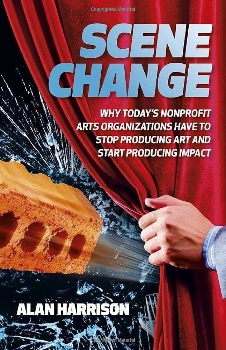

This week marks a very special episode of the podcast, not only because it focuses on a forthcoming book (like the episode on Shy with Jesse Green and that on Broadway Bodies with Ryan Donovan), but also because I got connected with the guest (the author of said book) through Arts Journal! So if you’re an avid reader of the Arts Journal blogs, you might already be familiar with Alan Harrison and his work, and thereby eagerly awaiting the February 1st release of Scene Change: Why Today’s Non-Profit Arts Organizations Have to Stop Producing Art and Start Producing Impact. Regardless, I think I speak for most of us when I say that this represents the Arts Journal crossover event of the century ;).

In Scene Change, which indeed comes out February 1st 2024 but is available for pre-order now, Alan takes what he’s learned in his extensive and varied career in the theatre (Alan tells me on the podcast about his time in the “seventh worst show in New York” — according to The NY Daily News, when he met Jacqueline Onassis and John Kennedy Jr. while working at an early Lincoln Center Theater, and about his time as Managing Director of Alabama Shakespeare Festival and Executive Director of Arts West) and uses it to challenge most of the industry’s pre-conceived notions about theatre-making and art-making. Given how the pandemic has laid bare some very hard truths about theatre and the arts (a fall 2022 survey revealed that revenue from performing arts ticket sales in the US and Canada was down “18%”, “companies were selling 26% fewer tickets than before the pandemic”, and there’s been a “13% decrease in number of philanthropic gifts” across the board), Alan’s thesis is simple but somewhat polarizing: as Keri Mesropov, Former Chief Talent Officer of TRG Arts summarizes in the Foreword, Alan argues that nonprofit arts organizations must truly “earn and honor [their] status as a 501c3 by reflecting and serving the communities [they’re] in and the people that comprise them.”

That sounds all well and good — most arts nonprofits purport to serve their communities — but, as Alan argues in the book, living that out in practice means making some very real and tangible changes to most arts organizations’ hierarchical structures, programming, physical spaces, visions, and even their missions. Indeed, Alan asserts that most nonprofit arts orgs have things rather backwards: “Art being enough is not the question,” he writes, “Art is enough. But nonprofit arts organizations are not art. They don’t even create art; that’s what artists do. They are charities, in the business of creating positive impact using art as a tool.” In other words, Alan challenges and in actuality takes down the old adage “art for art’s sake.” For him, making “great art” cannot and should not be any arts organization’s mission, with educational and community engagement initiatives shunted off as sort of organizational side projects.

Alan refers to the IRS tax code (oh joy), which does not grant tax exemption status to arts organizations. Section 501 of the IRS Title 26, Subtitle A, Chapter 1, Subchapter F, Part I, Subsection (c), Sub-Subsection (3) mentions “religious, charitable, scientific, literary, or educational” organizations, Alan writes, but not once does it mention the arts. As I learned grad school, this is a big reason why most nonprofit arts organizations have robust educational arms — not necessarily out of the goodness of their hearts: beyond the making of great art, they can always say they “earn” their 501c3 status effectively as an educational organization. And, indeed, as Alan reminds us in the book, nonprofit arts organizations have for years used the same five studies/statistics to justify their missions and visions: kids who did art of various kinds after school tend to ultimately earn higher math scores on standardized tests than kids who don’t. Woo! That is awesome — and I say that without irony — but, as Alan also writes, it’s not a very convincing argument as to why your specific arts organization should exist in the here and now. Alan urges executive and artistic directors to ask several questions of themselves and their organizations: How is my organization serving my community directly and tangibly today? And how is art the best way to enact that change?

I must admit, and as you’ll hear on the podcast, I bristled at the concept at first. Especially because I still see the nonprofit theatre scene specifically as the place to do the experimental, interesting, perhaps controversial art that wouldn’t otherwise be made. If commercial theatre is at the whim of the markets, isn’t nonprofit theatre the only space to produce “art for art’s sake”, I argued? I worried that if missions became too specific, nonprofit arts organizations would jettison plays or musicals that they feel might not make the most positive impact on the community. Take, for example, a play like Angels in America, which we discuss on the podcast. Undoubtedly one of the greatest plays of the twentieth century, and one that we both agreed would not have initially been produced by a commercial producer. “With your vision of how non profit theatre organizations should work,” I argue on the podcast, however, “if the Eureka Theatre Company, for example, is hearing that the biggest problem in the community is homelessness and it’s doing stuff to address that, maybe it wouldn’t have produced Angels in America because it didn’t think that it was properly serving the community and that it was just art for art’s sake. So it’s all well and good that these great artists are the ones who are serving art for its sake and creating whatever they want. But how do they get produced? How do they get supported in an economy in which the only two choices are commercial theater that has to make money at all costs or organizations that are, in your vision, only about serving what the community directly needs? How does a play like Angels in America get produced?”

Alan’s answer is that the nonprofit arts organization — or the industry, for that matter — shouldn’t be so much of a binary. “You don’t have to [always] do the single most important thing that your community needs, but you have to do SOMETHING that your community needs,” he argues. Take the Angels in America and Eureka Theatre Company case again, for example. Let’s say the number one issue facing Eureka at the time WAS homelessness in the San Francisco area. But, undoubtedly, the prejudices, injustices, and hardships facing the LGBTQIA community was also a problem (in 1991, when Angels premiered, 20, 454 people had died of AIDS that year). Using Alan’s vision of the nonprofit arts organization, Eureka could — and should — produce Angels, even though it was tackling one of many problems the San Francisco community was facing, rather than, say, the #1 problem. And, indeed, using Alan’s vision, Eureka could have also thought a bit outside of the box and, in addition to presenting Angels in a more formal way, presented the play in homeless shelters or other such spaces, thereby using “great art” to attempt to make a tangible difference on multiple big problems facing the San Francisco community, in several different ways.

Now: how does Alan argue nonprofit arts organizations rejigger their missions and make these positive changes to the community, exactly? These suggestions might seem even more radical to the arts manager’s ears than his thesis. Like the above example suggests, first and foremost, Alan argues that nonprofit arts organizations should not own their buildings, and, if anything, should follow in the footsteps of the Long Wharf Theatre in New Haven and effectively “get rid of” their spaces. Not only are buildings, especially owning one, a cash drain, Alan argues, meaning that most of the arts manager’s time and energy is actually spent thinking about, and paying for, floods, heating, paper towels, and things like “urinal cakes,” but it’s also not the way to make a direct impact. If you want to affect the people in your community who actually need help, Alan argues on the podcast, “inviting” them to your building is not the way to do it. “Inviting is a horrible word,” Alan told me during our conversation. If you’re serious about making positive changes to your community and earning that 501c3 status, you have to get “creative” with how, and where, you present your art. Alan tells me about an orchestra in Seattle that would perform for a tent city under an overpass — and bring social services with them, so audience members could also get food, a shower, or sign up for Section 8 housing. Alan told me about Out of Hand Theater in Atlanta, which produces shows in homes, schools, businesses, houses of worship, and other public spaces, but specifically NOT in theaters.

In order to give up their spaces and interact more directly with the community they serve, Alan also of course argues that a pillar of these new-and-improved nonprofit arts organizations must be collaboration with, and listening to, actual members of the community. In that regard, when reading the book I thought that Alan’s thesis had quite a lot in common with the part of the arts management field known as “community engagement.” My professor, Donna Walker-Kuhne, who basically invented the formal concept, came on the podcast last year to talk about the importance of being in an ongoing, collaborative conversation with the surrounding community. To Donna, and to Alan, that means engaging with restaurant owners, faith leaders, public school teachers, and other people who can see what the community really needs or wants, beyond the faraway benchmark of “higher math scores sometimes.”

Beyond mission control, true community engagement, and the creative use of space, Alan also preaches pay equity, tangible DEI initiatives — including the release of what he calls “toxic donors” (you know the ones), and a major reorganization of the company’s hierarchical structure. Indeed, Alan argues that the “mission is the boss, not a person,” so the Executive Director should be the true leader of the organization, with the Artistic Director reporting to him or her at the “Director” level (along with the Marketing Director, Development Director, and others). Again — a controversial assertion, one that I’m sure will send arts managers into a tailspin, especially those who remember the origins of the American arts nonprofit scene, when the Artistic Director was the true big cheese. Alan argues, however, that the Executive Director as CEO structure is more consistent with other nonprofit, 501c3 groups. It also fits with his larger vision of the artistic nonprofit: if the art is a TOOL to produce impact, then the artistic director, like the development director or finance director, is also a “tool” in service of the mission.

While, again, this concept might cause many to bristle — it did for me! — it promises to eliminate many organizational problems with which the typical arts nonprofit struggles, including mission creep, lack of legacy planning, and bureaucracy. As I say on the podcast, with equally powerful Executive and Artistic Directors, who both report to, and serve, the Board, it takes twice as long to get anything done at an arts nonprofit. While I have always been of the belief that arts leaders need to be equally adept at the creative side of theatre-making as they are on the business side — I’ve tried to model my career after a Todd Haimes (former CEO/Artistic Director of Roundabout) or a Kate Maguire (CEO/Artistic Director of Berkshire Theatre Group) type — Alan argues that none of his writing in the book is sacrosanct. “It’s not a diatribe; it’s not a polemic,” he tells me on the podcast. And indeed, I’m not sure that every arts organization can, or should, adopt every single suggestion Alan makes in the book (and he makes many!). Instead, I feel the book should be used as an example of what kind of creative, out-of-the-box thinking arts leaders need to be doing if they want to pull the industry out of its inarguable rut.

The stats don’t lie, and, as Alan tells me on the podcast, the pandemic rushed things along, but certainly didn’t CAUSE the many economic and organizational problems nonprofit arts orgs face today. The audience hasn’t been coming — or, frankly, they’ve been dying — for quite a long time. People haven’t been subscribing, and, perhaps most importantly, they haven’t been donating or giving in the same way that their parents or grandparents did. As I’ve written about before on Arts Journal, it’s my belief that the nonprofit arts field has failed to capture the attention of my generation and Generation X (and if we keep going down this road, likely Gen Z as well). Most of the powerful nonprofit arts Boards in NYC have plenty of people in their seventies and eighties, but almost nobody in their fifties or even forties and thirties. And it’s simply not the case that those generations don’t have the money to give/spend — it’s that they are giving/spending elsewhere. As Alan argues on the podcast, this is because art, or rather arts organizations, are not “essential” to them. Your job is to “make it essential to them,” Alan explains on the podcast. And that, in his view, requires being “intentional” about your “impact” as an organization.

As you can see from this article, Alan’s book is really “essential” reading for any arts manager, in any part of the country, at any level of the organization. As discussed above, I don’t think every idea needs to be taken as a commandment or the word of law, if anything, I feel that perhaps the most important aspect of Alan’s book is the fact that it is so radical — and polarizing. If we’re going to tackle as large an issue as the state of nonprofit arts organizations in this country, and the fact that many of them are failing, we’re going to have to be willing to wake up, think outside the box, take some big swings, and perhaps upset a few people. Not everything will work, but at least we will have done something to help not only preserve the American arts nonprofit landscape — which I believe is the greatest producer of art in the world (precisely because of the push-pull with the commercial sphere, discussed above) — but also to help it move forward.

Listen to our full episode here, where we also discuss Jeopardy (Alan is a two-time champ!), regional vs. New York theatre, donor-advised funds, scraping gum off theatre seats, and my dream of seeing a “no-fly” version of Wicked. As always, let me know what you think in the comments, and pre-order Alan’s book now!

Hello,

With respect to 501(c)(3), Michael Rushton wrote an excellent piece which I link below. In essence, you can look beyond the text of the tax code to regulations and rulings published by the IRS, which make it clear that providing exhibitions and performances are per se educational activities, so cultural organizations don’t have to “earn” c3 status by having robust educational arms. I don’t quarrel with the idea that they should have them, or that they should think about impact. Here’s the link: https://www.artsjournal.com/worth/2023/07/producing-and-exhibiting-arts-as-a-nonprofit-entity-is-a-qualified-tax-exempt-activity/ I’m commenting in a purely personal capacity.

Harrison’s premise is wrong, and his conclusions from that premise are at best unproven. Yes, a literal reading of the qualified entities in the 501(c)(3) designation does not include arts organizations. But in practice, several decades of legal precedent does recognize arts organizations whose purpose is to present and preserve art, as educational in a broad sense. A list of several dozen institutional types is described under the “Arts, Culture & Humanities” range of of the National Taxonomy of Exempt Entities Codes, and they include museums, performing arts centers, and any aspect of cultural life that you can think of. Pace Harrison, the production of art *is* a valid charitable mission, whether he personally regards it thus or not. The IRS’s generosity on the topic exceeds Harrison’s, which is saying something. That organizations “don’t even create art; that’s what artists do,” is not a sensible account of the manner in which artists have long worked with the institutions.

There are many organizations, including several criticized by name by Harrison, that had community-facing efforts to solve practical social problems, educational and otherwise, and were nevertheless forced to close in recent years. While Harrison exhorts nonprofit arts leaders to pivot into social justice work or be ruined, the fiscal environment seems to be worsening for everyone. It’s not clear that anyone will be protected by such pivots, and it’s not demonstrated that donors will reward them. The organizations may in fact waste resources they need to survive by investing them in social projects for which the organizations are neither qualified, nor equipped to measure impact.

Thanks for this. Unfortunately Alan is just wrong in his thinking about the role of arts organizations in their communities.