This week on the podcast I had the absolute pleasure of chatting with music director, orchestrator, pianist, educator, scholar, and my music director for the show I just directed, The Secret Garden, Jacob Kerzner. As I say at the top of the episode, it was a somewhat unique moment for the podcast because it was my first time interviewing a music director about his life and career for the show, hoping to shed some light on that area of the musical theatre industry.

But Jacob is unique for many reasons. As you can imagine, Jacob is something of a musical prodigy…the kind of person who, as he tells me, realized, at around 20 years old, how many shows required accordion (“it’s shocking how many”) and just picked the instrument up (he’s now quite accomplished at it!). But even for a talented musical person, he is unique for his wide range of talents, and his ability to occupy many different niches or functions within the musical theatre world. In addition to playing the accordion, as discussed, and the piano, Jacob has music directed — at places like Opera Memphis and Berkshire Theatre Group, and for the developmental teams of the 2019 Oklahoma! revival and Hadestown; he’s been a full-time faculty member at East Carolina University’s School of Theatre and Dance; he got his Associate’s degree at Bard College at Simon’s Rock, his BA from Ithaca College, and then went to the Royal Conservatoire of Scotland for his master’s; finally, he is about to move to Ann Arbor, Michigan to continue his work on the first ever critical edition of the George and Ira Gershwin songbook and to serve as an accompanist in the (famous) musical theatre department. It’s clear that he is one of the truest versions of what we call the multi-hyphenate artist, to which I’ve largely dedicated Call Time.

But Jacob is also unique, even among this new generation of multi-hyphenate theatre artists on which I tend to focus, not only because of the truly wide range of jobs he’s occupied, but also because of the places he’s lived as a result. As we discuss on the show, most musical theatre actors and creatives live in New York, and then maybe make a rotation of the same sort of “big 10” regional theaters throughout their careers. During the meet and greets at any one of these shows, you’ll catch actors playing the same “name game” at the Guthrie as they’re playing at Barrington Stage as they’re playing at La Jolla as they’re playing at the MUNY and Chicago Shakes. Even then, actors only live in these other cities and towns for weeks or months at a time, whereas Jacob has lived for at least a year or two in Greenville, North Carolina, Memphis, the Berkshires, upstate New York, Glasgow, and, soon, Ann Arbor, Michigan.

It speaks to the broader crisis the theatre industry — and specifically the regional theatre model — is facing at the moment. There are so many shows lately that I go to see, as I describe on the pod, and I think: they made that for almost exclusively their friends and family within the theatre industry. And while I love that “inside baseball” vibe as much as the next person (see: my “special episode” on [title of show]), I maintain that those shows that rely on “inside” humor have also broken through to the mainstream because they nevertheless appeal to, or at least attempt to reach out to, a broader audience, a new generation of people who might become theatre fans in that one night with that one experience.

Those are the people for whom Jacob says he makes theatre. “I love New York audiences,” he tells me on the podcast, “They are what excite me about a lot of the work that I want to do, but I’ve also found it equally important to build theatre for people in…Alpena, Michigan [where he worked in fall 2019], who have never seen a musical aside from their local community theater. Or [when] I was in Memphis,” Jacob continues, “I was working on opera, and a lot of our mission at Opera Memphis was to give people their first experience of opera. And that could be… provid[ing] free tickets to veteran families…so that they could come into the theatre and experience that. But also we wandered around Memphis with my accordion and a singer [and]…we surprised people with opera…And I think that’s what’s equally exciting about theatre for me is finding ways to integrate it into areas that aren’t so saturated as New York.”

This subject gets into all sorts of thorny topics like audience, programming, community engagement, populism, and whether the American regional theatre model, as it currently exists, even “works.” And what does it mean to “work”? Those are all subjects for longer (upcoming) articles, but I would argue that my conversation with Jacob, as well as his experiences making theatre all over the world aimed at very different audiences, seems to prove that there is, almost universally, something of a disconnect in the theatre right now. And I mean that in terms of the disconnect I describe above — between the artists/producers and the patrons — and even, as Jacob describes, between the schools who prepare future artists and the industry itself. “I think a lot of the conversations in higher education are around modeling the education, modeling the curriculum, around the professional world,” Jacob tells me on the podcast, “And I believe that we actually need to be doing the opposite. We need to be asking questions like: How can we be building the theater we want to exist in our educational circles, as opposed to modeling the educational circles off of the industry?” That disconnect Jacob sees in the theatre education world speaks to some broader choices theatre — and specifically musical theatre — schools need to be making about their philosophies and curricula: are they, for all intents and purposes, “trade schools,” only meant to prepare its students for booking and keeping work, or are they fundamentally “scholarly,” interested in the exploration of what it means to be a theatre or musical theatre artist, and how that genre is evolving?

These questions lead to a third fundamental “disconnect” Jacob and I discuss on the podcast. When we get around to exploring questions about higher ed, I ask Jacob if he’s ever experienced the “second class” status that musical theatre often receives in scholarly, educational, and even real-world settings when compared to “straight” theatre or even opera. I believe I’ve talked about this very issue on the podcast before: it’s the sneering theatre student who focuses exclusively on Brecht but would never dream of studying a Frank Loesser musical. It’s the opera singer or administrator, as Jacob says, who obsequiously assures everyone, “Sweeney is basically an opera,” and therefore worthy of enjoyment and programming.

On the podcast, Jacob refers me to a book by Adam Lenson called Breaking Into Song: Why You Shouldn’t Hate Musicals, which compares the status of musical theatre in the performing arts world to the graphic novel in the fiction/writing world, arguing that any time two, distinct art forms are combined, the public somehow sees the product as “less than” (an insane postulation when you remember Wagner’s theory of “gesamtkunstwerk”). I would argue that you can take this theory one step further — into the economic sphere.

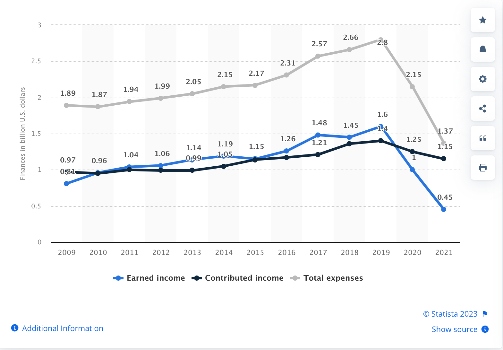

In the United States, theatre, in fact mostly musical theatre, combines two distinct economic forms — the non-profit model and the commercial model. Unfortunately, there aren’t any “commercial” symphonies in modern America; no commercial opera companies; and certainly no commercial ballet companies, or even many commercial dance companies. That leaves theatre, specifically musical theatre, in the sort of “in between.” Yes, plays come to Broadway, and some of them even make money, but more often than not they are produced by the few non-profit theatre companies that have Broadway houses (Roundabout, Second Stage, Manhattan Theatre Club, and Lincoln Center Theater). Most people know that if you want a big, fat, Broadway hit — that will make a lot of money and run indefinitely — you want a musical. So once again there’s this disconnect, contrast, dichotomy, whatever you want to call it within musical theatre: it’s a genre that occupies that penumbra between the commercial and the not-for-profit, between populism and intellectualism, between capitalism and high art. I would argue that all of the disconnects/challenges we discussed above — the disparity between the artists and the patrons, the chasm between education and the industry — are rooted in this fundamental tension within the genre, one for which I don’t have an easy solution. But maybe Andy Warhol did?

In all seriousness, perhaps Andy Warhol (or rather our conception of Andy Warhol) IS the solution. Maybe we as an industry need to stop fighting these tensions and recognize that they are what make musical theatre as a genre one of the most fascinating, interesting, challenging, fun, and evolving art forms in the world: worthy of study, celebration, and, yes, investment. It’s also part of what makes it one of the few fundamentally American arts. Just as Warhol famously embraced the “relation between cultural production and capitalism,” perhaps everyone involved in musical theatre needs to do the same. Is it possible to make high art that appeals to a broad spectrum of people and makes a lot of money? I’d argue yes, and musical theatre — as well as pop art — are the proof.

Listen to my full episode with Jacob here, where we do a lot more than wax poetic about the relationship between musical theatre and consumerism (also on the docket: imposter syndrome, Brexit, unions, straight tone to vibrato, and the Gershwins). As always, like, rate, and subscribe to the show on Apple, Spotify, or wherever you enjoy podcasts, and throw me a comment if you have thoughts on the article! Until next week!

Leave a Reply