About a month ago, Michael Paulson wrote an article for The Times about an unexpected “bright spot” in the American theatre landscape. “Broadway is struggling through a postpandemic funk, squeezed between higher production costs and lower audience numbers just as a bevy of new shows set sail into those fierce headwinds,” Paulson began. “At the same time,” he wrote, “New York’s Off Broadway nonprofits, long essential seedbeds for many of the nation’s most acclaimed playwrights, are shedding staff, programming and even real estate. But there is an unexpected bright spot this season. Commercial Off Broadway, a small sector of New York’s theatrical economy and one that has for years been somewhere between difficult and dormant, is back in business.”

Paulson goes on to highlight the many different productions, theaters, and theatre people responsible for this breath of fresh air in the industry: Cole Escola’s record-breaking Oh, Mary! at the Lucille Lortel (which is transferring to Broadway June 26), Max Wolf Friedlich’s new play Job (which also just announced a summer Broadway transfer), Oliver Roth and Jack Serio’s “loft space” Uncle Vanya, Audible’s purchase of the Minetta Lane (which is currently running Laura Benanti’s solo show, Nobody Cares), Eddie Izard, Daryl Roth, and many more.

This is a trend that I had been noticing for several years: arguably, it all began with the success of Little Shop of Horrors at the Westside Theatre, which opened in October 2019. I remember when the show was announced I kind of couldn’t believe my ears: Michael Mayer? Christian Borle? Jonathan Groff? At the Westside Theatre (“upstairs”)? I couldn’t understand how the production had been able to get such a high-profile group of artists — who, between them, have three Tony awards — to agree to what people saw as a “low profile” gig. This was, of course, how we thought of Off-Broadway pre 2020, especially the type of Off-Broadway for which I didn’t even yet have a name: not Second Stage, not Manhattan Theatre Club, not even Playwrights Horizons, just “random,” as I’m sure it was described somewhere on Theatre Twitter back in the day (if you’re unfamiliar with Theatre Twitter, I don’t suggest you go searching: it’s a dark place and it’s really only for the heirs of the BroadwayWorld message boards). This was, of course, before I went to grad school and began to study theatrical financial structures, but even then I also had questions about the essential premise of the show’s profitability. “If Little Shop wasn’t backed by a nonprofit organization, with the support of a subscriber base and the understanding that ticket sales actually have very little impact on the big-picture budget, how did the producers expect to make back their investment?” I wondered.

The joke was on me of course: Little Shop of Horrors is still running today, continually garnering new, exciting, often celebrity, casts (people like Constance Wu, Corbin Bleu, Andrew Barth Feldman, Jinkx Monsoon, Maude Apatow, Brad Oscar, Darren Criss, Evan Rachel Wood, Sarah Hyland, and Skylar Astin have all taken over Little Shop roles since the original company took their final bows) and critical acclaim. And while commercial Off-Broadway productions are more difficult to track financially than, say, a Broadway production or, of course, nonprofit theatre budgets which are by definition a matter of public record, evidence suggests that this production of Little Shop has been hugely successful financially. “As of January 2023,” Philip Boroff wrote in Broadway Journal, “the production paid out $3.1 million in profit. It had another $1.4 million in member’s equity — assets less liabilities. That suggests investors at least doubled their money, an impressive feat off-Broadway, where commercial success is rare.” Of course, Boroff observed this over a year ago, before people like Maude Apatow and Jinkx Monsoon stepped into their roles and before another round of impressive ticket sales, and we can therefore imagine that the production has continued to make money both for its writers and for its investors.

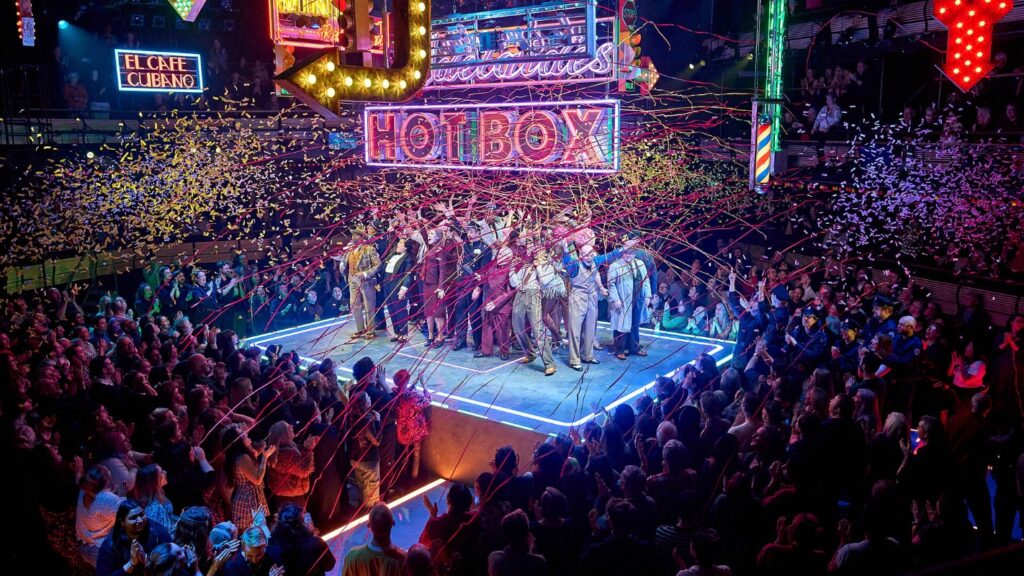

From Little Shop, the astute observer can point to the success of Titanique, which opened at the Asylum Theatre in June 2022 before transferring to the Daryl Roth, where it continues to run today. While Titanique producers have not made a statement about recouping, ticket sales are averaging $100,000 to $150,000 as of February 2024 — a healthy profit for a show that’s been running almost two years Off-Broadway, and one that, pre 2020, would have been largely unheard of. Couple that with the shows that have made less of a profit, per se, but just as much of an impact, artistically and otherwise, on the New York theatrical landscape, Eddie Izard’s Hamlet, Oliver Roth and Jack Serio’s Uncle Vanya, Julia Masli’s Ha Ha Ha Ha Ha Ha Ha at the SoHo Playhouse, and more described above, and you might say that downtown, Off-Broadway theatre is “back” or, as I would describe it, in a new, exciting “Golden Age.”

As Paulson explains in his article, “a vibrant commercial Off Broadway sector existed decades ago, but it shrank as the nonprofit theater movement grew, providing a home for adventurous art. It also contracted as Broadway surged, providing the temptation of bigger audiences and higher profits, and as some venues were lost for more lucrative real estate uses.” He also explains that “[i]n more recent years, there have been some successes — long-running entertainments like Blue Man Group as well as a stream of television parody shows, murder mysteries and other fun-night-out shows that straddle the worlds of comedy, magic, nightlife and theater,” but that the crop of shows currently responsible for what I’m calling the new “Golden Age” of commercial Off-Broadway theatre are all marked by the “promise of an intimate experience…a hip neighborhood…and some kind of intangible quality of authenticity.” As a result, “the audiences are often younger, more local and more diverse than those on Broadway,” Paulson concludes.

He also argues that these commercial, Off-Broadway ventures tend to make sense economically because they don’t deal with the same exorbitant production costs as those on Broadway (“Oh, Mary!, which has five actors, period costumes and several set changes, cost $1.2 million to capitalize Off Broadway,” Paulson writes, “By comparison, The Shark Is Broken, a three-character comedic look at the making of Jaws that was set entirely within a small fishing vessel, cost $5.15 million to capitalize earlier this season on Broadway.”). Paulson also points to the fact that, because of the dire financial straits in which most theatrical nonprofits currently find themselves, especially those without their own Broadway houses, there are fewer opportunities for artists to produce their work in those contexts. Indeed, if nonprofit orgs are shedding staff and even seasonal slots, how many opportunities can there be for new and exciting work, the kind of work that was supposed to define “Off-Broadway,” nonprofit, commercial, or otherwise?

I would argue that there are some other factors at play as well. Broadway is Broadway, and, especially in the postpandemic “funk” to which Paulson refers in his article, and which I’ve written about before, only shows that are either tried and true (Hamilton, Wicked, The Lion King, Aladdin, Harry Potter and the Cursed Child) or boast celebrity casts (Chicago, Merrily We Roll Along, Moulin Rouge, arguably a play like An Enemy of the People or Appropriate) have much of a chance financially. The nonprofits, both on Broadway and Off, seem to be doing even worse financially, and are shedding staff, seasonal slots, and even real estate like wildfire. What’s more, many of these Off-Broadway, nonprofits, for better or for worse, have a great deal of bureaucracy, with many stakeholders both within and outside of the organization with which the artist, the producer, and the production must contend. Perhaps an article for another time, but I’ve definitely gained the sense, since the pandemic, that NY nonprofit theaters are trying to be all things to all people: attempting to appeal to their older subscriber base, a newer, younger, more diverse audience that does not yet frequent their theater, NY Times theatre critics, past, present, and future donors, and, yes, “Theatre Twitter,” all at the same time. Arguably, this is always the job of a theatre, or arts, organization, which must always find a way to both attract and maintain donors and audience members, but I would argue that this indelible truth has had a strong effect on the art itself produced at nonprofit organizations since the pandemic, wherein some plays and musicals start to feel like they were written by committee.

Commercial Off-Broadway productions only have two groups to which they must answer: their investors, and the market. While those are some pretty big-picture subsets, I would argue they make the production of new, exciting work easier on both a financial and an artistic level.

First, on a financial level, commercial, Off-Broadway productions, by virtue of their smallness, are able to be more nimble and flexible than either a big, bloated Broadway production or a show done within the context of a large, bureaucratic, nonprofit theater. I have long compared commercial theatre to tech startup culture — and I think that’s even more true Off-Broadway than On. If you’re small, light, and nimble, you can look for more exciting, more adventurous, and more interesting financial structures that actually shore up your production and make for a better investment. In other words: Off-Broadway, less is more.

When I was in London in spring 2023, for example, and I saw the immersive Guys and Dolls at the Bridge Theatre, I was surprised and excited to learn that Nick Hynter and Nick Starr — or, “The Two Nicks” as they’re known on the London theatre scene — who had both come from running the National Theatre, had raised almost all of the Bridge’s construction costs entirely from VC funding. I was particularly interested in this financial approach, as it hadn’t really been explored before, on either side of the pond. Indeed, VCs are particularly interested in “scalable” (often tech) solutions. Nevertheless, as Alice Saville wrote in 2017, the Bridge management realized that, in today’s world, theatre, much like film, can be “infinitely scalable,” and, therefore, a “world-class investment,” even for venture capital firms. And while this VC funding was used for the construction of a theatrical space itself, rather than the production of one particular show, it nevertheless points to the fact that commercial, Off-Broadway, or Off the West End, enterprises have the flexibility, sustainability, and promise to explore interesting, new, and fresh financial structures for success.

Second, I believe that commercial, Off-Broadway productions offer more artistic integrity and opportunity. As discussed above, success on Broadway these days seems to require either well-known IP (Hamilton, Wicked, Back to the Future, Harry Potter, one of the many jukebox musicals) or celebrity casting. I believe that nonprofit theaters, both on and off-Broadway, are to some extent artistically flailing postpandemic: trying to be all things to all people, maintain their subscriber base while reaching a new audience, and pleasing both theatre critics and theatre Twitter to boot. Within that context, it’s no wonder that the art can start to feel flat, dull, pedantic, or unexciting. A commercial, Off-Broadway production is small and it’s one shot, one show. That helps from both a financial perspective and an artistic one. The playwright, producers, director, designers, and actors have to think about one goal and one goal only: telling the story. Arguably, that should always be the artistic objective for a play, on Broadway, Off-Broadway, or at a nonprofit theatre, but, in my opinion, it’s easy to lose sight of this target in the thick of nonprofit bureaucracy or when faced with a multi-million dollar Broadway budget.

Furthermore, given the dire economic straits on Broadway and at the nonprofits, there’s a sense that only well-established, older, or even famous artists and theatre makers are given a chance. I’ve been speaking with younger generation theatre talent for years who have felt frustrated: “I’ve been working so hard, why not me?” seems to be the prevailing attitude. Indeed, it used to be that a thirty-something-year-old was considered mature enough to work On or Off-Broadway, but today there are the endless fellowships, associate stints, and hoops to jump through first in order to ensure that you, as an artist or theatre maker, are “worth the investment.” I would argue that many of these successful Off-Broadway, commercial productions like Uncle Vanya, Ha Ha Ha Ha Ha Ha Ha, Oh, Mary!, and more have only been possible because young, excited artists have grown frustrated, thrown up their hands, and said, “well, if someone won’t give me a chance, I have to take it myself.”

Paulson fails to note in his article that part of this “boom” in commercial Off-Broadway theatre has been a direct result of young director/producers who have been emboldened to strike out on their own, take a chance, and be more than one thing. As someone who has long believed in, and worn, many different hats in the theatre — something that is controversial even today (I’ve had so many people ask me “well, which are you?” or say “people will get confused…you have to pick one) — this is excellent news. It’s consistent with the thesis of Call Time with Katie Birenboim: I have long believed, but particularly since the pandemic, that the future of theatre lies with the multi-hyphenate artist, the artist who does, and is excited by, more than one thing. I believe that commercial Off-Broadway’s “New Golden Age” is the first fruits of that labor.

Sound off in the comments and let me know what you think! No matter what: it’s an exciting time to be attending, writing about, or making theatre in New York City.

The Cherry Lane Theater is closed. The Orpheum remains dark after a brief Eddie Izzard run. The Duke has not had a show in 4-5 years. The Signature is only doing 3 productions this year and mostly trying to rent its theaters to other producers, the 46 Street Playhouse at St. Lukes remains dark, Saint Clements remains dark over a long stretch, the Westside downstairs has been empty for years, and so on. Off Broadway a bright spot? Hmmmmnnnnn….. And only a million (plus) dollars to produce at the Lortel …. 3 mil being lost with the new rock musical at New World Stages…and another 3 million was lost on Americano a couple of seasons ago….

Is off-Broadway commercial actually humming along? At least Forbidden Broadway will be returning to off-Broadway in August… where it belongs.

Appreciate this comment, and love the spirit of debate. I will point out, however, that the Signature is a nonprofit (and therefore outside the scope of the thesis…in fact, the article talked about the degree to which nonprofit theaters off-broadway are struggling). The Cherry Lane was bought by A24…yes it hasn’t produced anything yet, but if the Minetta Lane Theatre’s purchase by Audible is any indication, it will surely produce interesting, thought-provoking, and potentially lucrative work. It’s also important to note spaces like The Connelly — super successful run of Kate Berlant’s show and Animal Kingdom, SoHo Playhouse, even Theatre Lab. Many other examples in this article plus Michael Paulson’s: https://www.nytimes.com/2024/04/11/theater/off-broadway-oh-mary-eddie-izzard.html. I do think there’s a distinction to be made, however, between commercial off-broadway spaces in midtown (New World Stages, the Westside), and those downtown, where, as noted in the article, the proximity to “hip” restaurants, bars, and the general neighborhood is a big sell for ticket buyers and young producers alike.

A wonderful article, beautifully written and clearly expressed!!! I have always enjoyed Katie Birenboim’s writings—-always thoughtful, always well-said, and dealing with interesting issues in the theater!