China’s Ministry of Culture has announced a month of celebrations to mark the 70th anniversary of Chairman Mao Zedong’s “Talks at the Yan’an Forum on Literature and Art.”

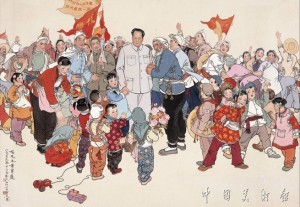

The “Yan’an Talks,” as they are known, are Mao’s seminal statement on the role of art in revolution; their influence on cultural policy remains powerful to this day. Events to mark the anniversary will include a major exhibition of art from the Yan’an era at the National Art Museum of China; a May 23rd performance at the Great Hall of the People of the ballet version of an opera created at Yan’an, “The White-Haired Girl;” a series of “Arts Enter the Universities” events in multiple provinces and many other events.

Mao’s famous address was made to the eclectic group of artists, writers, and musicians who had traveled to the Communist base camp of Yan’an to support the Communist cause. Many of them came, as Mao put it, from the “the garrets of Shanghai” – sometimes via Paris – and were international in their outlook. They composed symphonies, produced plays by Moliere, Chekov and Gogol, founded newspapers and poetry societies, and generally aimed to create a diverse and flourishing cultural life. Although Mao was willing to acknowledge that their intentions were good, he increasingly came to believe that they did not understand their audience or the political role they themselves were intended to perform.

So, in May of 1942, a conference was called to “examine the relationship between work in the literary and artistic fields and revolutionary work in general.” Mao, a night owl, started his address late in the evening; since the assembly hall was still under construction, he stood outside on a flat stretch of land in front of the cave-dwellings in which the Communists lived and worked. As one attendee poetically described it, “Without any sign of fatigue Chairman Mao spoke on. It was already past midnight. The moon overhead made the night as bright as day. Under the moon and the stars, hills nearby and distant were darkly silhouetted. Not far away, the Yenhe River flowed merrily, its surface shot with silver …” [i]

Talking until dawn, Mao emphasized the importance of culture in revolution – a regular army with guns was the main force, but a “cultural army” was also “absolutely indispensable for uniting our own ranks and defeating the enemy.” For this cultural army to succeed, its members had to be absolutely clear that their mission was to create art for the masses of the people, meaning the workers, peasants, and soldiers. Artists were obliged to “fuse their feelings” with those of the workers, peasants and soldiers and reflect the “real lives” of the people in their work. “Raising standards” of artistic quality was important – but popularizing art for the masses took precedence. The Chinese people, so long repressed by the feudal and bourgeois classes, did not need ‘more flowers on the brocade’ but ‘fuel in snowy weather.’” Mao then emphasized what he considered to be the political nature of all art:

“In the world today, all literature and art belong to definite classes and are geared to definite political lines. There is in fact no such thing as art for art’s sake, art that stands above classes or art that is detached from or independent of politics.”

The anniversary of the “Yanan Talks” is marked every year and celebrated every five years because Mao’s words still matter. Art in China is still expected to serve the people. It is still subservient to the Communist Party – and will be for as long as the Party is in charge. Certainly, there are many individual artists in China who create art as a means of self-expression or for whom, to once again quote Mao (speaking critically), “The fundamental point of departure for literature and art is love, love of humanity.” But art that is publicly funded – like most performing arts – or publicly performed, like film, has to at least ostensibly follow Mao’s tenets.

What this means, practically speaking, is that arts and entertainment can’t be too “dark” or superstitious; that’s why the genre of horror film is so limited in China – ghosts and gore are not allowed. It can’t be excessively satirical or mock public figures, the Party, or the government – that’s why there is no equivalent of “Saturday Night Live” in China, hilarious as that would be. It has to be at least nominally accessible to “the masses;” so, the opera companies and symphonies that perform in China’s stunning new opera houses must also go to the countryside or the factories each year to perform for workers and farmers. Art must convey a “realistic” view of history, which means whatever the Party’s current version of that history is – there are no Oliver Stone-like revisionist film interpretations in China. Likewise, depictions of historic figures must emphasize their more heroic qualities – you cannot depict revolutionary heroes arguing with each other or cheating on their wives. Productions made for export must convey a positive sense of modern China; if a film or a stage production is deemed embarrassing and the government has any control over it, it won’t be allowed out. If it does get out – like a small independent film that reaches a foreign film festival – the government may bring pressure to bear on the overseas presenter of the work. Works dealing with ethnic populations – especially from border regions like Tibet, Xinjiang and Mongolia – are extremely sensitive. It is fine to paint a Tibetan with weather-beaten skin and flowing animal skin robes, but to try and depict one as a real person interacting with Han Chinese in a novel or film would invite censorship. Art and entertainment aimed at kids – like cartoons – has to be morally uplifting, or at least not seen as a negative influence. (Thus, no “Simpsons” in China, and hundreds of thousands of minutes of cartoons that nobody watches.) Last year, the Beijing premiere of an opera about the revolutionary hero Sun Yat-sen by the New York-based composer Huang Ruo was cancelled at the last minute, apparently because its presenters decided the music wasn’t heroic and romantic enough to reflect Sun’s greatness. (The libretto also perhaps dwelled too much on Sun’s complex love life.)

Of course, there is ample room for flexibility in these largely un-written and un-official policies; what won’t pass muster in Beijing might very well play in Guangzhou. A director who infuriates Shanghai culture officials might be welcomed in Beijing. Art that is wide open to interpretation – like dance and contemporary visual arts – can be taken at face value, with multiple hidden meanings overlooked. Video game makers know that censors usually only play the game for three or four hours before deciding whether to approve it, so they save the murder and mayhem for the fifth hour. An artist who can’t get permission to blow up a boulder in Beijing can travel to a neighboring province and gain the requisite approvals. And, economic incentives are growing stronger every year, making officials increasingly likely to overlook things that might once have incensed them.

But, Mao’s “Yanan Talks” still resonate loudly. This doesn’t stop creativity, but it does require that creators think about politics, thus perpetuating Mao’s fundamental thesis: there is no such thing as art that is independent from politics.

Leave a Reply