards. The section includes several works from Gu Wenda’s “Mythos of Lost Dynasties Series” including the hauntingly beautiful “Synthesized Words,” an ink-splashed landscape in which a made-up character floats in the sky.

Fake characters take center stage in Xu Bing’s “Book from the Sky,” an iconic work that is given its own gallery. Like Gu, Xu grew up in the era when language was radically politicized and characters radically simplified – to the point that Premier Zhou Enlai himself complained “there exists a certain lack of consistency in the use of simplified characters. There are some who freely coin simplified characters which nobody except themselves can make out.” While the 1200 characters in Xu’s “Book” are completely consistent, carved in traditional wooden movable type and printed in nine columns on hand-stitched paper, they utterly nonsensical – not even the artist himself can make them out. Xu’s “Square Word Calligraphy,” on the other hand – on display in “The Song of Wandering Angus” – appears at first glance to be unintelligible characters but in fact is English words made to look like Chinese writing. The process of trying to read them is simultaneously scintillating and headache inducing.

“New Landscapes” includes a wide variety of works on paper and video that reflect China, in Hearn’s words, as “arguably the most human landscape on earth.” These include Huang Yan’s “Chinese Landscape Tattoo No. 2 and No. 4,” striking photos of the artist’s torso painted with a traditional landscape; Liu Dan’s surreal hand-scrolls; and Yang Jiechang’s “Crying Landscape,” a set of five color triptychs that includes one of a plane about to crash into the Pentagon.

The environmental impact of China’s unprecedentedly fast economic development is mirrored by a number of artists. Qiu Shihua’s three “Untitled” landscapes are shades of white and grey, intimations of fog and mist, with no discernible objects; though they are described as meditative and calm, they also call to mind the view from a Beijing high-rise on a particularly polluted day. Shi Guorui’s “Shanghai, China October 15-16, 2004” is an eerie, black-and-white photo of Shanghai taken through a camera obscura. The exposure time required by this process is so long that all traces of movement vanish – there are no clouds in the sky, no tugboats on the Huangpu, no vehicles on the Bund – and the resulting image is foreboding, almost post-apocalyptic. Similarly, Yang Yongliang’s “View of Tide” initially looks like a faithful copy of a Song Dynasty landscape – until you get up close and realize the mountains are made of digitally superimposed high-rises and the trees of power-line towers and construction cranes. There are no paths and no people – we have consumed and built ourselves out of existence.

While the works in “Abstract” are all ink and paper – including Li Huasheng’s compelling freehand grids, drawn in a painstakingly repetitive process that the artist compares to chanting sutras – “Beyond the Brush” serves as a sort of catch-all for the works of interesting and important artists whose work may not use much ink but, to quote Hearns, exhibit “an ink art aesthetic.” These include Cai Guoqiang’s “Project to Extend the Great Wall by 10,000 Meters: Project for Extraterrestials No.10;” Zhan Wang’s gorgeous “Artificial Rock No. 10;” and a number of pieces by Ai Weiwei, including his well-known “Han Dynasty Urn with Coca-Cola Logo.” (Indeed, there are so many non-ink related pieces by Ai Weiwei in “Ink Art” that it seems fair to wonder if “Beyond the Brush” was added largely to accommodate his work.)

All the works in “Ink Art” are displayed in the Met’s Chinese galleries, spread among its collection of ancient porcelain, scrolls, and sculptures. Met director Thomas P. Campbell told journalists that this was done to contextualize the contemporary artworks “in a way that no other museum can” by enabling visitors to see the traditional Chinese approach to ink, and other art forms, alongside the contemporary. Further contextualization – for me anyway – comes from the fact that contemporary art from China has finally been given a big exhibition at the Met, accompanied by thoughtful reviews and a catalogue, and heralded by street musicians. The show encompasses the diverse, dynamic work of so many creative, boundary-crossing, and, thankfully, still living and creating Chinese artists that the biggest curatorial challenge seems to have been culling and categorizing.

Since I find this so exciting, I figured so would the Chinese media and government, which in recent years have put tremendous effort and resources into trying to make Chinese culture “go global.” Indeed, on New Year’s Day, Xinhua wrote “President Xi Jinping has vowed to promote China’s cultural soft power by disseminating modern Chinese values and showing the charm of Chinese culture to the world… China should be portrayed as a civilized country featuring rich history, ethnic unity and cultural diversity, and as an oriental power with good government, developed economy, cultural prosperity, national unity and beautiful mountains and rivers, Xi said.” But “Ink Art” – which consists of works borrowed from private donors, many of them foreign – has thus far received only perfunctory coverage in China, with far more ink given to “Exhibition of Contemporary Chinese Paintings – Ink Wash Paintings of the Chinese Dream,” a five-day show staged at a private New York club by the Beijing International Cultural and Creative Industry Company and the China Artists Association.

This leads me to the sad conclusion that the most fundamental context for the export of Chinese culture remains politics. On the official Chinese side, this means continued insistence on art as propaganda and on the government’s right to determine what constitutes culture. On the American institutional and consumer side, this means forever seeking a dissident viewpoint in art and culture from China. Stuck in the middle are Chinese artists who just want to realize their own visions and dreams in their art– and whose persistence and success in doing just that is beautifully documented in “Ink Art.”

(This article was first published in Caixin.)

Leave a Reply