For my last podcast of 2023 (!!), I had the absolute pleasure of chatting in-person with renowned set designer Wilson Chin (Cost of Living, Next Fall, and Pass Over on Broadway; Lincoln Center Theater, Roundabout, the Public, Second Stage, and more; Lortel and Drama Desk nominations). Early in the podcast we mention that Wilson and I “kind of” worked together/kind of didn’t: by that we mean, Wilson designed the set for the National Tour of Annie, but because I only came aboard the project for Year Two, I didn’t tech the show with Wilson or even work with him directly at all. We eventually met through the grapevine, however — the “grapevine” being the wonderful Jenn Thompson (friend of the pod) and Philip Rosenberg — and we got on like a house on fire (or however that saying goes).

I’ve had a set designer on the show before (designer Beowulf Boritt), but I love to interview multiple designers, because everyone’s approach to the process is different, and because I know so little about the actual work that I am fascinated and astounded by nearly everything. For example, Wilson describes on the podcast how, after meeting with the playwright and the director several times, and, if it’s an old play or musical, doing research on what previous imaginings of the world of the play have looked like, Wilson works primarily with three dimensional models: starting with a “white” model, so that he can think “just” about “space and volume” rather than “color and texture” before moving on to drawings, much like architectural renderings. Wilson describes his “style” as “architectural” rather than necessarily “pictorial or illustrative.”

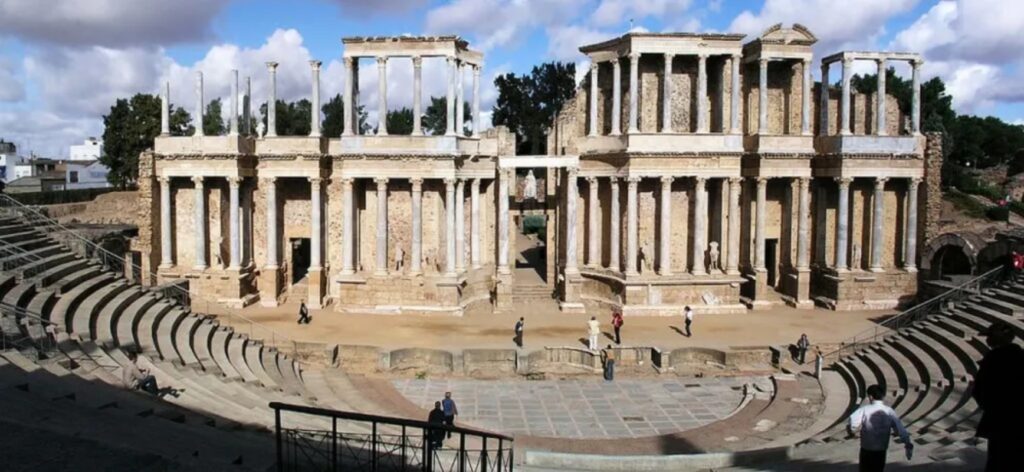

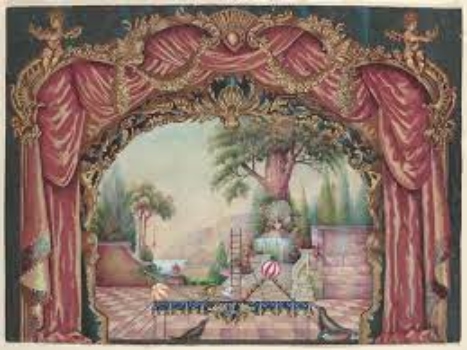

Indeed, as part of our discussion, Wilson and I dip into the history of theatrical set design: as Wilson describes it, in the past, “sets” were primarily perceived as “painted backdrops” made to “resemble a three-dimensional surface or vista,” into which actors walk on and through. In fact, theatrical sets date all the way back to Ancient Greece and Rome, when Greek thespians “used the architecture of the theater itself to create a background” while adding elements like wagons, cranes, and even elevators and ramps (by the time of the Romans). John Bagby, Theatre Department Chair at SUNY Oneonta, tells us that, from there, the most important innovations in theatrical design came about during the Renaissance, when painting techniques that created a sense of depth on a 2-D surface (otherwise known as “perspective”) led to the first true theatrical backdrops. These were heavily used in vaudeville, Golden Age Hollywood films, and opera and dance — indeed, Wilson tells me on the podcast, he knows from his time as the associate for world-famous set designer Santo Loquasto that ballet dancers to this day call their sets “backgrounds.”

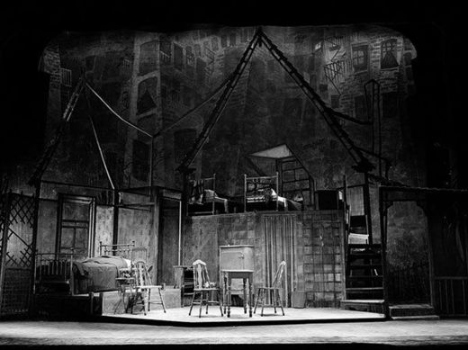

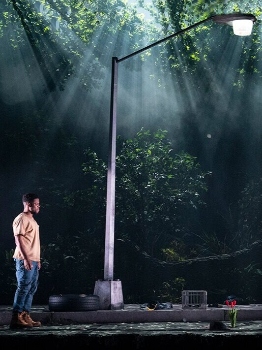

Wilson, however, thinks of his sets as more like “foregrounds.” “I design obstacles for the actors,” Wilson tells me, “whether it’s a door, a wall, furniture, I don’t design things that are in front of them. I design things that are in their way.” This perspective is consistent with the evolution of theatrical set design, which veered away from its operatic, dance, vaudevillian, and burlesque forebears in the 20th century with prominent designers like Adolphe Appia in Switzerland, Gordon Craig in the UK, and Jo Mielziner in the United States, who pioneered a style which became known as “selective realism” and designed the sets (and lighting) for original Broadway shows like Of Thee I Sing, Carousel, Guys and Dolls, A Streetcar Named Desire, Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, Death of a Salesman, Gypsy, and The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie. Indeed, the McNay Art Museum Staff has argued that Mielziner’s “greatest contribution to American scene design, ironically, was the elimination of as much scenery as possible.” Designing without a painted backdrop, and with very limited furniture, other elements, or merely the “skeleton” of a house, as Wilson tells me was the original design for All My Sons, Mielziner argued is “the most fascinating of all designing. It deals in form that is transparent, in space that is limited.” It makes sense, therefore, that based on the influence of Appia, Craig, Mielziner, and others like them, by the time we got to the 90s, when Wilson was really breaking into the theatre scene, scenic design became, he tells me, about “shocks of color…neither…period nor contemporary; it would be like a made up kind of time period” that leaned away from “realism,” he describes.

Today, much like contemporary art, Wilson tells me, the world of set design has opened up so much — because of all of these innovations, discussed above — that there is no real “trend” or “style” one could describe as typical of “21st century scenic design.” You could have a bare staged Ivo Van Hove show and a Bart Sher revival with a full, hyper-realistic boat sailing on (I’m thinking of The King and I) in the same Broadway season.

For Wilson, as discussed above, what’s most important is the actors’ interaction with, within, and through, his sets. Indeed, just as Mielziner argued that the theatrical set designer “deals in four dimensions…employ[ing] the fourth dimension of time and space,” so Wilson sees his sets as “obstacles” with which the actors must contend at each and every performance. While the painter has figured out how to create perspective and three-dimensionality on a two-dimensional surface, a theatrical set is also able to live in the temporary, ephemeral world of the play (aka time and space). It’s the same set, but it’s reborn anew for each and every performance, where each and every actor might interact differently with it, depending on the day, time, and other factors. “We’re visual dramaturgs,” Wilson tells me on the podcast: “in the beginning of the process, it’s a director and a playwright. And then usually the next person that gets brought in is the set designer. [So in that way] we’re the first person to talk about the play in a dramaturgical [sense],” he continues. “We do play a small part in what that play eventually becomes, and we do influence the writing of it, and the creation of it. That’s actually my favorite part of working on [a] new play…the birthing of it…discovering it together.”

And, indeed, as Wilson and I discuss on the podcast, set design is about much more than simply “servicing” what’s written on the page. A playwright says a character “enters” so there must be a door. But what kind of door? A fancy one? A ramshackle one? Does it work? And, in a truly Mielziner style line of questioning…does there have to be a door at all? Can we just imagine the actor has opened a door of some kind? Does he or she mime it? Are there, therefore, any doors on set? Wilson tells me on the podcast that set designers being additive to the process is the single thing he wished more people knew about what he does. “Before the start of every process, I always ask myself,” he says, “What am I bringing? How do I connect to this play on a personal level? What in my being is why I am at this table?” And the answer might be something like “I grew up in a restaurant,” Wilson tells me, “or…I grew up second generation American, [but] it could also just be something like, I need joy in my life right now.”

In this way, Wilson is able to bring some of himself to every one of his designs, and thereby, act as one of the first “interpreters,” or “dramaturgs,” of the play. And it’s why I felt the need to talk about the history of scenic design so much in our discussion and in this article: Wilson’s process, style, and perspective is consistent with the evolution of scenic design on the whole. No longer are sets merely about reflecting time and place as accurately and realistically as possible. Instead, they’re meant to evoke feelings, tones, themes, impressions, or even theses. One could accomplish that using a hyper-realistic full version of a house or nearly a bare stage with two sets of chairs. I’ve seen both, and both can do the necessary work of telling the audience, and the actors, what kind of world they’ll be in for the next two hours, and how that world might change. As the cast members sing in one of my favorite musicals of all time, [title of show], “who says four chairs and a keyboard can’t make a musical?”).

Listen to our full episode, where we also discuss Wilson’s “gateway” Sondheim musical, networking and gatekeeping, collaboration and delegation, why the British love puppetry, and Zodiac signs. Thank you to my Call Time readers and listeners for an amazing year of growth — if I haven’t already said it enough. Doing these interviews, and writing these reflections, are always the highlight of my week, and I hope you get half as much joy from listening and reading as I do from making them. We have a lot of great things in store for 2024, however, so stay tuned: there’s a great deal going on in the arts space (good and bad!), and therefore it’s going to be a really interesting year of Call Time. As always, if you like what you hear, please subscribe on Spotify, Apple, or wherever you enjoy podcasts, rate, or comment.

Leave a Reply