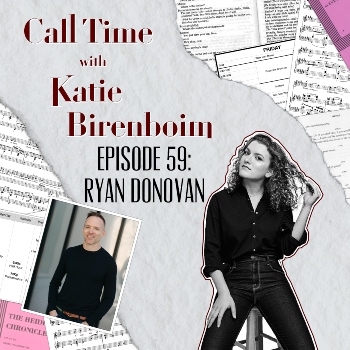

In a first for this iteration of Call Time with Katie Birenboim, I was so excited to welcome a theatre academic — assistant professor of Theatre Studies at Duke University, Ryan Donovan — to the show this week. As we discuss on the podcast, Ryan initially came from the performance world: he was a dancer for many years, performing in shows like the 50th anniversary tour of West Side Story and at the best of the best regional theaters like Goodspeed Opera House and Theatre Under the Stars, before deciding to get his PhD and pursue a career in academia, studying the kinds of musicals in which he had performed. Not only that, but Ryan wrote a book (an expansion of his dissertation), published by Oxford University Press, that will become available to the public on February 10th, and on which we got to have a wonderful discussion. Many firsts for the podcast, my Arts Journal platform, and both guest and host.

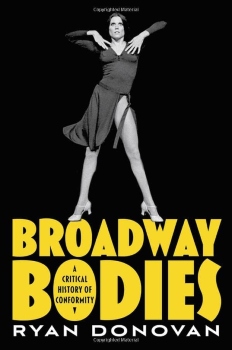

Ryan’s book, entitled Broadway Bodies: A Critical History of Conformity, focuses on the relationship between body politics and the casting of Broadway musicals. He uses three musicals from 1970 to 2020 as kinds of “case studies” in how people with bodies that somehow don’t conform to the “mainstream” are cast, and then treated, on Broadway: in his discussion of Dreamgirls, the 1981 Michael Bennett musical, Ryan focuses on the treatment of “fatness” on Broadway — especially when that identity intersects with others like race and gender; in his discussion of sexuality — and how sexuality can or can’t manifest onstage — Ryan focuses on the 1973 Jerry Herman musical La Cage Aux Folles; and for his discussion of the ways that ability and disability are treated, cast, and written about onstage, Ryan focuses on the 2015 Deaf West production of Spring Awakening. Ryan uses A Chorus Line — in many ways the ultimate “casting” musical, as we heard last week, that set the blueprint for how people of different ethnicities, classes, sexualities, and body types might appear onstage — to frame all of these discussions. And of course, because he is an expert in the field, Ryan peppers other relevant musicals throughout. Think: Hairspray, Shrek, The Music Man, The Tap Dance Kid, The Life, Big River, Jagged Little Pill, The Light in the Piazza, The Secret Garden, Violet, the list goes on.

So if you’re a major theatre nerd, like me, you will definitely enjoy the book. But you will also find it to be thought-provoking and interesting. Broadway has — rightfully so — had a number of long-awaited discussions about equity onstage and what that means, particularly during the pandemic and after the murder of George Floyd. As Ryan and I discuss on the podcast, in many ways, the theatre industry is responding to these discussions positively: the ensembles of most musicals running today look extremely different from how they looked even, say, five years ago, and it’s exciting to see shows like A Strange Loop enjoy mainstream, commercial runs on Broadway (we can leave discussions of what it looks like “behind the table” for another time…there’s clearly a lot of work yet to be done).

Nevertheless, Ryan’s book addresses people — and bodies — that aren’t often included in these calls for equity. You read with horror as you discover that actresses playing Tracy Turnblad in Hairspray endured weigh-ins and were fed milkshakes and chocolate bars immediately after shows or workouts in order to ensure that they had the stamina for such a highly aerobic run while maintaining the “pluz-sized” body for which the show was famous (and without which the plot simply wouldn’t make sense). You’ll remember how often disability is actually represented onstage — Clara in The Light in the Piazza, Winthrop in The Music Man, Violet in Violet, the “phantom” in The Phantom of the Opera! — and how often those characters are imbued with some kind of other, extraordinary ability, as if to compensate, and played, to much acclaim, by non-disabled actors.

You’re forced to consider issues of visibility — as Ryan says on the podcast, “when I was showing early drafts to other academics for peer reviews, no one questioned the words ‘fat’ or ‘disabled,’ but they did question definitions of ‘queer.'” Does the theatre industry bear a responsibility to cast queer people in queer roles, despite the fact that it’s a “fluid,” and less “visible,” identity? Finally, you’ll consider how an identity that Ryan explores, like “fat,” might interact with others that could make an actor’s experience on Broadway particularly turbulent, as it did in the case for Jennifer Holliday, who was made famous for her star-turn as Effie in Dreamgirls, but dealt with racism, sexism, and body-shaming at the same time.

I asked Ryan what he, as someone who has devoted years of his life to researching casting practices and how they interact with body politics, would say to the common rejoinder that the “best” people should always win the role. Or, another common one: “it’s called ACTING.” The implication, there, being that a good actor should be able to play anything — whether it be “queer,” “fat,” or “disabled.” In fact, as I allude earlier in the piece, there’s this trope that playing any of these types of roles, especially as a straight, cis, het, white man, will win you accolades (there’s evidence of this: think about Tom Hanks in Philadelphia, Sean Penn in Milk, Daniel Day Lewis in My Left Foot, even Brendan Fraser in The Whale this Oscar cycle). Ryan’s answer was really interesting: “The way I think about it is that in an ideal world, all casting would be flexible and everybody could play everything because, sure, it is called acting,” he said. “And yet, that’s not the world that we inhabit…People are routinely denied opportunities because they are disabled, because they, you know, quote unquote ‘sound gay.’ Or ‘you need to butch it up,’ [which] I was told so many times at dance auditions…the choreographer would say that to the whole room.” “People are denied roles because of the size of their body,” he went on to explain, “And so, you know, we’re still really thick in that place right now, and until we get out of that, I think that we do have to address casting…from a point of equity.”

Ryan uses Marcia Milgrom Dodge’s production of Beauty and the Beast, which ran at the Olney Theatre Center this past winter, as an example of what that kind of casting can look like. Dodge cast Evan Ruggiero, a performer who lost a leg to cancer as a young adult, as the Beast/prince and Jade Jones, a self-described “queer, plus-sized Black woman,” as Belle. While the show garnered a great deal of national attention for these casting choices, Ryan, who saw the production in person, said that it never felt like a response to a climate of political correctness. “The audience goes with it,” Ryan explained, “because we’re there to be entertained, to be moved, to be told a story.” Why can’t performers demonstrate and experience “the full range of humanity that is not always on offer to them?” he wondered. In other words, why can’t anyone, of any size, ethnicity, sexuality, or ability play Belle, if anyone can play — and has played, often to acclaim — the Phantom, Violet, or Albin?

And that’s another thing I loved about Ryan’s book. He makes all of these (very valid) criticisms of the industry and how it’s functioned in the past, but they so clearly comes from a place of love for the craft, for the people, and, yes, even for the business. It’s rare that I can find that kind of love, and passion, for the industry in academic, and even critical, writing.

It’s another reason why I was particularly interested in having someone like Ryan on the show. I asked him, toward the end of our discussion, whether he feels like an “outsider looking in” now that he’s writing about performance rather than doing it. It’s a question I’ve struggled with a lot as I’ve made pivots, and worn many different hats, in the industry. Does writing about, or studying, theatre mean that I love it any less? Or, more chillingly, does evaluating, studying, or even working in theatre management mean that I can’t foster the same kind of special, close connections with the theatre people I love and admire? And finally, does writing about theatre effectively wash your hands of it — you’re no longer down in the muck like the rest of us, trying to make the thing? While I haven’t come to hard-and-fast rules on the subject (surely evaluating theatre for The NY Times is different from, say, working in marketing at a theatre company), I do know that these feelings have informed some of my professional choices: I want to be down in the muck with the special, joyful, nobody-else-like-them theatre people; I wanting to be making the things, not just evaluating them. It’s clear that, while Ryan does a great deal of analysis, his book is able to straddle that line of love and study, inside and outside, one that other scholars and critics have no doubt found difficult to transcend.

Please read Ryan’s book, available on February 10th, and listen to our whole episode, for a more complete discussion of body politics, identity, and authentic casting, as well as topics like “crowd work” in shows, Wagner’s Gesamtkunstwerk, the writing of casting breakdowns, the great Stacy Wolf, and more. And please let me know in the comments if you have thoughts on the question of outsider/insider status in theatre. Do you as an audience member ever struggle with this question?

Leave a Reply