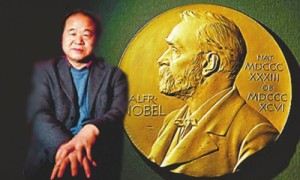

Nobel Prize for Literature Goes to Chinese Writer Mo Yan

A Nobel Prize has at long last been awarded to a Chinese who lives inside China, and outside prison.

Mo Yan, the 57-year old author of numerous novels and short stories, was awarded the prize this morning. He is the second Chinese to receive the Nobel Prize for Literature. However, the first – Gao Xingjian – lives in Paris and is a French citizen who says he has no intention of ever returning to China. Liu Xiaobo, the winner of the 2010 Peace Prize, is a literary critic who is imprisoned in China for his political activities. Chinese press coverage is thus calling the prize, China’s “first.”

The awarding of the prize to Mo Yan will certainly be seen in China as another step in the nation’s cultural rise. It will also finally help lay to rest the Nobel Literature Prize obsession that has possessed China’s cultural and literary establishment for decades now – a mania that Liu Xiaobo, when he was a free man, called “childish.” (The Nobel Literary Prize obsession has been documented by Julia Lovell in her 2006 book “The Politics of Cultural Capital: China’s Quest for a Nobel Prize in Literature.”)

Many of Mo Yan’s works have already been translated into English, including Red Sorghum (which the director Zhang Yimou made into a film in 1987), The Republic of Wine, and Big Breasts & Wide Hips. Mo’s translator is the prolific Howard Goldblatt, who compares the author’s work to that of Charles Dickens. Mo himself admits to being influenced by William Faulkner and Gabriel Garcia Marquez, a link the Nobel Prize committee seems to have picked up on in commending Mo “who with hallucinatory realism merges folk tales, history and the contemporary.”

Mo’s writing is often epic, visceral, and bawdy. Many of his tales are set in his hometown of Gaomi, in Shandong Province, where the author was home eating dinner when he received news of the prize. Among these is Big Breasts & Wide Hips which tells the story of a monstrous boy named Jintong who grows up surrounded by women – including an all-powerful Mother, whose milk he insists on drinking for years beyond infancy – and buffeted by the many cataclysmic events that struck the Chinese people in the 20th century.

In the horrifically gripping opening scene of Big Breasts, Shangguan Lu (the mother) is in labor, alone; her husband and mother-in-law are too busy delivering a donkey foal to be at her side. This is just as well, since the birth of her last child – a seventh daughter – so enraged her husband that he threw a hammer at her head, splattering part of her skull onto the wall. Taking a break from the donkey delivery, the mother-in-law stops in to see how Shangguan Lu’s labor is progressing:

“I thought you’d have had it by now.” [She] reached out to touch her belly. Those hands – large knuckles, hard nails, rough skin, covered with blood – made her cringe; but she lacked the strength to move away from them as they settled unceremoniously onto her swollen belly, making her heart skip a beat and sending an icy current racing through her guts. Screams emerged unchecked, from terror, not pain. The hands probed and pressed and, finally, thumped, like testing a melon for ripeness. At last, they fell away and hung in the sun’s rays, heavy, despondent, as if she’d come away with an unripe melon…. She watched one of those hands descend weakly and, disgustingly, thump her belly again, producing soft hollow thuds, like a wet goatskin drum. ‘All you young women are spoiled. When your husband came into this world, I was sewing shoe soles the whole time…’”

The mother-in-law departs, saying “Our donkey’s about to foal. It’s her first, so I cannot stay with you.” Shangguan Lu then prays for the donkey.

Mo has been criticized within China for being too close to the establishment; he is a recipient of the 2011 Mao Dun Literary Award and some interpret his writing as praising authoritarianism. China’s Weibo is already alive with criticism of the choice – as would be the case no matter who won. It seems fairer to say that Mo walks a fine line, does his best to stay true to himself as a writer, and, perhaps wisely, avoids the punditry circuit. Indeed, his self-chosen name means “doesn’t speak.”

In a 2009 speech at the Frankfurt Book Fair, quoted by Raymond Zhou in China Daily, Mo briefly explained his philosophy:

“A writer should express criticism and indignation at the dark side of society and the ugliness of human nature, but we should not use one uniform expression. Some may want to shout on the street, but we should tolerate those who hide in their rooms and use literature to voice their opinions.”

He also added a well-known anecdote about Beethoven and Goethe, walking together in the Czech spa town of Teplitz, when they saw the Empress passing by; Beethoven continued onward, but Goethe removed his hat and bowed.

“When I was young, “ Mo Yan said, “I thought what Beethoven did was great. But, with age, I realized it could be easier to do what Beethoven did, and it might take more courage to do what Goethe did.”

Interview with Mo Yan:

http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/china/2012-10/11/c_131900918.htm

Leave a Reply