I was so thrilled to be able to bring Jesse Green, Chief Theatre Critic for The New York Times, on the podcast this week to discuss his book Shy: the Alarmingly Outspoken Memoirs of Mary Rodgers. I had Jesse on the previous iteration of the show (when it was called “Theatre Book Club” and done through Berkshire Theatre Group) to discuss his own career, the nature of theatre criticism, and other topics like that back in 2020, but as soon as this book came out, and I then read it myself, I knew I had to have him back on.

Like I say at the top of the podcast episode, the book felt tailor-made for me — and in many ways, for my “Call Time” audience. For anyone reading who might be unfamiliar: Mary Rodgers was the daughter of Richard Rodgers, the composer of Once Upon a Mattress, the writer of Freaky Friday, the former Chairman of the Juilliard School, and the mother of contemporary theatrical composer, Adam Guettel. She was born into the storied world of Old New York and Old Broadway (when composers and lyricists lived at the Carlyle, “orchestra readings” took place in the pit, and lunches were an endless flow of Dubonnet and gin), and she herself came of age during, arguably, the most exciting time on Broadway and in New York: she hob-knobbed, worked with, ate, drank, and socialized with luminary figures like Leonard Bernstein, Bing Crosby, Judy Holliday, Barbra Streisand, Woody Allen, Hal Prince, George Abbott, Irving Berlin, Oscar Hammerstein (or “Ockie” as she called him), Lorenz Hart, Carol Burnett, and, of course, Arthur Laurents (of whom she has several withering comments to make, my favorite being: “Talent excuses almost anything but Arthur Laurents”).

Perhaps most fascinatingly to the reader — at least at first — she maintained a lifelong friendship with giant of the theatre, perhaps greatest musical theatre composer to ever live, Stephen Sondheim, whom, as she describes in the book, she met playing chess at “Ockie’s” farm in Buck’s County (“he beat me fiendishly, took no time at all…Once we ran through that, we went to the piano where he played “Rhapsody in Blue” or “An American in Paris”…I was dazzled by [him]”). Not only were they lifelong pals, as most theatre people knew even before the publishing of Shy, but Mary also inspired a great deal of Sondheim’s early work content-wise (you think of the lyric “Hank and Mary get into town tomorrow” in Company and arguably the entire character of “Mary” in Merrily We Roll Along). Most surprisingly, the book reveals that, at the advice of Sondheim’s psychiatrist at the time, the two engaged in a “trial marriage,” a fact that, when he learned of it, Jesse tells me he “nearly had to be scraped off the floor.”

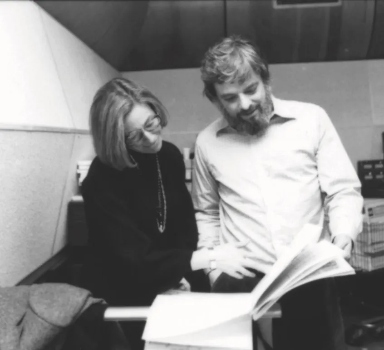

What’s more, every little nugget of theatre gold is delivered to you absolutely deliciously (as you might have gathered from some of the quotes I’ve highlighted above). Indeed, the book is structured such that you have Mary’s voice — cutting, dry, hilarious, the kind of person who, upon reading the first ten pages Jesse had prepared, exhorted him to “make it meaner; make it funnier” (that’s my kind of woman!). Interspersed throughout, in footnote form, you also have a nameless, “other” voice. It becomes clear over the course of the book, as this nameless other “comes out of the closet of the footnotes” (as Mary apparently said), that the voice is Jesse’s. It felt as if this “main text” and the footnotes, in other words, Mary and Jesse, were themselves engaged in a kind of witty repartée. At one point, Mary asserts in the main text that she knew specifically that an LA earthquake occurred on a Wednesday “because I was in my mother’s arms, not the nurse’s, and my mother held me only when Mam’selle, as we called her, had her day off [which was Wednesdays].” “Fine,” Jesse’s footnote asserts, “but the earthquake occurred on a Friday.”

The text goes on a lot like this, weaving in and out of Mary’s voice and Jesse’s, as if they are having a couple of vodka stingers at the best bar in town (I’m going to guess Bemelman’s or Monkey Bar), probably right before or after a trip to Zabar’s for some lox and fresh whitefish, and you just happen to be there too, observing, and laughing into your cup. In that way, the book is, as I tell Jesse on the show, a huge achievement stylistically. Somewhere between biography and novel, Jesse was able to find the sweet spot, upending the form and allowing the 458 page text to feel more like a monologue, or rather a dialogue, than non-fiction.

One of the other huge achievements, as I tell Jesse on the show, is that the book could have stopped there: I would have read a juicy, tell-all portrait of Old Broadway and the cast of characters who inhabited it, doubly so if it was funny. But in addition to making me laugh out loud, Shy also made me cry — and think. This is at least partially because in addition to all of the aspects of Mary’s life that were incredible and filled with friends, family, achievement, and extraordinary privilege, she also faced major challenges. She had an incredibly difficult childhood with her extremely controlling and cold parents, who criticized her for everything from her smile to her laugh, and always about her weight and her body (her father was also reportedly a major alcoholic).

What’s more, Jesse compares the ultra-rich, Jewish, New York City society into which Mary was born to that of a Jane Austen novel, in the sense that there was “terrible pressure on her…before anything else, to get married, [to] find a way to button her life together [in that way].” Jesse explains that this pressure to “marry well,” even coming from a father who himself had forged a brilliant career, “trump[ed] any individual traits or talents that she as a young woman might have.” Indeed, this pressure arguably led to her disastrous — and abusive — first marriage to a closeted gay man. Finally, and most disturbingly, one of Mary’s young children, Matthew, passed away suddenly in the mid-sixties. Of this period of time, Mary writes acutely but sparingly. “People seemed, and have seemed ever since, dissatisfied with my grief,” she/Jesse writes. “For me, grief was too complicated an emotion to have, at least at first. I felt simpler, sharper things, unpredictable stings and slaps, like someone invisible was trying to hurt me.”

Somehow, Mary soldiers on, and maintains the emotional center of her family (she ultimately raised five extremely successful children, with whom she had wonderful relationships, and she had a long-lasting second marriage). She does it, as Mary writes in the book, because she had to. There was no other choice. It’s a quality that I most admire in people, whenever I find it: a willingness, nay, a CALLING, for survival. To live, and shape your own life, your own destiny, no matter the unimaginable loss. As Jesse says to me on the podcast, “[the book]’s about theatre because we’re all interested in theatre, but I don’t think that matters if you read it and you don’t know about theatre. That core of the story about her creating her life the way she needed it to be, imperfect though it was, is broadly relevant.”

And it connects to the parallel Jesse was drawing between the world in which Jane Austen wrote and the space Mary occupied. As Jesse tells me on the podcast, “part of the movement in [Austen] novels is the development of self knowledge in the young women that they need not and or should not sacrifice themselves for the expected marriage.” As I’ve written about before (largely in my college thesis), Austen novels are actually not romance novels, and to categorize them as such is a major misinterpretation. Austen novels are about self-determination, the forging of one’s identity independent from marriage, men, or even one’s family. In this way, Shy is the contemporary answer to the Austen novel: you watch, rapt, as Mary works out problems like: “What is love supposed to be in…life? What is sex supposed to be in…life? What are children supposed to be in…life?”

Indeed, before this book’s release, many people thought of Mary Rodgers, as Jesse tells me on the podcast, as simply the “meat in the sandwich” between her much more famous father and son. One might also add the great love of her life, trial husband, and stalwart friend, Stephen Sondheim, to that list. Mary herself was insistent that she didn’t belong in the “same top drawer” of the “talent chiffonier” as men like her father, son, and Sondheim (by the way, we have barely scratched the surface of the sexism — both subtle and blatant — Mary faced as a female composer on Broadway when that job was seen as almost exclusively male). Ultimately, the question of Mary’s talent and where she “ranks” on the hierarchy of Broadway greats is somewhat irrelevant to Shy, and the kind of book Jesse wrote. As he said when I asked him what he most wanted readers to take away from the book, Jesse explained, “I would like people to be moved and inspired by a woman’s insistence on creating her own life on her own terms.” The rest — the Broadway stories, the descriptions of Old New York, the gossip, the reveals, the intrigue, the sex, and, yes, the talent — is all gravy.

Listen to my whole episode with Jesse Green, one of my favorite discussions I’ve ever had on the podcast, where we delve deeper into the sexism and anti-Semitism Mary faced, the writing and editing process, Christine Baranski’s read of the audio book, Jesse’s “day job,” and so much more. As always, let me know if you enjoy our discussion — or this article.

A fabulous interview with a fabulous guest! Such fun to listen to such bright people discuss such an interesting woman! I am ordering the audio tape as soon as I finish this comment!!! Thank you!