I am so glad to be back with Call Time and with Arts Journal. As I say at the beginning of the podcast — and as I mentioned in my last episode back in March — I had to take some time off while I was assistant directing Gypsy at Goodspeed Opera House and finishing my graduate degree at NYU. I imagine this time away from the show will only prove useful — I learned so many new things, and made connections with so many new, incredible artists, that my lineup of shows, guests, and articles coming up is truly one you’ll want to watch.

For now, I have my NYU network to thank for my guest this week. I had the pleasure of interviewing former Senior Vice President of Corporate Social Responsibility at American Express, former Executive Director of Second Stage Theater, current Executive Director of Signature Theatre, and one of my favorite NYU professors, Timothy J. McClimon. Interviewing the Executive Director of a big-time, NYC, non-profit arts organization is a first for the show, and a step that feels particularly relevant to my own career and, as the title of the article implies, this particular moment in the broader theatrical sector.

I talked with Tim about his own career trajectory: how he got interested in arts administration when he found himself running the student union “coffee house” at his small, liberal arts college in Iowa; how this “gig” turned into running a yearly rodeo (among other events) at Western Illinois University; how he attended Georgetown Law at night and then practiced at (then named) Webster and Sheffield; how his mentor tapped him to do corporate social responsibility first at AT&T and then at American Express; and how after years of being an arts patron and supporter (even serving on various Boards), he’s now had the opportunity to act as Executive Director at Second Stage and now at Signature Theatre. We discuss different kinds of careers — the old-fashioned staying at one place model, and one that clearly Tim has fallen into, where, as he described it, he “just said yes to things and seized opportunities as they came.” We even discuss his favorite eateries near Signature (catch Tim, among other “theatre people,” at Marseilles, Molivo’s, or Chez Josephine in midtown). But, most importantly and interestingly, Tim and I have a long — and frank — discussion of the current economic and artistic climate in the sector, from the perspective of an expert.

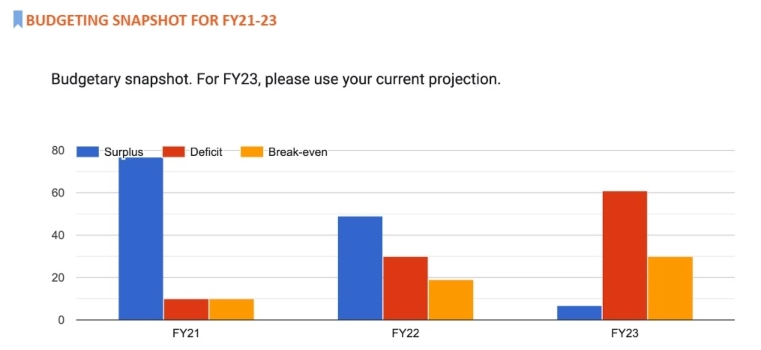

It’s no secret that the nonprofit arts landscape is not doing well at the moment. While in many cases Broadway, and other commercial, theatrical ventures have “bounced back,” smaller, nonprofit theatres (as well as dance companies, opera companies, and orchestras) have continued to struggle. Government pandemic relief packages have largely dried up. The Metropolitan Opera was forced to dip into its endowment. The experimental, downtown New Ohio Theatre closed. Pillars of the regional theatre scene like Williamstown Theatre Festival have been forced to do pared-down seasons, filled with readings, cabarets, and co-productions. SMU DataArts reported that, in 2023, a majority of surveyed arts nonprofits projected massive deficits. And young people across industries have demanded major changes in workplace culture and work/life balance. As someone shaping a professional career in the theatre, these kinds of developments are really scary: especially when, as I see it, voices in the industry fluctuate between absolute alarm (“nothing will ever be the same again and hundreds more theatres will shutter their doors”) and silence (“everything’s great; what are you talking about; we’re just doing fewer shows”…hmmm). In that way, it was illuminating, interesting, and, honestly, comforting to have a frank conversation about the state of the industry with someone who really knows — like Tim.

First of all, Tim is very clear that audiences are not coming back to the theatre (at least to Off-Broadway plays) in the same way that they did pre-pandemic, and those numbers aren’t expected to rise anytime soon. He connects this trend not only to an aging audience but also to “competition with the couch,” which intensified during COVID lockdowns, and, relatedly, the impact of remote work. In fact, Tim tells me that Signature’s found that its most popular days of the week with audiences are Tuesdays and Wednesdays — which happen to correlate with the two days with the highest occupancy rate in New York City offices. I ask Tim if, therefore, a nonprofit theatre needs to rely on a magical alchemy of smart programming and smart branding to bring audiences back in. He acknowledges that, of course, everything starts with programming, but that at a small, nonprofit theatre like Signature, which is committed to small houses and affordable ticket prices, earned income is never going to be in the same ballpark as those for Broadway or musical productions (where you can charge 1000 people $199 per ticket).

So that leaves us with contributed revenue, I concluded on the podcast (for those who are unfamiliar, that’s funding coming from corporate sponsors, private foundations, government grants, and generous, individual donors). Tim extolls the contribution of private foundations, but, he acknowledges, like most nonprofit arts organizations, the role of government is essentially negligible (separate article or podcast coming about why that’s such a shame…my NYU thesis dealt with this topic). This whole discussion and line of thinking therefore left me with one big, blaring thought: So where are all the individual donors, or, as Cuba Gooding Jr.’s Jerry Maguire character might say, “SHOW ME THE MONEY!”

“If I knew the answer to that, I’d sleep better at night,” Tim tells me on the podcast. But I don’t mean to be glib about this very real issue. If a small, nonprofit theatre is committed to affordable prices and intimate spaces, and the government is unwilling or unable to provide much financial cushion, the only means of generating enough revenue to cover expenses and survive for these theatres is the support of individual donors. Tim explains that, yes, the competition for wealthy donors is fierce in the city, and that many of them seek Board seats or involvement with organizations that are thought to be more “prestigious,” like the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the MoMa, the Metropolitan Opera, the New York Philharmonic, or the New York City Ballet. It’s hard for a small, Off-Broadway theatre that’s committed to producing the work of new playwrights, often unknowns, to compete with those kinds of names and histories. But even at these storied organizations, with more money, more resources, and more general “glamor,” I’ve heard that attracting wealthy NY individuals — especially younger ones — is difficult. And I’m not even talking about twenty somethings or even thirty somethings: industry-wide, there seems to be a struggle to attract donors and Board members on the forty-something end of the spectrum. As I ask on the podcast: “Where are all the hedge fund people? Where are the private equity guys?”

While supporting other causes (like poverty, education, medicine, and the environment) is completely and totally admirable, Tim admits on the podcast that “we haven’t done a good job as an industry in attracting these younger people.” I don’t know if that means more “young members” nights, more parties, more lectures and talkbacks, or even more articles like this, but something has gotta give, and something has to set these institutions up for the future.

For now, given that the initiatives meant to course correct the industry and its relationship to young people are “long game,” as Tim describes, he is focused on doing what’s necessary in the short term to survive: in this case it’s a simple formula of raising/earning more money and cutting expenses. In fact, Tim tells me on the podcast that he’s been able to cut Signature’s deficit this year by 2/3 from what it was projected. I imagine a lot of that has to do with Tim’s smarts, flexibility, and determination, but also his willingness — and desire — to look at the finances and management of an organization with fresh eyes. “My biggest pet peeve is ‘this is the way we’ve always done things,'” Tim tells me on the podcast. “I think that’s a death knell for organizations. Unless the way that you’ve done it, you have evidence that it’s really the best way of doing things…but often that’s just used as an excuse for not thinking about doing things differently. Or it’s a roadblock that’s put up by people. So it…really gets my goat when people say that. I’m not very tolerant in those situations and will automatically think that we should do it differently if somebody says that.”

This kind of thinking speaks to Tim’s abilities as a self-described “transitional” or “builder” CEO. “I like building organizations,” Tim tells me on the podcast. “Once an organization is completely stable and secure…it’s not as challenging or interesting to me.” It’s why he was such a good choice for Second Stage when they were moving to midtown, and why he’s such a good leader for Signature at this particular moment. It’s also why, after having this very intense conversation about the state of the sector post-COVID, Tim was able to say that he’s “cautiously optimistic” about the business. “We will find a way not only to survive, but to grow,” he told me. “Because I think we have good product and good relationships and a good facility and good people. I think that we’ve got the right ingredients. We just have to make them work better.” Tim argues that this finessing of ingredients not only lends itself to but will REQUIRE the involvement of new voices — and younger, more diverse voices. “There’s a lot of room for new ideas,” he says. “There’s a lot of room for more diversity in organizations. There’s certainly a lot of need for younger people to lead these institutions. And so I just think there’s a lot of opportunity for people to come in and make a real difference…” In a way, based on what Tim’s saying and his knowledge both of the arts landscape and of leadership in general, the scariness and uncertainty of this moment in theatrical history could make it easier for a new, and more diverse, generation of talent and leadership to take the reins, and even give us the ability to make a far greater impact than we normally could at this stage of our professional careers. And isn’t that what my whole show is about: how a new a generation of multi-hyphenate artists can reshape not only their own careers and identities in the theatre but the industry itself?

I am so happy to be back to the show and back to Arts Journal, and I couldn’t have imagined a better discussion to bring us all back together. Please be sure to listen to my whole conversation with Timothy J. McClimon, where we also discuss his professional mantra (“focused but flexible”), being facilities rich but resource poor, the relationship between artistic and executive directors, papering, the role of a nonprofit Board, The Merchant of Venice, only children, and much, much more.

Leave a Reply