I had the pleasure of returning to the podcast in a pre-recorded segment I filmed with NAACP and Fred Astaire award winning Broadway choreographer, Patti Wilcox. The episode was taped in advance because, for only the second instance in Call Time history, we did the show live and in-person, as Patti and I were staying catty-corner (or perhaps “citty-corner,” as we explore at the top of the podcast) from one another in Paducah Kentucky, putting up the National Tour of Annie. I hope you’ll listen to the full episode — in addition to reading this accompanying article — for many reasons, but one of them being that there’s a certain giddiness and openness to our conversation that I believe speaks both to the pent-up energy we were experiencing (we were speaking right before going into tech) and the nature of an in-person recording. If you like what you hear, let me know, and perhaps I will shift to do more of them…

I also think it has to do with Patti as a person. I met Patti when I was assisting Jenn Thompson on her production of Gypsy at Goodspeed Opera House earlier this year, for which Patti was choreographing. As I mention on the show, creative teams function really differently depending on the production, the theater, and the people (of course), and very often the director is in one room, staging, while the choreographer is in the other, and they only really come together for runs and to “show” one another what they’ve produced. If you are an assistant or associate director, in my experience, you might therefore get to know the choreographer in passing, but there aren’t many opportunities to forge real bonds — you’re not really working “together.”

But things were totally different with Patti. As discussed above, either because of the nature of Goodspeed, Gypsy as a show, or her relationship with Jenn (or all three!), I felt like I really got to know, and forge a distinct bond, with Patti. That was doubly true working on Annie together this fall. I think it speaks to Patti as a person — as you’ll hear on the show, she is incredibly well-spoken, caring, and thoughtful. But it also speaks to how she works and creates as a choreographer.

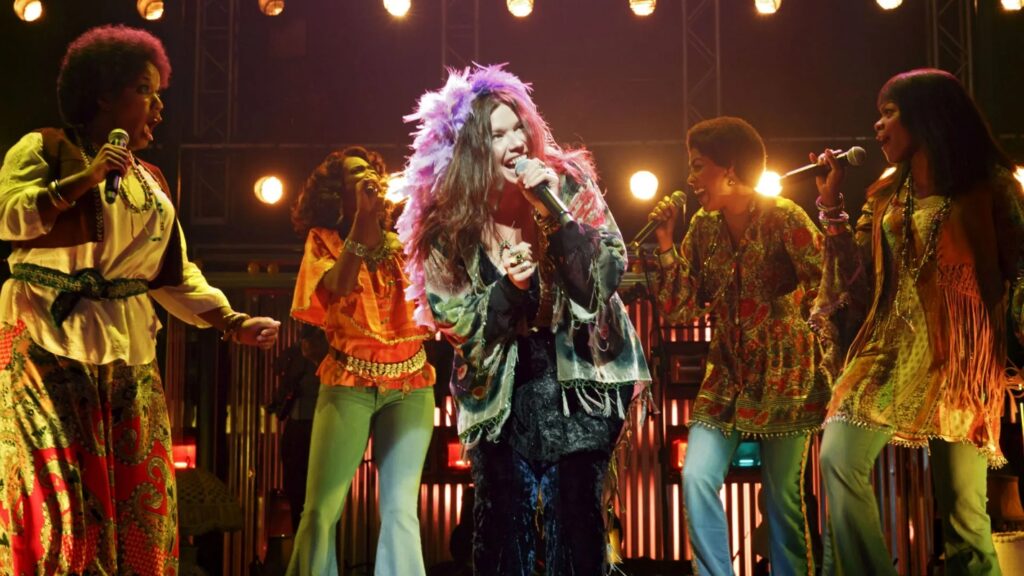

For Patti, “narrative is everything.” “Everybody thinks dancers do steps, [or that] choreographers make steps,” Patti tells me on the podcast, “we don’t do steps. Dancers are storytellers first and foremost.” A lot of dancers and choreographers pay lip service to dance as storytelling, and where it lies on the “hierarchy of expression” (at the highest point, as I’ve written about before), but they don’t actually live it in their artistic practice. Having worked with Patti twice in the last year on two big musicals, I can tell you firsthand that Patti actually lives and breathes it.

Her process speaks to the unique importance Patti places on narrative and how dance can propel a story. Before anything, Patti tells me on the podcast, “[I] become so acquainted with the script and the score…[asking questions like] what is the narrative and why do we sing here and what do the songs mean? So I storyboard that…” When I press her on what she means by storyboard (“talk to me like I’m in kindergarten” I say), she explains that for each and every song in a musical she organizes them into sections, say, A, B, and C, and figures out “what do I have to say here? And what makes me dance here? And then what makes me arc it here? And what either builds it to the next level or how do I finish it in a different way?” In this way, the dance should work in tandem with the music to express the story/characters, often in a way that words cannot.

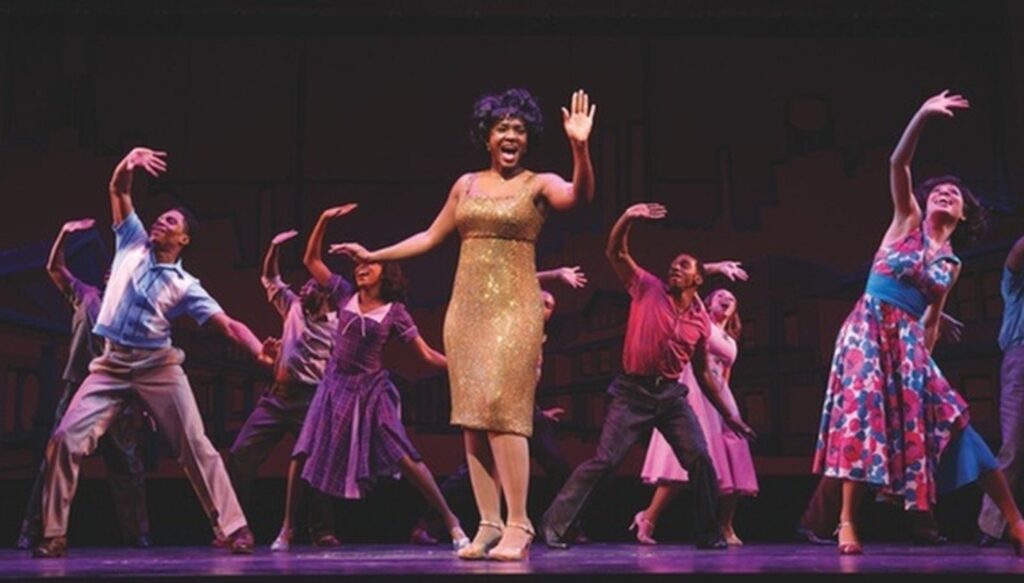

From there, Patti creates on her own, without mirrors. Again — an aspect of her process that distinguishes her from some other choreographers. For Patti, at least in the early stages, the dance is about how it serves the narrative and, therefore, how it feels on/in a body, rather than necessarily how it looks. Of course, at a certain point, Patti brings in an associate, or several other dancers to help, as she puts it, “get it out of my head…get…[it] out of my body and onto people.” Indeed, this step of the process is extra important because, as Patti reminds me, often in a big musical number (not unlike a ballet) every single person onstage is doing a different set of “steps,” and, therefore, telling a slightly different story or playing a slightly different role in the narrative.

You can see this in Patti’s work itself. One thinks of a big musical like, say, Annie, and you might think about classic “chorus numbers,” like “NYC.” But after conducting this interview with Patti, and learning more about her process and how she thinks about/conceptualizes dance onstage, I found myself paying closer attention to what she had created for the show. Watching a number like “Gussie” during tech, I realized that Patti was right: even when everyone was singing together, almost every single person onstage (which was almost our entire cast!) was doing something slightly different, telling a slightly different story about how they felt about Warbucks adopting Annie. Similarly, in the aforementioned “NYC” number, Patti was able to capture the hustle and bustle of Manhattan, and the way that every single person you pass on the street might be going in the same direction, or moving equally fast, but all have different goals, desires, backgrounds, and relationships to the “city that never sleeps.” Patti captured something I loved about musical theatre that I hadn’t even been able to articulate before — that Runyonland esq. devotion to different narratives told through movement (don’t get me started on Runyonland….as a director, I want to put a pseudo-Runyonland sequence in almost everything I do, and someone normally needs to stop me).

Of course, at the end of the day, there are steps to be learned, and choreography to be written down (in my “explain to me like I’m in kindergarten” phase I ask her incredulously how choreography gets passed down because, as a “strong mover” but not a dancer DANCER, I’ve always found it difficult to imagine how one communicates what is largely uncommunicable or unimaginable to me). “That’s why you have a program like Stage Write,” Patti tells me, a software that’s to some extent industry standard allowing choreographers and directors to track spacing, set pieces, props, and light cues using a digital script, and a “great associate” (shout-out to Jessica Blair, Patti’s associate on both Gypsy and Annie, and whom I adore).

“When is a number done?” I ask Patti towards the end of our discussion of process and narrative. “On opening night?” Patti asks, sarcastically. We share a laugh, because we both know, as I say on the show, that “if the creatives had their way, we could go on and on until the end of time, taking notes and redoing things.” “I think you’re always looking at what you could tweak or work,” Patti tells me. “There’s a feeling when it’s right or there’s a feeling when it’s done, and, it’s interesting, even when you take time away from it like we did [with] Annie a year ago, I’m looking at things now going, ‘Oh, I want to tweak that. I want to add this. I want to shape that in a little different way,’ because it’s been a year, because I’m different, because I see it differently, or it’s different people, or I hear something a little differently. And I think that’s what’s interesting about the creative process, is that I don’t know that there’s [necessarily] an end.”

I’ve written about this feeling before, and maybe that means there’s a longer article to be written about the topic, but I believe the concept of endings, or whether the work is “done” or “finished” on a show, is one of the most difficult aspects of being on the creative team. When you’re directing, choreographing, or designing, unlike an actor, whose performance is a living, breathing thing that happens eight times a week, your work has a clear endpoint, one that, as Patti alludes, can often feel false. But, as Patti and I both imply, sometimes you need to take that ending, however false it might appear, and run with it: move on, let it go, let it live and breathe without you, because otherwise, you could be noting, and tweaking, and changing until the end of time. What’s more, if movement is more than steps, you can always be telling the story a little better, a little differently, a little more interestingly. And that drive isn’t about pursuit of perfection, but rather about creative expression. It’s what makes Patti such an interesting, unique, and ever-evolving choreographer.

Please listen to our whole episode here, where we also cover Patti’s stint as a dancer in Italy, show “bibles,” “work/life balance,” the troubling lack of major female choreographers in the industry, Steps on Broadway, and choreographing for Olympic ice skaters and violinists alike. I’m so happy to be back doing the show and writing for Arts Journal — stay tuned for some amazing guests, interviews, and essays coming up. Writing and doing the podcast for you all is truly one of the highlights of my week!

Leave a Reply