This week on the podcast, I was so excited to dip my toe into the world of film with my guest, screenwriter and director (Francophrenia (Or: Don’t Kill Me, I Know Where the Baby Is), Burn Country, and Slow Machine), Paul Felten. As I say at the top of the episode, the podcast has its origins with “Theatre Book Club” (at Berkshire Theatre Group), and I obviously come from a theatre, and specifically musical theatre, background, but as the show has grown, reached a wider audience, and even got connected here at Arts Journal, so the scope has expanded too. I’ve had the opportunity to interview true “DANCER dancers,” like Gaby Diaz, Runako Campbell, Barton Cowperthwaite, and Megan Fairchild, administrators like Donna Walker-Kuhne, Tim McClimon, Jane Whitty, and Lisa Gold, scholars like Ryan Donovan and Jeffrey Carr, and, now, filmmakers like Paul.

But Paul is of course unique, even amongst filmmakers. Perhaps most obviously so because he works almost exclusively in the context of so-called “indie” film. Short for “independent” film, the formal definition of the term refers to a film that is produced outside of the “major film studio system” and distributed by “independent entertainment companies.” In other words, an “indie” is any film that wasn’t made by the major film studios that have been in power roughly since the 1930s (when they replaced the “Edison monopoly”): 20th Century Fox, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM), Paramount Pictures, Columbia Pictures, and Universal Studios. Often, but film scholars are quick to point out not “always,” these films tend to have far lower budgets than those produced by the traditional, studio system (I say on the podcast that I once read that any movie made for less than $1 M “counts” as an indie). Film scholars have a lot more to say about the independent film movement, and whether and to what extent it has a particular or unique “style,” the way it’s influenced the “auteur” movement, the way the Hollywood studios attempted to “co-opt” it by purchasing smaller studios like Sony Pictures Classics, Searchlight Pictures, and Focus Features, the reliance on the film festival model, and the way it’s intersected with global/international cinema, but in our episode Paul is able to share some boots-on-the-ground, contemporary knowledge.

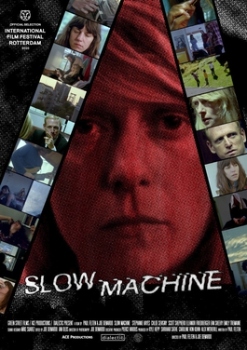

First and foremost, the first round of funding for his most recent film, Slow Machine (co-directed with Joe Denardo), was entirely crowdsourced, using Kickstarter. This is not necessarily unique on the indie scene — the advent of websites like Kickstarter, Pozible, and Tubestart undoubtedly revolutionized indie filmmaking (as did the transition from analog to digital). Second, and on this subject, Paul and Joe filmed in 16 mm, which, he says, adds a “flicker,” a “hum,” and a “warmer quality” that makes the film feel more alive. Clearly, other directors, like Christopher Nolan, would agree (as I say on the podcast, good luck to anyone in New York City trying to see Oppenheimer in 70mm as Nolan intended….nearly all showings in NYC are sold out). Third, and perhaps what makes Paul such a unique window into the film world, and a major reason why I wanted to interview him, it’s very clear in watching his movies how influenced he is by other art forms.

First, the movie is littered with literary references: Blake, the American “ecstatic” poets. On the pod, Paul says he finds books to be a major source of inspiration, and he was, no surprise, an English major in college, studying Shakespeare, Victorian literature, and “American studies.” Second, what I’d call the “indie rock” scene seems to underscore the entire movie — both literally and figuratively. One of the actors in the film is Eleanor Friedberger, the co-lead (along with her brother) of the indie rock band, The Fiery Furnaces, and Paul’s co-director, Joe, is the guitarist for the Brooklyn-based “noise” band, Growing. He, and Growing, did the entire score for the movie, which literally hums with the beat and rhythm of the downtown, Brooklyn, indie, rock music scene. Let’s just say watching this film, and being friends with Paul, is an exercise for me in being the least cool person in the room.

Finally, and perhaps what makes Paul the most unique and a major reason why I wanted to interview him for the podcast, is the way he uses and interacts with theatre and theatricality in his film work. Basically the entire cast of Slow Machine comes from the theatre world (with the major exception of indie film, TV, fashion, and music LEGEND, and a personal idol of mine, Chloe Sevigny): you might know Scott Shepherd from Bridge of Spies or The Last of Us, but he is a giant of the downtown theatre scene, known for countless works with The Wooster Group and as the narrator in Elevator Repair Service’s Gatz; Stephanie Hayes is a Swedish born, Yale School of Drama educated actress who has appeared in works at the Public and with Elevator Repair Service. Indeed, the night Paul met her he discovered that he was seeing her in a Richard Foreman matinee the following day. And in fact, her character — aptly named “Stephanie” — is supposed to be a theatre actress, too, in Slow Machine.

You can feel this veneration, respect for, and curiosity about theatre throughout the film. Paul notes, for example, that he and Joe really tried to give the actors a ton of rehearsal and then a great deal of context for shooting, so that they could feel that the scenes had true beginnings, middles, and ends. “We didn’t shoot endless coverage,” Paul tells me on the podcast, “and we just got the right people in the room and let them do their thing.” “And usually,” he says, “[that meant doing] just three takes.” All of that is extremely rare when working with a camera, especially if you’re working on an indie and filming digitally, Paul tells me. When using film, as they did with Slow Machine, the film is literally too expensive to waste on shot after shot, or “endless coverage.”

The way Paul talks about the Slow Machine process, and the actual experience of watching the film, both indicate that he and Joe took a bunch of amazing theatre actors, and a great deal of theatre conventions, and essentially said to themselves “let’s see what this could look like on camera.” It’s not that a great film is necessarily a “well made play,” Paul tells me, but he likes to think of theatre as a “really important alternative to the orthodoxies of screenwriting class.” “Screenwriting is probably the most aesthetically conservative sort of wing,” Paul explains on the podcast, “I think that the rule in screenwriting is like, ‘whatever works.’ But you can’t charge somebody $80,000 a year to just say that. So you have to give them rules and career advice. And so it can feel a little stifling…and it was nice to be able to go to theatre as an alternative to [those] storytelling orthodoxies.” For Paul, “theatre [is] a great way to see stories told in some of the ways that [are] the most exciting to me…” He cites The Wooster Group, PS122, and the work of Richard Foreman as some of his biggest theatrical influences.

Hearing all of this was music to my ears as a theatre person who is constantly wary of the ways that film and TV have to some extent overtaken theatre as the cultural pastime of choice. It’s not that I don’t love film — I quiz Paul on the first two Godfathers and Broadcast News — but I resent the ways that filmmakers or film people sometimes dismiss the theatre because of its limitations. “With film, you can go anywhere and do anything,” they tend to say, but I’d argue the same is true of theatre, if you let it. In some ways, there’s MORE room for exploration, as Paul implies. I’ve read plays that are just stage directions before (though I’m not sure I’d recommend it) or plays where everyone acknowledges a certain actress as a dog (Sylvia). Theatre can be devised, made collectively by an ensemble that is just essentially doing improv. Whole worlds can be mimed. I believe sometimes film suffers from too much naturalism or too much realism: the curse of the camera, I’d call it, where you can be anywhere and do anything.

As I’ve written before, I believe theatre is best when it not only acknowledges but transcends its limitations (like the famous, opening moment of Hairspray). I’d argue that the same is true of film. Just because you can CGI everything, does it mean you have to? Just because you can, do you have to get the shot from every single angle? Some of the films I’ve most enjoyed play with the form in some way, winking and nodding to the camera that both illuminates and obscures the subject (you think about the films of Jean-Luc Godard, Being John Malkovich, Annie Hall, or, more recently, something like Frances Ha or even Barbie).

This is not to say that film or theatre is better than the other. If anything, I believe that theatre and film directors should both be more like Paul: acknowledging that theatre has a great deal to teach film, and vice-versa. In fact, it’s my belief that there isn’t quite enough healthy exchange between the two genres, as they exist today. If Slow Machine — or even the 2019 Oklahoma! revival which cleverly used filming and a film camera — are any indication, the partnership would be startlingly effective and fruitful.

Please listen to my whole episode with Paul here, where we also discuss David Lynch, country songs about Reno, Nevada, the only acceptable movie snacks, and the greatest TV show of all time, Law and Order: SVU. As always, please like, rate, and subscribe on the podcast platform of your choice — and send me a comment if you like what you hear and read. I am always excited to connect with my audience.

Leave a Reply