China’s potent mix of socialism and capitalism – frequently synergetic and ceaselessly fascinating – is also the root of countless unresolved problems, most having to do with ownership. Land, of course, is the big one – but there are issues in the arts, too.

One such problem is the legacy of collectively-created art from the socialist era that has considerable economic value in these state-capitalist times. Several years back there was a lawsuit threatened over the New York-based artist Cai Guoqiang’s appropriation of “The Rent Collection Courtyard,” a socialist-realist sculpture containing more than 100 figures engaged in class struggle that was made in 1965 at the Sichuan Academy of Fine Arts. Angry artists who had worked on the original said that Mr. Cai’s award-winning 1999 partial re-creation of the sculpture for the Venice Biennale, which he entitled “Venice’s Rent Collection Courtyard,” was a violation of their creative rights. A drumbeat of nationalist rhetoric ensued, Mr. Cai was pilloried as a “green card artist” and a “banana man” – and then, just a few years later, invited back to China and given a hero’s welcome as he undertook the task of creating the fireworks display for the Opening Ceremony of the 2008 Olympics.

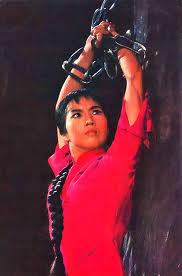

The latest flare-up concerns the ballet “The Red Detachment of Women” which was premiered on October 1, 1964 – China’s first full-length original ballet – and became one of the initial eight “model revolutionary operas” that were performed unendingly during the Cultural Revolution (1966-76). The ballet remains a signature work of the National Ballet of China and a standard part of its repertoire. Its theme is political – “wherever there is oppression, there is resistance and struggle” – and the story revolves around a young servant girl, Wu Qinghua, who, beaten to the point of death, escapes her despotic landlord master and is rescued by Hong Changqing, a young Communist who leads the Red Detachment of Women soldiers. The story is set on the southern island of Hainan and was adapted from a 1961 movie written by Liang Xin; the movie, in turn, was based on a true story.

Chairman Mao’s wife, Jiang Qing, was a champion of “Red Detachment,” which features rifle-toting ballerinas dressed in military uniforms and borrows liberally from the performance techniques of Peking opera, acrobatics, and folk dance. In suggesting that the story be made into a ballet, Jiang was credited for having “successfully stormed the most stubborn fortress of art till then so tightly controlled by the Western bourgeoisie” and “making a significant beginning in the remolding of the world’s theatrical stage with the thought of Mao Zedong.”

“The Red Detachment” features in John Adams’ opera “Nixon in China” – and President Nixon did, in fact, go to see it with Jiang Qing on his 1972 visit to China.

“I had not been particularly looking forward to this ballet,” Nixon wrote later, “but after a few minutes I was impressed by its dazzling technical and theatrical virtuosity. Jiang Qing had been undeniably successful in her attempt to create a consciously propagandistic theater piece that would both entertain and inspire its audience. The result was a hybrid combining elements of opera, operetta, musical comedy, classical ballet, modern dance, and gymnastics.”

At the time of its re-creation as a ballet, “The Red Detachment” was credited to a collective creation group of the Central Ballet of China – individuals did not get creative credits during the Cultural Revolution. However, named or not, it still had individual creators – and Mr. Liang was clearly one of them. When China’s first copyright law came into effect in 1991, the China Daily reports, Mr. Liang contacted the ballet to negotiate a royalty payment; he eventually received RMB 5,000. The lawsuit has come about because Mr. Liang – who is now in his late 80s – and his daughter and son-in-law say that the initial agreement was for a ten-year term; they are asking for RMB 550,000 in compensation for royalties unpaid since then. The National Ballet did not comment publicly, but its lawyer says there was no time limit on the royalty agreement and that the ballet hasn’t made a profit anyway. The case is being heard in a Beijing court.

Legal issues aside, the lawsuit raises a question worth pondering: why is a Cultural Revolution-era ballet about class-struggle still the best-known – and loved – Chinese ballet in the repertoire of the National Ballet of China?

The other best-known ballet, performed primarily by the Shanghai Ballet, is “The White-Haired Girl” – it, too, was a “model revolutionary opera” about an enslaved girl who rises up against her master. Both are worthy creations that have, ironically enough, stood the test of time – but it seems unfortunate that the “era of reform and opening” that began in 1979 has yet to produce (with the possible exception of Zhang Yimou’s “Raise the Red Lantern,” also a tale of oppressed women based on a movie and set in the pre-liberation era) any worthy competitors.

Leave a Reply