Upon learning that the novelist Mo Yan had been awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2012, Chinese leader Li Changchun penned a jubilant letter that said, according to Xinhua, “Mo’s victory reflects the prosperity and progress of Chinese literature, as well as the increasing national strength and influence of China.”

Upon learning that the novelist Mo Yan had been awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2012, Chinese leader Li Changchun penned a jubilant letter that said, according to Xinhua, “Mo’s victory reflects the prosperity and progress of Chinese literature, as well as the increasing national strength and influence of China.”

Chinese literature is certainly prospering and there are many who would agree with Li’s statement that the prize reflects China’s power and influence; indeed, it is often argued that the Nobel Prize is awarded for political purposes as much as literary merit. It is for this reason that I think a clearer reflection of the country’s growing influence can be found not in its own literature, or the prizes awarded to it, but in its growing role in the literature of other nations.

As an avid consumer of contemporary English-language fiction and of translated European fiction, I have noticed that China is increasingly present in novels from the West that center on topics completely unrelated to it. In some stories, China plays a fleeting, familiar role as an exotic other, a destination to which the protagonist aspires or a land in which his dreams may be realized.

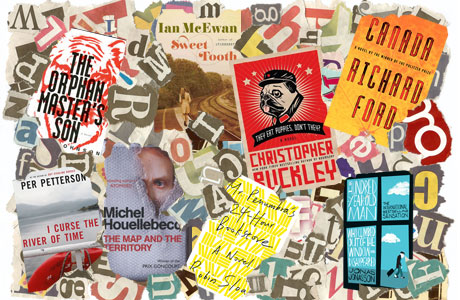

In The Woman Upstairs, by the American author Claire Messud, the protagonist Nora Eldridge is an unhappily unmarried elementary school teacher in Boston who dreams of visiting “Ayers Rock, the Great Wall of China, Angkor Wat …” (Another character in the novel has an adopted Chinese daughter.) So, too, in British novelist Deborah Levy’s Swimming Home in which the despondent Kitty Finch is obsessed with a poet who says of her, “She must travel to the Great Wall in China…These were all things to look forward to.” American writer Adam Johnson raises China’s status as a land of aspiration to a higher plane in The Orphan Master’s Son, set in North Korea. “‘We looked at the lights glowing in the guard buildings,'” says one North Korean character. “We looked toward China.'”

Other novels reflect the zeitgeist that has come to prevail in many Western countries (perhaps especially the U.S. and Britain) in which China is viewed as a threat. In Mr. Penumbra’s 24-Hour Bookstore, by American writer Robin Sloan, the Silicon Valley protagonist Clay Jannon matter-of-factly states:

The buzz about Google these days is that it’s like America itself: still the biggest game in town, but inevitably and irrevocably on the decline. Both are superpowers with unmatched resources, but both are faced with fast-growing rivals, and both will eventually be eclipsed. For America, that rival is China. For Google, it’s Facebook.

In American author Richard Ford’s Canada, narrator Dell Parsons has not seen his sister for decades and when he finally does, she is dying. Nonetheless, in their conversation: “She said she’d become interested in China and its growing dominance…” The reference to China in British writer Ian McEwan’s Sweet Tooth is passing, but blunt. Protagonist Serena Frome is in a restaurant “where men of a certain age with jowly ruined faces were perched on stools at the bar, pronouncing loudly on international affairs. As we came in one said loudly, ‘China? Fuck off. China!'”

In some novels, China plays roles both desirous and dangerous. The best example I’ve seen is May We Be Forgiven, by American A.M. Homes (which just won the Women’s Prize for Fiction). The story portrays the crumbling life and career of historian Harold Silver who studies (and identifies with) Richard Nixon. Silver’s soon-to-be-ex-wife is Chinese-American and she is in China on business when he beds his brother’s wife, an act that ends with murder and his brother’s imprisonment. In the process of rebuilding, Silver makes friends with a Chinese immigrant named Ching Lan, who asks “What do you like so much about China?” He answers:

“This may sound odd, but I like how big it is – China has everything from Mount Everest to the South China Sea, and how many millions of people live there, how industrious they are, the depth of the history, how ancient, beautiful, mysterious and other it is.”

Silver then relates:

“What I don’t tell Ching Lan is that I am also secretly terrified of China: I imagine a dark side that doesn’t value human life as deeply as I do. I worry that if I went there something would happen to me, I would get sick, I would rupture my appendix, I would end up doubled over in a Chinese hospital unable to care for myself. I imagine dying of either the gangrenous appendix or perhaps an infection following surgery performed under less-than-sterile conditions. I don’t tell Ching Lan that I have nightmares that involve Chinese people wearing bloody lab coats telling me in broken English that my turn is next. I also don’t tell Ching Lan the one big idea that I’ve not yet articulated. I don’t tell Ching Lan that I can’t help but sometimes wonder if the current world economic crisis could be directly linked to Nixon’s opening relations with China.”

A third category of novels – the one I prefer – treats China as a normal part of global society, neither exotic nor threatening. (Interestingly, the best examples of this are European.)

The Map and the Territory by French writer Michel Houellebecq is set in a not-too-distant future in which France is “a mainly agricultural and tourist country” that offers hotel rooms, perfumes, and the art of living to foreign tourists, notably Chinese. In describing a scenic village, Houellebecq writes:

“Most of the houses that their former owners from northern Europe no longer had the means to maintain had, in fact, been bought up. The Chinese certainly formed a rather closed community, but, truth be told, mo more, and even rather less so, than the English had done in the past – and at least they didn’t impose the use of their own language.”

The novel features an artist, Jed Martin, whose painting is inspired by old issues “of Peking-Information and China in Construction” and is reminiscent of “the group of agronomists and middle-poor peasants accompanying President Mao Zedong in a watercolor reproduced in issue 122 of China in Construction, entitled Forward to Irrigated Rice Growing in the Province of Hunan!”

The 100-Year-Old Man Who Climbed Out the Window and Disappeared is a joyous romp through history by Swedish writer Jonas Jonasson. The protagonist, Allan Karlsson, is an explosives expert whose remarkable life has brought him in close contact with world leaders like Franco, Truman, Stalin – and Mao. Indeed, Mao Zedong is a character in the novel, as is his wife Jiang Qing – who Karlsson rescues from imprisonment by drunken KMT soldiers. (It’s fiction!) Later, when he himself is in a tight spot with Kim Il-sung, Chairman Mao comes to the rescue, even offering Chinese citizenship.

“But Allan answered that just now – and Mr. Mao would have to excuse him for this – he had had all he could take of communism, and he longed to be able to relax somewhere where he could drink a glass of something strong without an accompanying political lecture.”

The understanding Mao gives Karlsson a pile of American dollars and suggests he go to Bali.

Mao also figures in Norwegian writer Per Petterson’s I Curse the River of Time, the title of which was inspired by a translation of Mao’s 1959 poem Shaoshan Revisted. The narrator, Arvid Jansen, was once a passionate Marxist who had a portrait of Mao hanging above his bed (alongside Bob Dylan and Joni Mitchell). His brother teased that he talked to Mao – which he denied – but he did admit to gazing at the portrait and imagining “the human Mao, someone I was drawn to…” But then, in 1989, the narrator’s admiration for the Chinese Communist Party dims and he finds himself protesting outside the Chinese Embassy in Oslo, wondering, “What do we do now?”

The question remains unanswered in the novel, but asked more broadly of contemporary literature, I think I can answer: We read more books in which China – and our perceptions of it – plays an ever more prominent role.

This article was published first in Caixin http://english.caixin.com/2013-08-02/100564875.html

Leave a Reply