Today is Qingming, the 104th day after the winter solstice, traditionally set aside for the living to honor the dead. Qingming is a national holiday in China, which means that urban traffic lessens dramatically and (this year, anyway) the skies clear accordingly. More than 520 million people are reported to have gone off to sweep the debris of winter from the tombs of loved ones – and when they were done, many took the time to enjoy themselves in the world of the living.

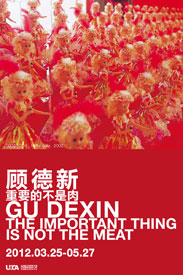

So it was that beneath Beijing’s cerulean skies, tens of thousands of young people crowded the 798 Art District, sipping coffee in its abundant cafes, browsing its ever-trendier shops, and occasionally even wandering into its countless galleries. Among the exhibitions from which they could choose was UCCA’s exhaustive retrospective of the works of Gu Dexin, “The Important Thing is Not the Meat,” which runs until May 27.

The works on display in this one-of-a-kind show were created by Gu between the mid-1970s and 2009, and thus follow the arc of China’s discovery of, and entry into, the contemporary art world. There are early paintings on wooden boards (canvases then being too expensive for a young artist) and early installations of colored plastic molded into shapes resembling internal organs. (Gu’s parents worked in a plastics factory, as did he for a time.) The pieces of meat painted in early still lifes become real pieces of meat in later installations. Works that are imitative, if skilled – like cubist paintings – give way to strange, but compelling, paintings of multi-breasted creatures and pink clay sculptures of hermaphrodites. Bushels of real apples surround a fallen flagpole and a piece of farm equipment, their pungent smell permeating the massive hall. The works get bigger, more ambitious, smellier – and then they stop.

Indeed, if Gu’s career has traced the trajectory of contemporary art in China, it has at the same time rejected it. Almost none of his work is recognizably “Chinese.” There are no Mao paintings, no riffs on socialist realist art. His concerns appear to be more universal and more personal – death, decay, the innumerable possibilities of life.

And, as of 2009 – when Gu announced that he would end his career as an artist and return to “normal” life in the house where he grew up – he has rejected not only the “Chinese-ness” of so much contemporary art but the making of art altogether. His last work, included in the exhibition, consists of fake windows through which puffy white clouds can be seen scudding across a blue sky; two massive billboards printed with red characters; and an engraved stone stele. The billboards carry repeating sentences – “We have murdered women. We have murdered old people. We have murdered children. We have eaten human brains.“ – that call to mind Lu Xun’s story “A Madman’s Diary”(published 1918) in which the narrator comes to believe that he is surrounded by cannibals, and that even his sister was eaten by his brother. The last words of Lu Xun’s famed work are “Save the children….”

The last words of Gu’s last work, carved twice in red in the stele, are: 我们能上天堂, We can go to heaven.

Leave a Reply