I was so pleased to get back to Call Time after some time off (for both work and pleasure) and to get to come back to it with the amazing Jack Viertel. As some of you might know, Jack was one of my original guests on Call Time when it was in its infancy as a YouTube show. Some of you might also know that Jack is one of the greatest theatre minds we have these days, as responsible for shaping the landscape of late twentieth/early twenty-first century musical theatre as, say, Jason Robert Brown, George C. Wolfe, Susan Stroman, or Andre Bishop. Jack was the Artistic Director of City Center’s Encores! for nearly two decades, successfully reviving such shows to which NY audiences wouldn’t have otherwise been exposed like House of Flowers, 70, Girls, 70, No, No, Nanette, Little Me, Paint Your Wagon, The New Yorkers, and many more, to say nothing of the lesser-known gems that went on to successful Broadway runs under his tenure, including The Apple Tree, Finian’s Rainbow, Sunday in the Park With George, and of course the 2008 revival of Gypsy.

If that wasn’t enough, Jack spent three decades as the Creative Director/Senior Vice President of Jujamcyn Theaters, the organization which today owns five of the 41 theaters which make up the district and market known as “Broadway” today. In reality, this meant that Jack had a major hand in bringing some of the most well-known and important Broadway shows of the last decades to global audiences: Jack was either a creative advisor/consultant to, a producer on, or, in many cases, both for shows like Hairspray, City of Angels, The Producers, Dear Evan Hansen, Angels in America, six August Wilson plays, and, most recently, The Outsiders, which won the 2024 Tony award for Best Musical. Some of you might also know that Jack distilled this breadth of knowledge, as well as some of the core tenets of musical theatre, which he had been teaching at NYU (the so-called “I Want” song, the conditional love song, the actor two opener, etc.), in his 2016 nonfiction book, The Secret Life of the American Musical. The book is excellent, a favorite among musical theatre scholars, fans, and nerds alike, and it’s also a NY Times bestseller.

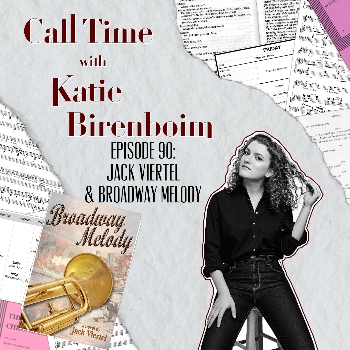

Next, instead of writing, perhaps, a deeper dive into the “history of the American musical” or a “celebrity biography” (as many people suggested, he tells me on the show), he turned to a surprising creative outlet, and wrote a novel! It’s not like he pulled random characters, settings, stakes, or themes out of a hat, however. Broadway Melody, Jack’s first novel and second book, is, much like The Secret Life…, a composite of his decades on Broadway and beyond: not only of the knowledge he’s gathered at the helm of countless Broadway shows, successful and otherwise, but also of the stories he’s been told, and the relationships he’s made, in this big, wacky business. Broadway Melody seems to have everything: spanning almost an entire century, the novel focuses on a love triangle between a longtime pit musician and orchestra “contractor” (the person who hires all of the musicians for a Broadway show, negotiates with the union, etc.), an electrician, spot-op, and union leader, and an actress. But the central love story is only half of the bargain.

The novel focuses on love, yes, but, as I say on the podcast, it’s also a love letter to a few things beyond romantic relationships. It’s a love letter to friendship, and the complicated ways that friendships can grow, change, and evolve over many years. It’s a love letter to Broadway, and the musical theatre business. Indeed, one of my favorite things about the novel is that most of the characters, with the exception of an occasional cameo from a very famous, real person like Stephen Sondheim, Jerry Herman, Hal Prince, or Joe Papp, are some of the many, regular people who, like magic, make a Broadway show go up every night — sometimes twice!

Jack tells me on the podcast that in some ways he wanted the novel to be a tribute to those many people “who show up in the building every night to make these things happen.” “If you’re just an average theater goer,” Jack continues, “even an ardent average theater goer, you don’t even really think about the fact that these people exist. You watch the people on the stage, you read the biographies of the writer and the director,” forgetting, he guessed, the carpenters who were there at 8 am for crew call to ensure the prop door for the farce works, the electrician who had to re-rig a set of lights during the tech dinner break, the stage crew who have to stay every night and mop up the confetti littering the stage at the end of Six, the dresser who has worked with the star for fifteen years, and knows exactly what drink to hand her before “Defying Gravity,” the assistant company manager who just got in from Columbus, Ohio and has been asked to negotiate with a top-tier CAA agent. Those are the people who populate every page of Jack’s wonderful novel, and, indeed, some of them hit major success — the actress wins two Tony awards — but many of them never get the credit, recognition, or monetary reward. It’s their passion, but it’s also their job, and they show up for work every day, and see where the day, month, year takes them.

“I definitely wanted to put the hit: flop ratio out there,” Jack tells me on the podcast, “and also tell a story of someone who is in a couple of really successful shows, wins the Tony Award twice for Best Actress, but isn’t a star. She never becomes, say, Barbra Streisand. She had long periods where she doesn’t work at all.” Good times and bum times, I’ve seen them all, and, my dear, I’m still here. “[I wanted] a nuts and bolts feel for what a career spent between 41st Street and 53rd Street was actually like,” Jack tells me. Not only do you get that “feel” to which Jack refers, but the novel hones a deep respect and admiration for the not-quite-stars of the stage, the people who are able to “make a good living” in this ephemeral, mercurial business. One character in the novel says that “hearts break every night [in the theater] and put themselves back together again before the matinee.” Indeed, Broadway Melody hammers home the fact that making a life on the stage — in any capacity — requires grit, determination, grace, humor, and a certain survival instinct. No matter what’s going on in your life — onstage or off — you have to pick yourself back up and sing that opening number at 2 pm. The show must go on.

I also note on the podcast that I see Broadway Melody as a love letter to late twentieth century American history. Indeed, I tell Jack on the show that his novel has some sort of Forrest Gump-y qualities. Just as Forrest shows up at the Vietnam War, Watergate, and the economic opening of China, so Broadway Melody‘s characters flee World War II, experience the AIDs epidemic, homophobia, and other bigotry, and watch as Times Square disintegrates and is resuscitated. Jack tells me that he did feel it was necessary to refer to the fact that most people who make a life in the theatre are “fleeing” something, whether it’s their parents, their church, their home, what have you.

“I wasn’t going to shy away from what is obvious about Broadway, which is that it has always been a respite for people who don’t fit in to conventional life in one way or another,” Jack tells me on the show. “There are lots of different ways to not fit in, but so many people who come to the theater in New York to work, not necessarily as artists, as company managers, or box office treasurers, are people who essentially fled there, fled to get there. From wherever they were, from the Midwest, from Europe, from some place, from some parents they couldn’t stand, from churches they couldn’t stand, whatever.” Jack’s novel is a major testament to that fact, and I find that consistent with the Forrest Gump-y, historic, epic qualities of the novel. As I say on the podcast, I would even put it in the tradition of some of the great American epic novels, novels that take apart, examine, and put back together the American Dream. Broadway Melody, for example, is a lot more tender-hearted, and with a lot rosier of a view of American life, than, say, Roth’s American Pastoral, or the excellent Long Island Compromise by Taffy Brodesser-Akner, but they all tell sweeping, epic, inter-generational stories about America and its culture. After all, a story about people who “fled” to New York for Broadway, who never really felt accepted, seems as “American” a story as you can find. “Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free…” seems to me the same credo as “NYC/Just got here this morning…Up there/In lights/ I’ll be.”

In much the same way that Broadway Melody is a love letter to the forgotten actors in the business and an essentially “American” epic, it’s equally a love letter to New York City (the “fifth lady” as Sex and the City scholars would say). Indeed, it’s an “American epic” in the sense that the history of the late twentieth United States is told through the prism of New York, and, even more specifically, midtown Manhattan. And, importantly, and again something that ties it to the other epics of late twentieth century American life, it’s a midtown Manhattan that’s largely been lost. Indeed, one of the main characters, Ike Horowitz, spends almost the entire first chapter lamenting the loss of various midtown/Broadway hotspots and landmarks. He thinks of Hawaii Kai, a restaurant just over the Winter Garden theater, that closed in 1989 but had enjoyed quite a storied history on Broadway and something of a cult following (a scene from Goodfellas was shot there!). He thinks of Bond Clothing Store, which was apparently known as the “Cathedral of Clothing” until its closure in 1977. Since then it’s housed a restaurant, a famous The Clash concert (1981), and an Old Navy.

A large portion of the book is devoted to some of the characters’ involvement in the push to save a series of five Broadway theaters — the old Helen Hayes, the Morosco, the Bijou, the Astor, and the Gaiety — from demolition to make room for the Marriott Marquis.

Ike also laments the closure of The Colony record store, a NYC landmark that even I remember fondly: growing up in New York, and being obsessed with musical theatre basically from birth, I still remember my parents taking me to The Colony virtually anytime we were in midtown or going to see a show. I was fascinated by, what seemed to me, the hallowed halls of the place, a space where you imagined Barbra Streisand, Bernadette Peters, or (my favorite as a child), Sutton Foster had picked up their sheet music for their very first auditions. It’s where I got the sheet music to learn some of my very first musical theatre repertoire, where I got the CDs I played so often in the car they grew worn and tattered (Guys and Dolls 1992 version, The Producers OBC, Annie Get Your Gun 1999 revival, Company OBC, Gypsy — Tyne Daly version, and many more). It’s the kind of two-word mention in a book that conjures a place, a time, and an era with exactitude, and totally stops your heart in the process.

It might just be because I’m prone to nostalgia as a person, but I felt like that through reading much of Jack’s book. It left me wondering — and it’s a question I’ve been asking myself often, even before reading the book: do we think people in the future will feel about making theatre today, the way we feel about the theatre, the Broadway, the midtown Manhattan of yesteryear? In other words, it’s hard to feel nostalgic about an Old Navy. I ask Jack this very frank question on the show, and he has the grace to assure me, first, that people will always be nostalgic for the past (“because they always have been”), and, second, that, despite the ways that theatre, or the neighborhood in which we make it, has changed, he has a great deal of hope, and excitement, about the future. “When I was growing up in the early sixties,” Jack tells me, “basically musicals were all alike, they were all what was called the ‘tired businessman’s musical,’ and whether it was How to Succeed in Business or Hello, Dolly!, for the most part, they had a certain tone to them, which was that they made merry for two and a half hours. In recent years, and for good reasons, I think, almost anything can become a musical. In those days, Dear Evan Hansen would have been a play. Fun Home would have been a play. They wouldn’t have been musicals. No one would have even conceived of doing them as musicals…Now there’s literally no limit to what you can musicalize and the music can be as pop rocky as a Six or as serious as Days of Wine and Roses.” “No one’s going to say, how dare you do this as a musical,” he continues. “And I think that’s a really gratifying thing….when I was in college, there were no resident theaters doing musicals. The Old Globe didn’t do musicals. Now they do because the musicals are smaller and they take themselves more seriously…it’s a hugely broad range. And I think that’s really exciting.”

Broadway, both the genre and the location, is very different now than it was in 1950 or 1970. Jack describes it today as “a wide open door. “And I think it’s because the audience has changed and artists have changed,” Jack says on the podcast. “And I think Stephen Sondheim did open that door a good distance by himself, but a lot of people rushed through when the door was open.” Just like our ever-evolving, mercurial city, change is the only constant. And as another starry-eyed New Yorker, Kathleen Kelly (of You’ve Got Mail), once said: “it’s a tribute to this city: the way it keeps changing on you.” The way it evolves. I, for one, think that’s a very good thing.

Listen to my whole podcast with Jack Viertel on his amazing book, Broadway Melody, here. And you can purchase the book on Amazon, or at any local bookstore.

Leave a Reply