The Philadelphia Orchestra has arrived in Beijing and taken up its unusual ten day China “residency,” which will consist of concerts in Beijing, Tianjin, Shanghai and Guangzhou; master classes; small break-out performances at important cultural sites; and numerous musical exchanges. The Orchestra will travel to China for a longer, three-week residency in 2013 and reportedly hopes to sign a deal extending this arrangement for at least five years.

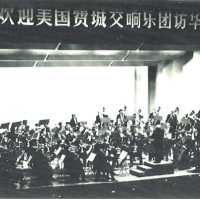

This rather remarkable undertaking – begun as the Philadelphia Orchestra strives to emerge from Chapter 11 bankruptcy – brings full circle a relationship started by Maestro Eugene Ormandy when he took the orchestra to Beijing and Shanghai back in 1973. China was then in the midst of the Cultural Revolution and –at Premier Zhou Enlai’s initiative – had just begun to allow the performance of Western classical music on a highly restricted basis for the first time since 1963.

Beijing’s beleaguered symphony, the Central Philharmonic, had spent eight years studying Mao Zedong’s “Little Red Book” and performing one revolutionary symphony (“Shajiabang”) so often that its conductor, Li Delun, told us he “could conduct it upside down.”

But, the Philadelphia Orchestra visit gave the Central Philharmonic license to rehearse two banned works: Beethoven’s “Fifth Symphony” and Wu Zuqiang’s “Moon Reflected on Erquan Spring.” Ormandy attended a Central Philharmonic rehearsal and conducted the delighted orchestra in a run-through of the Beethoven. He expressed admiration for “Erquan Spring,” and even asked for a copy of the score so he could perform the work in Philadelphia.

Four concerts were scheduled for the Orchestra in Beijing and two in Shanghai. The first two Beijing events went smoothly, but the third was complicated when Mao’s wife, Jiang Qing, suddenly announced that she would attend. On hearing the news, Ormandy changed the program to include the Yellow River Piano Concerto, adapted from Xian Xinghai’s “Yellow River Cantata.” Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony was also on the program – until Jiang Qing sent word through interlocutors that she would prefer the Sixth. This caused some consternation, but Ormandy obliged and the orchestra borrowed the parts for the Sixth from the Central Philharmonic.

All went well at the concert – according to Maestro Li – until the orchestra played Respighi’s “Pines of Rome.” (The Respighi upset Jiang Qing because she didn’t think it sounded like pines.) Then, when she went backstage to meet Ormandy – and thank him for organizing a concert to benefit medical workers with the Communist Eighth Route Army back in 1940 – he asked her why Russian music had been banned, upsetting her even more. Later, she became further incensed when she read translations of The New York Times’ scathing reviews of “Erquan Spring” and “Yellow River Concerto.”

As far as the Philadelphia Orchestra was concerned, the concert tour was a resounding success – but from the moment the orchestra departed, Jiang Qing worked to put an end to the classical music diplomacy supported by Premier Zhou Enlai. She found her first opportunity with the planned visit of a Turkish pianist who had been invited to concertize in Beijing. All music to be performed required approval from the highest echelons of government; a list of the works to be played, with descriptions (in this case written by Maestro Li), was circulated among them and they could comment if they chose. When Jiang Qing and her radical Gang of Four colleagues read Maestro Li’s explanation that the pianist would play “standards for soloists… with no deep social content, no clear story, and no descriptive title” they went ballistic.

In the view of the radicals, all music had both social and class content – even if a composition was absolute music with no descriptive title or clear story line, it nonetheless reflected the composer’s thinking and his class stance. Jiang Qing also noted her opinion that the music of Schumann and Brahms resembled sobbing and that works by some other bourgeois composers were difficult to understand and even sounded like someone going crazy! In all this back and forth, the date of the planned recital came and went, with no approval. When Premier Zhou tried to schedule a new date, Jiang upped the ante, declaring that China should not receive any arts groups from capitalist countries. She then went to the press and started a small political campaign against “music without titles,” or absolute music.

This campaign was in full swing when Maestro Li received a letter from Maestro Ormandy in the spring of 1974 informing him that the Philadelphia Orchestra would play “Erquan Spring” at concerts in Philadelphia, Washington, and Baltimore and asking for some background information on the piece. Maestro Li had to ask Jiang Qing’s permission to comply – which was denied. He was thus forced to write Ormandy to warn him the piece should not be performed – and that to do so would hurt the “friendship” of the Chinese and American people. Ormandy dropped the piece; no more foreign orchestras or musicians visited China until the end of the Cultural Revolution in the autumn of 1976. Maestro Li wrote Ormandy again in 1977 to say “Erquan Spring” could now be played, but received no reply; in the last years of his life, he still regretted having to send that unfriendly letter to the Philadelphia maestro he admired.

Ormandy and Li would doubtless be delighted to know that the relationship they began in China’s darkest days has now been formalized – and surprised that it takes place with the Philadelphia Orchestra in bankruptcy and China building new concert halls and opera houses like there is no tomorrow. Times have certainly changed.

This is only hearsay, but on the visit in ’73, the then principle bass started the Shostakovich Symphony #5 a face-palming one beat early!