(UPDATE: The Chatelet production of “Nixon in China” can be viewed here: http://liveweb.arte.tv/fr/video/Nixon_In_China__de_John_Adams_au_Theatre_du_Chatelet/)

(UPDATE: The Chatelet production of “Nixon in China” can be viewed here: http://liveweb.arte.tv/fr/video/Nixon_In_China__de_John_Adams_au_Theatre_du_Chatelet/)

On a cold, blustery day in February of 1972, Jindong’s middle school walked three miles through falling snow and icy streets to reach the Forbidden City. Though it was a scheduled field trip, when they arrived at the back entrance of the palace, near Jingshan Park, they found the gates barred tight.

“There’s an important political personage inside,” they were told. “You can’t come in.”

Even today this is not an unheard of occurrence – entire museums still close unexpectedly so “political personages” can have private tours. Back then, in the midst of the Cultural Revolution, the arbitrary nature of power was one of life’s few certainties, so no one bothered to question the closure. Instead, the teachers mustered their 300 disappointed students for the walk back to Dongsishitiao through the fast falling snow.

But then, of a sudden, a guard called them back. They were told to line up and a handful of students from each class were asked to step forward, Jindong among them. Whispers moved up and down the now-jagged line: the “political personage” inside the vermilion gates was none other than Richard Nixon, president of the nation they had all been taught to hate but were now being asked to welcome. To make the scene look “natural,” a few select students would be allowed to tour the palace grounds – Jindong among them. Although he didn’t run into Richard Nixon, Jindong did get to walk through the palace’s snow-covered grounds in blissful solitude – an unforgettable “Nixon in China” moment.

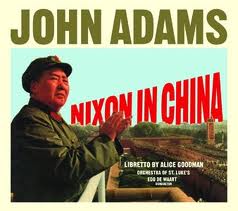

That moment – the visit that shook geo-politics like an earthquake and forever altered its landscape – has inspired many books, memoirs and, perhaps most famously, an opera: John Adams’ “Nixon in China.”

“Nixon in China” premiered in Houston in 1987. The New York Times critic made fun of it – “Mr. Adams has done for the arpeggio what McDonald’s did for the hamburger” – but the opera endured. New York’s Metropolitan Opera mounted it last year, twenty-five years after its premiere, and numerous other opera houses now have it on their schedules: the San Francisco Opera will mount it in June and it is on now in Paris, at Chatelet, until April 18.

The Chatelet production is significant because it marks the first time the opera has been directed by a Chinese director, Chen Shizheng. (Clips here.) Chen grew up in China during the Cultural Revolution; he is from Hunan, Mao’s home province, where the violence of the Chairman’s fading years was considerable – Chen’s own mother was shot and killed by an errant bullet during a supposedly festive revolutionary parade. Chen’s take on the opera is certain to be unique – and, unfortunately, just as certain not to be seen in China. Indeed, despite the hopes of Chatelet – and other opera houses – to come to some sort of co-production or touring arrangement with a Chinese counterpart, “Nixon in China” is unlikely to go to China anytime soon.

There are several reasons for this. For starters, few contemporary operas from outside China are staged in China – even Tan Dun’s “First Emperor” has yet to be mounted and Zhou Long’s Pulitzer Prize winning “Madame White Snake” was performed only once, in the 2010 Beijing International Music Festival. John Adams’ music is certainly known in musical circles, but minimalism is not widely appreciated or performed. Indeed, Adams’ music is technically quite difficult for most Chinese orchestras, who are unaccustomed to such unconventional rhythms.

But the most important reason “Nixon in China” has yet to be staged in China is a simple one: plain old politics. The Communist Party is the official keeper of history and it does not tolerate deviant versions, even those clearly in the realm of fiction or fantasy. Instead, the Party reserves the right to tell its own stories – especially if high-level leaders are involved. Indeed, any film or stage production that involves a Chinese leader (who will almost certainly be deceased to be the subject of such a story) must be vetted by numerous bureaucracies and concerned powers-that-be. By the time such vetting is done, all the inter-personal drama will have been scrubbed unless it is needed to support the historic record – you can depict Mao arguing with a political foe, but you’ll never see him arguing with his wife. Indeed, you’ll hardly ever see his wife, unless she’s at the Communist base camp of Yanan in the pre-1949 years – and you’ll certainly never see her singing “I am the wife of Mao Tse-tung…at the breast of history I sucked and pissed…thoughtless and heartless, red and blind” as she does in the opera. Poetic license is not permitted when it comes to the Communist Party (unless it is taken, unacknowledged, by the Party itself).

This said, the time will come when China will stage “Nixon in China” – and it may be sooner rather than later. Puccini’s “Turandot” is another opera that everyone long wanted to see in China, simply because it is set there – but for decades it, too, was deemed unacceptable. Puccini was seen to have “stolen” Chinese musical themes and the story was considered absurd and disrespectful to China’s culture. Indeed, when it was finally staged in full for the first time in Beijing in the mid-1990s, the setting was changed to a mythical nation in Central Asia because it was believed that Chinese audiences wouldn’t accept an opera about such an “unfilial” Chinese princess, even an imaginary one. Fast-forward fifteen years and “Turandot” is the go-to premiere opera production for seemingly every new opera house in China. Not only has the opera been accepted, it has essentially been reclaimed, reinterpreted as Peking and Sichuan opera and even performed in the Olympic “Bird’s Nest” stadium as part of the celebrations for the 60th anniversary of the People’s Republic.

With opera houses mushrooming across China and foreign opera companies increasingly inquiring about the possibility of staging “Nixon,” it is only a matter of time before some daring (or desperate) Chinese opera house takes on this contemporary classic. Odds are it won’t be in Beijing, the center of political power – but it will happen.

Why isn’t NIXON IN CHINA staged in China?

For the same reason that nothing will ever be staged in the Maoist Madhouse – because it’s a THUG state run by Communist Automaton Crooks with brains the size of peas.

I feel sorry for the people of China. They are cut off from the rest of the world by the primitive neanderthal Maoist thugs who rule in tyranny over that country.

You think operas matter to these filthy murderers? You’re very naive. Firstly, Chinese leaders hate foreign culture in every respect. They would never stage an American opera. And secondly, while you have pig-headed thugs who machine-gun monks in Tibet running the country, I hope John Adams would deny those Maoist THUGS the chance to stage his opera.

Dear Neil,

Thank you for your response. As you might expect, we don’t agree.

Opera does indeed matter to the Chinese government, and to the Communist Party, and has for many years.

Indeed, operas were composed – with Communist Party support and encouragement – back in the 1930s and 1940s at the Communist base camp of Yan’an. One of these operas was “The White-Haired Girl,” by the composer Ma Ke, a student of the composer Xian Xinghai (who studied at the Paris Conservatory with Paul Dukas). Mao Zedong – whom I suppose we could call the chief “Maoist” of them all – attended the performance and even offered critical advice. (Ok, his suggestion was that the landlord character should be killed in the end.)

During the Cultural Revolution (1966-76), Mao – with a great deal of encouragement and support from his wife, Jiang Qing – again focused on opera. Massive resources were devoted to creating so-called “revolutionary model operas;” these were not the Western-style operas of our conversation, but they did include two model ballets (one of them based on “The White-Haired Girl) and two model symphonic works. Western musical instruments were used in all the model operas, even those that were essentially Peking opera. Many people who lived through this period – including Jindong – would argue that the Chinese government of this time cared far too much about opera, not too little.

It is fair to say that during the Cultural Revolution, most foreign culture was “hated;” that is, officially forbidden, and those who practiced it – including many musicians – often came under intense pressure. Some were driven to suicide and a few outright murdered. But traditional Chinese culture received the exact same treatment – the goal of the Gang of Four and the Red guards was to “Smash the old and build the new” and this included old Chinese culture as well as old foreign culture.

The Cultural Revolution period was an aberration – as soon as it ended, China opened its doors wide to foreign culture once again. In recent years, as the nation has grown wealthier, this has included a boom in opera house construction. Indeed, 40 or 50 stunning new opera houses have been built around the nation in recent years. Western operas are standard repertoire; if few American operas have been performed, that is because the preference is for romantic opera rather than contemporary. American singers are regularly featured in Chinese productions of such standards as “Turandot” and “Tosca.” China has even started a program to train American and European opera singers in Chinese so that they will be able to sing new Chinese operas in Mandarin! And the program is quite popular – young Western singers see the mushrooming of opera houses in China, the number of new productions, and the growing interest in opera from a young, educated audience and they see one thing: opportunity.

Here are a few relevant links if you are interested:

Boom Times for Opera in China http://www.nytimes.com/2010/12/21/arts/21iht-chinopera21.html?pagewanted=all

Turandot: Beijing ‘reapproriates’ a Puccini opera

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/03/25/arts/25iht-melvin.html?pagewanted=all

China National Center for the Performing Arts (which is running an opera festival right now)

http://www.chncpa.org/ens/

I agree that it would be a good thing to stage operas such as Adams’ Nixon in China and Tan Dun’s The First Emperor in the PRC. Certainly, the sky did not fall down after Turandot started to be performed in China. Might the Party’s Bureau of Propaganda and other parts of the party-state’s control apparatus someday take their cue from the openness to cultural activity during the cosmopolitan Tang dynasty instead of the mid-Qing literary inquisitions of the Yongzheng emperor and the Qianlong emperor?

Good question, but I don’t have the answer, except to hope. The First Emperor has actually been broadcast in China, in a movie theater setting as is done here; I think it not being performed in China is really a cost issue, rather than content. If I had to bet, I’d say Nixon in China will be staged by its 50th anniversary. But the real hope is that China will one day produce works of the same caliber that can be shown around the world – to do that, however, requires more openness, as you say, and more leeway with the presentation and interpretation of history.